Queen of the Night

I gather there’s a plan to reboot Amadeus on Sky. Good luck to them. I’ve never understood why people bother to tamper with artistic creations that, within their idiom, achieve something close to perfection – like ridiculously remaking Brideshead. The producer’s promise of ‘a corrupting symphony of jealousy, ambition and genius’ is quite enough to make me resolve not to see the film. Mozart will forever remain a mystery unfathomable. The truest thing that can be said about him is what Piotr Anderszewski says in Monsaingeon’s portrait: ‘I have never been able to reconcile myself to the premature death of Mozart.’ Yet there’s something about the Miloš/Shaffer Amadeus that comes across as definitive. I love this scene in which a telling-off from a fierce mother-in-law makes Mozart touch the essence of one of opera’s most original characters. He must have operated a bit like that. If we were to discover just a fragment of his secret of sensation, how interesting, how rich life would be.

Blindness & Sight

The trajectory traced by St Teresa of Ávila reaches from the outset right to the loftiest end of spiritual life. She counsels souls who wobble ‘like hens, with feet tied together’ but also those who soar like eagles. Nor does she forget the perplexing darkness of the long intermediate stage when the soul, like a timid dove, is dazzled by rare glimpses of God’s Sun while, ‘when looking at itself, its eyes are blinded by clay. The little dove is blind’. Everything she writes, she tells us, is born of experience. For long years she herself ‘had neither any joy in God nor pleasure in the world’. She lived in an in-between state, a no-woman’s land. What changed it? No summary can do justice to her subtle account of the transformative miracle wrought in her by God. We can, though, get some sense of its impact. Teresa testifies how, at a decisive juncture, ‘todos los que me conocían veían claro estar otra mi alma’: her soul had become other; it was no longer what it used to be.

Vince malum in bono

This was the motto of Bishop Jurgis Matulaitis, a great confessor of the twentieth century. A man of learning and deep prayer, he loved the Church and poured himself out for her. He also loved his Lithuanian nation, which he sought to build up by nurturing, after centuries of Russian dominance, its specific national genius and its cultural and ethnic diversity. Bishop Matulaitis was a wise director of souls, not afraid to call a spade a spade. Here is an excerpt from a letter written in 1913 to a man wanting to become a priest: ‘It seems to me that your doubts stem from the fact that your life is much too dominated by self; your life revolves about your person as on an axis. You would like to put yourself and your life into a kind of bank so that your ego might realise as much interest as possible. You would like to protect and insure yourself well so that your ego would not perish or meet with an accident. But even the most cautious of men are sometimes unable to protect their wealth.’ Bishop Matulaitis was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1987. You can find a wealth of resources, including his spiritual journal, on this site.

The Woods

Writes Helen Waddell about Boethius:

‘It was fortunate for the sanity of the Middle Ages that the man who taught them so much of their philosophy was of a temperament so humane and so serene; that the ‘mightiest observer of mighty things’, who defined eternity with an exulting plenitude that no man has approached before or since, had gone to gather violets in a spring wood, and watched with a sore heart a bird in a cage that caught a glimpse of waving trees, and now grieved its heart out, scattering its seed with small impotent claws’:

Interesting After All

Any writer hopes to interest his readers, not necessarily to convince them, but to make them reflect, and to count the time well spent. So I was happy to discover Harry Readhead’s recent review of Chastity. He writes: ‘Chastity is a curious little book. It is immensely readable, yet deals with something I never thought I would find remotely interesting. It reconsiders and reframes a virtue that has long been understood simplistically and scornfully. By the time the curtain, as it were, comes down, we have the impression that chastity, in its broadest definition, communicates something noble, something admirable, something freeing and — ironically — something desirable. We are, in other words, persuaded by the author’s argument, which is subtle but insistent, clothed in the language of reflection and meditation: for it is an argument for a life lived on our own terms, liberated by the racket and noise of ego.’

Guardian Angels

The beginning of Newman’s poem The Dream of Gerontius speaks of a marvellous encounter. Just as Gerontius leaves this world, he realises he is not alone. A mysterious, discreet companion accompanies him into the hereafter. ‘Someone’, he says, ‘has me fast within his ample palm.’ Who? The answer is not slow in coming. His angel tells him: ‘My Father gave in charge to me this child of earth, e’en from its birth to serve and save, alleluia, and saved is he. This child of clay to me was given to rear and train by sorrow and pain in the narrow way, alleluia, from earth to heaven.’

