Words on the Word

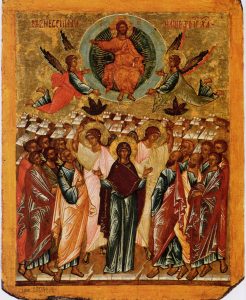

Ascension

Acts 1:1-11: A cloud took him from their sight.

Ephesians 1:17-23: May he enlighten the eyes of your mind.

Matthew 28:16-20: I am with you always.

Almost 47 years have passed since man first landed on the moon. In mid-afternoon on 16 July 1969 a spacecraft named Apollo 11 was launched from the Kennedy Space Centre, entering earth’s orbit after twelve minutes. Three days later Apollo 11 passed behind the Moon and entered the lunar orbit. On 21 July, at around the time when Cistercians rise for Vigils, the astronomer Neil Armstrong opened the spacecraft’s door and set foot, the first man in history to do so, on the surface of the moon.

In a thoughtful phrase, he remarked that his small step was ‘a giant leap for mankind’. The mission, which has left its mark on our consciousness, was a glorious triumph of science. For our theological imagination, however, it was a disaster. It especially confused our notions of the feast we keep today. ‘Now, as he blessed them he withdrew from them and was carried up to heaven.’ For us who live in the wake of the 1969 lunar mission, it is almost impossible to read those words without seeing before our mind’s eye the image of the Apollo rocket fired off from Camp Kennedy.

If we stay within the logic of the image, we are faced with massive conundrums. If Christ took off from earth in that sort of way, where did he go? Is heaven a place out there beyond the galaxies, a place we might reach by our own endeavours one day, given adequate technical know-how? Or was Jesus transported straight to the Father’s bosom? If so, divine realities being immaterial, was he transformed from a person with a body to a purely spiritual being in mid-air? You may sneer at these rhetorical questions. You may think I’m trying to be funny. I am not. Too often have I seen and heard the Ascension represented on the basis of like assumptions. Thereby the feast evokes associations that are plainly absurd. I dare say that is why many people, good Catholics, do not know what to think about the Ascension. It seems too much like a cartoon solemnity, a feast one can’t take seriously, an occasion when faith requires more than is really reasonable.

In the light of this, we had better look closely at the evidence. We are well placed to do so. Uniquely, Scripture gives us two accounts of the event by the same author. St Luke tells us he was not himself an eyewitness to the life of Christ, but he carefully interviewed eyewitnesses. He collated their testimonies authoritatively in a clear narrative that grew in subtlety as, little by little, he came to understand his sources better. The account I just cited (‘as he blessed them he was carried up to heaven’) comes from his earliest text, his Gospel.

It is interesting to compare it with his later account in that Gospel’s sequel, the Acts of the Apostles. We heard the passage read as today’s First Reading. There we were told that, with the Apostles looking on, Jesus ‘was lifted up, and a cloud took him out of their sight’. No longer is it suggested that the Lord shot into the firmament. No, ‘a cloud took him’. In the Bible, a cloud is not just something to do with the weather. When Israel walked out of Egypt, ‘the Lord went before them by day in a pillar of cloud’. The cloud was a sign that God went with them. In it, God’s glory appeared. When Moses scaled Sinai to stand before the Lord, the Lord descended in a cloud. It was likewise in a cloud that, later, he filled the tent of meeting with his presence. In Numbers, the fourth Book of Moses, the cloud has become an established symbol of God’s nearness. This connection is ratified in the historical books. What happens when the temple in Jerusalem is finished, the building work all done? What makes a mere massive building into a sanctuary? At the moment of dedication, ‘a cloud filled the house of the Lord, so that the ministers could not stand to minister because of the cloud; for the glory of the Lord filled the house’.

The cloud is glory. The glory is presence. It tells us that the Lord, the Father of all, is there.

If we read the Ascension story in this context, it no longer leaves us perplexed. On the contrary, the conclusion of Christ’s earthly ministry is found to be continuous with a long history of God’s self-revelation. It is a moment of epiphany. In terms of Christ’s own career, the Ascension cloud recalls the cloud that covered the Mount of Transfiguration, from which, Luke tells us, the Father’s voice announced, ‘This is my beloved Son’. It also points forward to the Lord’s definitive coming at the end of time. Again, Luke gives us the very words of Jesus. Speaking of tribulations to come, he assures the disciples that they will eventually see ‘the Son of Man coming in a cloud with power and great glory’. The cloud will announce that the fullness of time is at hand. Do you see? On Ascension Day, Christ does not disappear beyond earth’s orbit. He enters the glory of the Father whereof the earth is full (Isaiah 6.3). He effectively fulfils his promise not to leave us orphans.

To apprehend this new mode of Jesus’s presence among us, special grace is called for. We need the Consoler, the Caller-to-mind, who will be our source of strength. Christ promises to send him ‘soon’. Throughout Eastertide we have verified that what he says is sure. This word, too, will be fulfilled. Like the apostles, then, let us savour Christ’s Ascension ‘full of joy’, waiting with eager expectation for the Father’s promise at Pentecost.