The Crow

A fresh encounter with a movement from Schubert’s Winterreise becomes for Daniel Capó an occasion to reflect on the underlying malaise of our time. He writes, ‘The question of art is, above all, one that probes each of us and opens the future to new paths. Schubert’s romanticism, with its burden of anguish, translates into our era with all the hallmarks of the twentieth century: mass destruction, totalitarianism, the indiscriminate use of propaganda, rock music… No society can emerge unscathed from these experiences, nor can any recreation we attempt of past or present. Like the wanderer who sings in Winterreise, we journey in search of an authentic home. Civilization thus springs from a simple gesture repeated through time: welcoming hands and recognizing eyes that preserve us from dissolution.’ You can read his essay in its entirety here.

Angelus

Early this morning, standing at the bus stop in the rain, I suddenly heard the Angelus from St Olav’s cathedral pour out over the cityscape in sonorous benediction. Little gives me as much comfort as the sound of the Angelus bell. It is a marker of civilisation, a proclamation at once discreet and majestic of life’s purpose and sense, direction and finality, spreading its beneficial reach to those, too, who have not the slightest idea of what it stands for. I think of a few lines by Jehan Le Povremoyne set to music by Vierne: ‘The Angelus sounds across my city still asleep; the Angelus of bells in honour of Mary. See how the night flees. How joyfully the Archangel’s greeting resounds upon my city still asleep. As the doe’s fawn behind the hill, the sun will leap forth.’

Inner Structure

I recently came across an excerpt from a conference Cardinal Stanislas Dziwisz gave at the University of Lublin in 2001. Dziwisz, who had been John Paul II’s private secretary, recalled the aftermath of the assassination attempt in St Peter’s Square on 13 May 1981. Rushed to the Gemelli Hospital John Paul II was instantly submitted to surgery while the world held its breath and the whole Church prayed. When after some days the pope regained consciousness, opened his eyes, and prepared to speak, everyone was expectant. What profound mystical utterance would he make, after standing on the threshold between life and death? Dziwisz says that his first words were: ‘Have we said Compline?’ I find this a touching testimony. It shows the extent to which the inner life of this great Christian, artist, intellectual and statesman, was structured by the prayer of the Church; and is an incentive to remain radically faithful to it, certain that it will provide the nourishment needed for whatever task providence assigns us.

Queen of the Night

I gather there’s a plan to reboot Amadeus on Sky. Good luck to them. I’ve never understood why people bother to tamper with artistic creations that, within their idiom, achieve something close to perfection – like ridiculously remaking Brideshead. The producer’s promise of ‘a corrupting symphony of jealousy, ambition and genius’ is quite enough to make me resolve not to see the film. Mozart will forever remain a mystery unfathomable. The truest thing that can be said about him is what Piotr Anderszewski says in Monsaingeon’s portrait: ‘I have never been able to reconcile myself to the premature death of Mozart.’ Yet there’s something about the Miloš/Shaffer Amadeus that comes across as definitive. I love this scene in which a telling-off from a fierce mother-in-law makes Mozart touch the essence of one of opera’s most original characters. He must have operated a bit like that. If we were to discover just a fragment of his secret of sensation, how interesting, how rich life would be.

Blindness & Sight

The trajectory traced by St Teresa of Ávila reaches from the outset right to the loftiest end of spiritual life. She counsels souls who wobble ‘like hens, with feet tied together’ but also those who soar like eagles. Nor does she forget the perplexing darkness of the long intermediate stage when the soul, like a timid dove, is dazzled by rare glimpses of God’s Sun while, ‘when looking at itself, its eyes are blinded by clay. The little dove is blind’. Everything she writes, she tells us, is born of experience. For long years she herself ‘had neither any joy in God nor pleasure in the world’. She lived in an in-between state, a no-woman’s land. What changed it? No summary can do justice to her subtle account of the transformative miracle wrought in her by God. We can, though, get some sense of its impact. Teresa testifies how, at a decisive juncture, ‘todos los que me conocían veían claro estar otra mi alma’: her soul had become other; it was no longer what it used to be.

Vince malum in bono

Ordene var mottoet til Biskop Jurgis Matulaitis, en av det tyvende århundres store bekjennere. Han var en lærd mann, en bønnens mann som elsket Kirken og utgjøt seg for henne. Han elsket også sitt Litauen, som han bidro til å bygge opp ved å nære, etter århundrers russisk dominans, landets særegne arv og på samme tid dets kulturelle og etniske mangfold. Biskop Matulaitis var en klok veileder, som uredd kalte en spade en spade. Her er et utdrag fra et brev han skrev i 1913 til en ung mann som ville bli prest: ‘Jeg har inntrykk at dine tvil har sitt opphav her: Du lar deg dominere helt av eget ego. Ditt liv beveger seg rundt din egen person som på en akse. Gjerne ville du sette deg selv og ditt levnet i banken, slik at egoet kunne tjene mest mulig renter. Du ønsker å beskytte og forsikre deg selv slik at ditt ego ikke går under eller utsettes for ulykke. Men selv de forsiktigste folk opplever iblant at de ikke er i stand til å holde på egen kapital.’ Biskop Matulaitis ble saligkåret av Pave Johannes Paul II i 1987. Du finner en masse ressurser på engelsk, deriblant hans åndelige dagbok, på denne siden.