Recipe for Prayer

‘My dear …

I expect the interior peace you would like to have is not attainable under the circumstances. But there is another peace, which consists in simply willing what God wills, even though it seems to be just the unpleasant distraction and exteriorising which one supposes to be bad for one. The only thing is to accept all the circumstances of one’s life, and all the effect they seem to produce upon one, and use them as means of annihilating one’s own will, cheerfully and willingly. There is no other recipe for prayer, I think. Ever yours affect.,

fr John Chapman OSB.’

A letter dated 30 June 1914 from Abbot Chapman’s Spiritual Letters.

Finding Your Feet

In a virtuoso paean to scansion, ‘fear for the layman, opportunity for the academic to display his obfuscating expertise, alas’, Craig Raine reflects on the importance of developing an ability to listen with intelligence. The rhythm of poetry (and prose) supposes acoustic exercise. ‘Metrical variation occurs when the assimilation of the part to the whole sounds forced and unnatural. The ear decides. But you have to have one.’ Not everyone does. By way of example Raine performs a deft analysis of Auden’s poem Night Mail. Re-reading these familiar lines made me want to watch again the 1936 film with the same title, which Auden coproduced. It left me thoughtful, and touched. The film presents the image of a nation with self-confidence, of high ideals of collaboration, of a people eager to stay in touch with itself. Qualities hard to come by in today’s Europe, which nonetheless yearns for them. Auden’s poem features in the final three and a half minutes of the film.

Fischer

Alfred Brendel has spoken of everything he owes the great Edwin Fischer, once remarking that he had never heard anyone make the piano sing like Fischer. One can hear what he means in this recording of Beethoven’s fourth concerto. The first movement cadenza is moving. Is it Fischer’s own? The greatest marvel, though, is the beginning of the second movement, which, as Ingmar Bergman observed in a famous radio speech, is a reluctant dialogue between the orchestra and the piano. ‘Beethoven lets the orchestra be in a bad mood – just listen and hear how angry it is! Then the piano comes in and says: “I will comfort you”‘, only to be told, ‘No one can comfort me!’ The piano, however, doesn’t give up: ‘What tenderness!’ ‘Eventually the orchestra starts listening, and the movement ends in peaceful understanding.’ Fischer draws us into this parable of gracious perseverance.

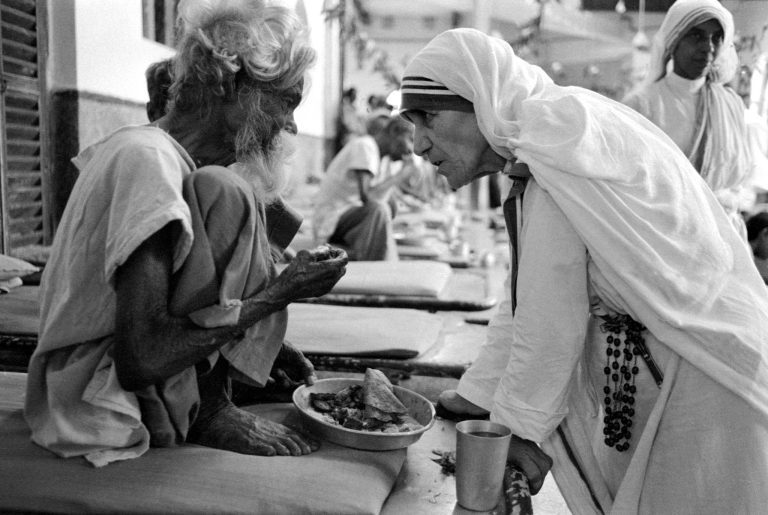

Don’t Procrastinate

From today’s Mass reading (Proverbs 3.27-34):

‘My son, do not refuse a kindness to anyone who begs it, it is in your power to perform it. Do not say to your neighbour, “Go away! Come another time! I will give it to you tomorrow”, if you can do it now.’

It can seem, perhaps, a simple counsel, but in fact, if taken seriously, the path indicated here is of high charity and self-transcendence. I have seen with my own eyes that it can be a path to holiness.

