Ord Om ordet

Langfredag

Jes 52:13-53:12: Se, min tjener vil nå store høyder.

Heb 4:14-16; 5:7-9: La oss ha tillit til hans miskunn.

Jn 18:1-19:42: Pilots lot skrive en plakat, som ble slått på korset.

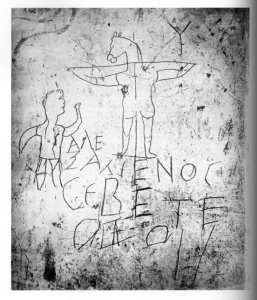

Såvidt vi vet, er tidligste visuelle fremstilling av korsfestelsen en inskripsjon skåret i gips som ble funnet nær Palatinerhøyden i Roma. Vi vet ikke nøyaktig når den ble til, men det kan ha vært så tidlig som i første halvdel av annet århundre, mens det ennå fantes kristne i Roma som hadde hørt apostlene Peter og Paulus preke. Inskripsjonen viser en mannekropp med eselhode festet til et kors. Oppe i høyre hjørne finnes der et Y-formet tau-kors av slaget Frans av Assisi var så glad i. Til venstre står en mann kledd som soldat med én hånd hevet til hyllest. Innskriften, skrevet på omtrentlig gresk, lyder: ‘Alexamenos tilber gud’. Bildet er en karikatur. Det vil latterliggjøre den tilbedende. Vitsen er tidløs. ‘Tilber han en korsfestet mann? Det kan du ikke mene. For et asen!’ Det sies i blant at vi i vår tid, for å skjønne hva korset stod for i antikken, må tenke oss en galge eller en elektrisk stol. Det mener jeg er altfor tamt. Galgen og stolen ble funnet opp som humane henrettelsesmetoder. Korset var tenkt å forårsake så mye pine som mulig. Døden på et kors var uryddig og ydmykende. Alexamenos fremstilles ikke bare som dum, men som pervers.

I dag står dere og jeg ved Alexamenos’ side. Vi bøyer oss dypt foran korset. Vi er ikke blinde for vanæren det står for; men vi ser gjennom den. Vi skimter en veldigere sannhet. ‘Ingen har større kjærlighet enn den som setter livet til for sine venner’ (Joh 15.13). Korset er emblemet på slik kjærlighet. Vennene er vi.

I lidelseshistorien hører vi folk rope, ‘Korsfest ham!’ De vil bli av med ham. De har fått nok. Det var artig å høre ham en stund. Pent var det jo, det han sa; karisma hadde han. Men han fordret urimelig innsats uten håndfast vinning. Da heller Barabbas, den revolusjonære med strategisk plan, en visjon for et omformet samfunn med større frihet, mindre skatt, løfter man blir klok av! Denne andre — Davids sønn, Guds sønn, hva spiller vel dét for noen rolle? — få ham bare bort, få ham endelig til å tie helt stille.

I stillhet led han, utholdt han, døde han. I stillhet betrakter vi ham nå. Men stillheten er ikke taus. Den taler, roper! Den bærer budskap om en kjærlighet som har beseiret verden, besverget døden. Denne kjærligheten lar seg ikke stanse. Den er definitiv, beviselig absolutt. For jo, her på korset tilber vi Gud. Selv i klarsynt møte med hans ydmykelse, holder vi oss ranke. Dét som i dag synes slutten, er begynnelsen på alt. Helvetet bever. Døden rakner. Det demrer i øst. Ved Herrens død, det fullbragte offer, er udødelig håp oss gitt. Et håp som bærer — alt.