The Woods

Writes Helen Waddell about Boethius:

‘It was fortunate for the sanity of the Middle Ages that the man who taught them so much of their philosophy was of a temperament so humane and so serene; that the ‘mightiest observer of mighty things’, who defined eternity with an exulting plenitude that no man has approached before or since, had gone to gather violets in a spring wood, and watched with a sore heart a bird in a cage that caught a glimpse of waving trees, and now grieved its heart out, scattering its seed with small impotent claws’:

Interesting After All

Any writer hopes to interest his readers, not necessarily to convince them, but to make them reflect, and to count the time well spent. So I was happy to discover Harry Readhead’s recent review of Chastity. He writes: ‘Chastity is a curious little book. It is immensely readable, yet deals with something I never thought I would find remotely interesting. It reconsiders and reframes a virtue that has long been understood simplistically and scornfully. By the time the curtain, as it were, comes down, we have the impression that chastity, in its broadest definition, communicates something noble, something admirable, something freeing and — ironically — something desirable. We are, in other words, persuaded by the author’s argument, which is subtle but insistent, clothed in the language of reflection and meditation: for it is an argument for a life lived on our own terms, liberated by the racket and noise of ego.’

Guardian Angels

The beginning of Newman’s poem The Dream of Gerontius speaks of a marvellous encounter. Just as Gerontius leaves this world, he realises he is not alone. A mysterious, discreet companion accompanies him into the hereafter. ‘Someone’, he says, ‘has me fast within his ample palm.’ Who? The answer is not slow in coming. His angel tells him: ‘My Father gave in charge to me this child of earth, e’en from its birth to serve and save, alleluia, and saved is he. This child of clay to me was given to rear and train by sorrow and pain in the narrow way, alleluia, from earth to heaven.’

Oppskrift for bønn

‘Min käre Swinstead! Jag skulle tro att ni under omständigheterna inte kan uppnå den inre frid ni skulle vilja ha. Men det finns ett annat slags inre frid som innebär att vi helt enkelt vill det som Gud vill, även om det tycks vara just den otrevliga förströddhet och den utåtvändhet som vi förmodar är skadliga för oss. Det enda som krävs är att vi accepterar alla våra livsomständigheter och den verkan som dessa utövar på oss, och att vi glatt och villigt använder dem som ett medel att tillintetgöra vår egen vilja. Det finns inget annat bönerecept tror jag. Er alltid tillgivne F John Chapman OSB.’

Et brev datert 30 juni 1914 fra Abbed Chapmans åndelige brev, en uforlignelig bok om bønn, vakkert og trofast oversatt til svensk av en nonne i Hillerød under tittelen Allt är bra när allt känns fel.

Om verseføtter

In a virtuoso paean to scansion, ‘fear for the layman, opportunity for the academic to display his obfuscating expertise, alas’, Craig Raine reflects on the importance of developing an ability to listen with intelligence. The rhythm of poetry (and prose) supposes acoustic exercise. ‘Metrical variation occurs when the assimilation of the part to the whole sounds forced and unnatural. The ear decides. But you have to have one.’ Not everyone does. By way of example Raine performs a deft analysis of Auden’s poem Night Mail. Re-reading these familiar lines made me want to watch again the 1936 film with the same title, which Auden coproduced. It left me thoughtful, and touched. The film presents the image of a nation with self-confidence, of high ideals of collaboration, of a people eager to stay in touch with itself. Qualities hard to come by in today’s Europe, which nonetheless yearns for them. Auden’s poem features in the final three and a half minutes of the film.

Fischer

Alfred Brendel har ofte snakket om alt han skylder den store Edwin Fischer. Han bemerket en gang at han visst aldri hadde hørt noen få pianoet til å synge lik Fischer. Man skjønner hva han mener ved å lytte til denne innspillingen av Beethovens fjerde klaverkonsert. Kadensen i første sats er storartet. Er den Fischers egen? Men det store vidunder er annensatsen som, slik Ingmar Bergman bemerket i et berømt kåseri, er en skeptisk dialog mellom orkester og piano. ‘Beethoven lar orkesteret være i dårlig humør, bare hør hvor sint det er!’ Så kommer pianoet inn og sier, «Jeg skal trøste deg, jeg»‘, bare for å få til svar: ‘Ingen kan trøste meg!’ Pianoet gir dog ikke opp: ‘For en ømhet!’ ‘Til slutt begynner orkesteret å lytte, og satsen slutter i fredelig overenskomst.’ Fischer trekker oss inn i den lignelsen om grasiøs utholdenhet.