Presence

This bust of Marcus Aurelius, produced in the late second century, was acquired by Norway’s National Gallery in 1966. Standing in front of it this morning I was entranced. To call it lifelike is a banal understatement. There is life in it, somehow, and a quality of presence that carries through the centuries. What vitality there can be in marble; and how inadequate the verbiage we leave behind, now, as our putative legacy to posterity is to a single such portrait. The emperor is still young; an adolescent beard is struggling to form. What is striking is his gaze – probing, intelligent, lucid, and not at peace. We are confronted with the face of one alert to the earnestness of existence. It makes me think of a phrase from the Meditations: ‘Do not act as if you had ten thousand years to throw away. Death stands at your elbow. Be good for something while you live and it is in your power’ (IV.17).

Election & Call

Pope Francis has often referred movingly to the reading from St Bede that the Church gives us today, on the feast of St Matthew, especially to the phrase ‘miserando atque eligendo’, his episcopal motto. It is characteristic of Bede, that most humane of writers, to highlight the mercy at work in Christ’s election of his apostle – for a call is always gratuitous, independent of any merit real or imagined. It is equally characteristic that he, a monk through and through, should stress the utter self-surrender that must mark our response to such mercy, for to follow Jesus, he says, means ‘imitating the pattern of his life, not just walking after him’. Jesus subverted Matthew’s familiar world, not obliterating it, but showing its insufficiency to fulfil the supernatural desire that lay dormant in him. In this respect the drama of the apostle’s call remains paradigmatic for us all. It challenges us to consider afresh our own call and our loyalty to it now.

In His Totality

In a retreat talk given to the clergy of Tromsø this week, Sr Pauline Bürling OP reminded us of the example of Father Alfred Delp, executed by Hitler’s regime in 1945 at the age of 37 for his staunch, active resistance to Nazism. She cited the notorious public prosecutor Roland Freisler, who remarked to Delp’s friend Count von Moltke: ‘Christians and we national socialists have this in common: we make a claim to man in his totality.’

There is a categorical distinction, though. The claim of Christianity liberates, broadening human personhood immeasurably, enabling communion; whereas secular totalitarianisms restrict life, suffocating it in fearful isolation. It is good to be recalled to the stakes involved, to be reminded of courageous exemplars.

To Be Free

In a note posted yesterday, reflecting on a recent encounter with President Zelenskyi, Timothy Snyder develops what he calls ‘the Zelenskyi paradox’. It is his shorthand for the insight that ‘a free person can sometimes only do one thing. If we think of freedom as just our momentary impulses, then we can always try to run. But if we think of freedom as the state in which we can make our own moral choices and thereby create our own character, we might reach a point where, given who we have chosen to become, we have only one real choice. That was how Zelenskyi described his decision to stay in Kyiv: as not really a decision, but as the only thing he could have done and still remained true to himself. It was not only about defending freedom, although of course it was, but about remaining a free person.’ In fact this insight corresponds perfectly to Augustine’s, to which I regularly refer, that to be truly free is to have no choice to make, being fully configured to the good, true, and beautiful.

Evangelisation

From a press statement of the Nordic Bishops’ Conference: “Bishop Erik Varden OCSO (50), Bishop Prelate of Trondheim and Apostolic Administrator of Tromsø, was elected new president of the Nordic Bishops’ Conference. Bishop Raimo Goyarrola (55), bishop of Helsinki, was elected vice-president. Bishop David Tencer (61), bishop of Reykjavik, was re-elected as the third member of the Permanent Council. […] In a first statement Bishop Varden said: ‘The conference’s task is essential in order to nurture our endeavour of evangelisation through deep conversations and trustful friendship. The Catholic presence in our countries is growing. We want to accompany this growth intelligently and to support all good initiatives.’ He further stated: ‘Our post-secular society is opening itself anew to metaphysical questions and spiritual values. Many people are searching. Christ is and remains the light of the world, the goal of human existence! It is our responsibility to represent him credibly and faithfully’.”

Contemplation

The word ‘contemplation’ is currently on many lips. It is a good thing. Many aspire to attain deep prayer. They long to ‘see God’, which is an eminently Scriptural aspiration. How often, though, the spiritual quest is treated, even in manuals of prayer, as if it were distinct from the general demands of Christian discipleship. We need the realism of St Bernard in the text which the Church this morning lets us read at Vigils: ‘The first stage of contemplation is to consider constantly what God wants, what is pleasing to him, and what is acceptable in his eyes. We all offend in many things; our strength cannot match the rightness of God’s will and cannot be joined to it or made to fit with it. So let us humble ourselves under the powerful hand of the most high God and make an effort to show ourselves unworthy before his merciful gaze, saying Heal me, Lord, and I shall be healed; save me and I shall be saved […]. Once the eye of the soul has been purified by such considerations, we no longer abide within our spirit in a sense of sorrow, but abide rather in the Spirit of God with great delight. No longer do we consider what is the will of God for us, but rather what it is in itself. For our life is in his will. Thus we are convinced that what is according to his will is in every way better for us, and more fitting. And so, if we are concerned to preserve the life of our soul, we must be equally concerned to deviate as little as possible from his will.’ From Sermo V de diversis, 4-5.

Wakolda

Lucía Puenzo’s Wakolda appeared to mixed reviews ten years ago. The Holocaust film, like the Holocaust book, is apt to meet a tired groan – ‘Not another!’ – yet there is something new here, at once timely and timeless. Not only is Alex Brendemühl’s portrayal of Mengele elegantly credible; it manages to make this singularly perverse personage somehow typical, so recognisable. ‘I measure and weigh what interests me’, he says; then, ‘I have a taste for beauty’. The underlying aestheticism, the pretension to perfect the race in view of putative ennoblement, necessitating by way of collateral damage obliteration of specimens subpar, brings this historical fiction close. Wakolda portrays human presumption gone off the rails, unsubmitted to any accountability; and that is increasingly the new normal. Any historical analogy is specious. When it comes to an exceptional tragedy like the Shoah utmost caution is called for. Yet the shivers sent down one’s spine by Puenzo are not just retrospective. They regard the reality of what we have become; of that to which we have largely surrendered.

Sealed Revelations

As so often, I find a life-giving, challenging perspective on life in Paulina Mariadotter. On 10 October 1963 she noted in her prayerbook:

‘All Gods’ revelations are sealed until our obedience breaks the seal – in the very moment in which you obey, light erupts. Obey God wherever he does show you his will, and at once the next question awaiting you will become apparent.’

It is Newman’s ‘one step enough for me’ in experiential clarity. And the key to a life concretely based on faith.

Jargoning Jackdaws

These days I daily read a page or two of Between Two Eternities: A Helen Waddell Anthology or of Mediaeval Latin Lyrics, astonished at the intelligence and musicality of Waddell’s renderings, which sweep away the distance merely apparently created by the passing of centuries. Richard Ellis Roberts, translator of Peer Gynt, wrote of Waddell’s poetic versions: ‘Not a translation fails to be an original poem; and not a translation fails to give with an entrancing fidelity, the meaning and the spirit of the original.’ One can hardly imagine higher praise. And it is warranted. Consider this tenth-century poem passed on to us in MSS of Canterbury and Verona, a mariology in miniature, consummately constructed:

Norwegian Schizophrenia

This year Norway has celebrated its millennium of Christian legislation, apparently with unanimous enthusiasm. We have celebrated the fact that Norway in 1024 went from being a society ruled by might to becoming one founded on right; the recognition of women, children, and thralls as legal subjects; the establishment of ‘values’ making up what our Constitution calls our Christian inheritance. What are we to say when the government, this same year, pushes through a new abortion law that consistently avoids the reference to the unborn as ‘children’, forfeits the hitherto decisive category of ‘capacity for life’ in discernment, thereby affirming that it is legal now, on the the state’s own terms, for one human being autonomously to take another human being’s life? This coincidence indicates a kind of schizophrenia it is considered bad form to name; but it must be done. During a hearing this spring, Norway’s Council of Catholic Bishops asked for the proposed law to be rejected. We put the question: ‘Is it to Norway’s benefit to develop legislation sentimentalising the very notion of personhood, ascribing personhood to a wanted individual but withholding recognition of personhood from one that is unwanted, and on this basis expediting that individual either towards survival or to death?’ We answered: ‘We hold that it is not to Norway’s benefit to develop such legislation.’ This we still hold. We regret the implementation of this development, and the silence surrounding it.

Thorir Hund

With interest I have read Heidi Frich Andersen’s novel But Outside are the Dogs about Thorir Hund, one of the men who killed St Olav at Stiklestad on 29 July 1030. The historical novel is a demanding genre. One risks anachronism at several levels, and simplistic perspectives on the past. Frich Andersen navigates steadily and well. She bases herself securely on saga literature. When she uses her imagination it is, as it were, within these parameters. She conveys the complexity of human lives and choices a thousand years ago. In her account the story of Thorir’s conversion and pilgrimage to Jerusalem seems not inevitable, but humanly possibly, indeed credible. In addition she lets us sense how the canonisation of Olav may have impacted on contemporaries’ sensibility. The Latin that is regularly cited has been rather hashed, alas. I asked myself whether this was by way of literary strategy. The story is presented as Thorir’s own written account. He is unlikely to have had much by way of Latin culture. Still, had he consistently mixed up spelling and declensions, he is unlikely to have written such elegant riksmål. Still, this is a marginal blemish. The book is highly readable. It makes one think. And that it is good.

Martyrdom

‘We know Herod to have been a weak ruler, conceited and unprincipled. How gladly he listened to John! How cavalierly he ignored what he heard!

Over and beyond such spinelessness, today’s account presents him in a light that is positively lurid. Reclining at an executive luncheon, he is so enthralled by the suggestive charms of his stepdaughter that he promises to give her anything —well, almost anything—to show his appreciation. The gruesome request that followed shook him, yet Herod was bound by his word, his vain and presumptuous word. John was executed forthwith, with the guests still at table.

A lecherous king, a jealous queen, a fickle child: should these bring the Old Testament to a close?’

From a homily for the feast of the Beheading of John the Baptist.

Like a Bad Habit

In a cogent essay Timothy Snyder engages with the distorted reading of history that underpins Russia’s ongoing war of aggression against Ukraine. The framework he uses, reminding us to check projections and downright inventions against facts, can be applied to other situations, too. ‘When confronted with magical thinking by dictators, historians feel out of place, like a bridge player invited to judge prestidigitation, say, or a surgeon hired to care for wax figures. Putin is in love with a legend. Historically speaking, this is very familiar: new regimes, such as Putin’s, seek compensation in myths of ancient origin. Putin’s idea of Russia, his justification for the killing of hundreds of thousands of people, his rationalization of his attempt to destroy Ukraine as a people — it all rests on a very familiar sort of tall tale: we were here first. These stories are generally complete falsehoods, from the “we” through the “were” and the “here” and the “first.” And so it is for Putin. But the stories get repeated so often that they take on a kind of leaden plausibility, like a bad habit.’ After unpicking these stories, Snyder concludes: ‘Were Putin to follow his own logic, he would not be invading Ukraine, but handing over European Russia to Finland or Sweden.’

Venice at Dawn

Lawrence Durrell in Bitter Lemons: ‘These thoughts belong to Venice at dawn, seen from the deck of the ship which is to carry me down through the islands to Cyprus; a Venice wobbling in a thousand fresh-water reflections, cool as a jelly. It was as if some great master, stricken with dementia, had burst his whole colour-box against the sky to deafen the inner eye of the world. Cloud and water mixed into each other, dripping with colours, merging, overlapping, liquefying, with steeples and balconies and roofs floating in space, like the fragments of some stained-glass window seen through a dozen veils of rice-paper. Fragments of history touched with the colours of wine, tar, ochre, blood, fire-opal and ripening grain. The whole at the same time being rinsed softly at the edges into a dawn sky as softly and circumspectly blue as a pigeon’s egg.’

Chat GPT just couldn’t do that.

Love as We Know it

In a letter to her sister Meg, Helen Waddell, ever an uncompromising seeker after truth, after the real, wrote:

‘What if it were really true that the power at the back of this cruel universe were love as we know it? It’s no wonder Dante said when he had that vision of ‘love that moves the sun and stars’ that it was tanto ottraggio, a kind of outrage of his being. For to come within the least whisper of it is to leave one gasping … it is so terrible that one almost looks about for familiar little shelters of noise and buses to shut out the stars.’

There is authority in this affirmation, a reminder that much pedestrian, pious prattle about ‘the love of God’ presenting it as an existential tea-cosy issues from lack of experience of what the reality designates in fact. Hebrews 10.31.