Utsett ikke

Fra dagens messelesning (Ordspråkene 3.27-34):

‘Min sønn, gjør godt mot dem som trenger det, nekt ikke å hjelpe om det står i din makt! Si ikke til din neste: «Gå din vei, og kom igjen i morgen, så skal du få!» – så sant du har noe å gi ham nå.’

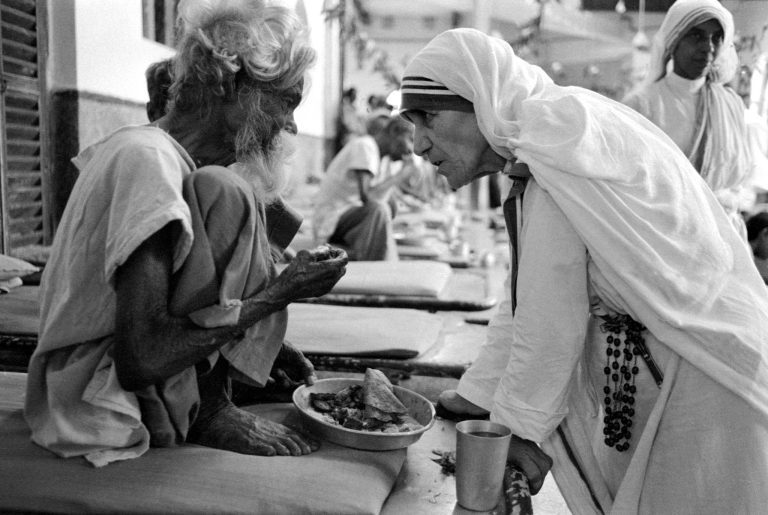

Dette kan synes lettvint, kanskje; men i virkeligheten står holdningen, hvis vi tar den på alvor, for en høy grad av nestekjærlighet og selvovervinnelse. Jeg har med egne øyne sett at den kan føre et menneske til hellighet.

Nærvær

Denne bysten av Marcus Aurelius, laget mot slutten av det annet århundre, ble anskaffet av Nasjonalgalleriet i 1966. Jeg stod foran den som fjetret i formiddag. Å kalle den livaktig er utilstrekkelig; det er liv i den på forunderlig vis, et slags nærvær forblitt gjennom århundrene. Det er forunderlig at marmor formidler slik vitalitet. Og det slår meg: Alt det pjatt vi etterlater oss, nå, som vår ‘arv’ til ettertiden (kilometervis med smilefjes og utropstegn) veier mindre enn en eneste forstenet hårlokk på et slikt portrett. Keiseren er ung ennå: fjortisbarten strir med å etablere seg. Det mest slående er imidlertid blikket – utforskende, intelligent, klarsynt, og fredløst. Vi ser ansiktet til én som er seg tilværelsens alvor bevisst. Det får meg til å tenke på et avsnitt i Meditasjonene: ‘Lev ikke som om du hadde ti tusen år å kaste bort. Døden står ved din albue. Gjør da nytte for deg mens du lever, mens du kan’ (IV.17).

Utvalgt & benådet

Pope Francis has often referred movingly to the reading from St Bede that the Church gives us today, on the feast of St Matthew, especially to the phrase ‘miserando atque eligendo’, his episcopal motto. It is characteristic of Bede, that most humane of writers, to highlight the mercy at work in Christ’s election of his apostle – for a call is always gratuitous, independent of any merit real or imagined. It is equally characteristic that he, a monk through and through, should stress the utter self-surrender that must mark our response to such mercy, for to follow Jesus, he says, means ‘imitating the pattern of his life, not just walking after him’. Jesus subverted Matthew’s familiar world, not obliterating it, but showing its insufficiency to fulfil the supernatural desire that lay dormant in him. In this respect the drama of the apostle’s call remains paradigmatic for us all. It challenges us to consider afresh our own call and our loyalty to it now.

I helhet

I et retrettforedrag til prestene i Tromsø denne uken, snakket Sr Pauline Bürling om jesuitten Alfred Delp, henrettet av Hitlers regime i 1945, bare 37 år gammelt, for sin aktive motstand mot nazismen. Hun siterte den beryktede anklageren Roland Freisler som sa til Delps gode venn Grev von Moltke: ‘Kristne og vi nasjonalsosialister har dette til felles: Vi fordrer det hele menneske.’

Men der finnes en kategorisk forskjell. Den kristne fordring frigjør, lar menneskelig personlighet utfolde seg grenseløst og åpner for fellesskap; sekulær totalitarisme derimot begrenser livet, og kveler individet i fryktelig isolasjon.

Det er nyttig å minnes om dramaets innebyrd – og om forbilder vi kan se til.

Å være fri

In a note posted yesterday, reflecting on a recent encounter with President Zelenskyi, Timothy Snyder develops what he calls ‘the Zelenskyi paradox’. It is his shorthand for the insight that ‘a free person can sometimes only do one thing. If we think of freedom as just our momentary impulses, then we can always try to run. But if we think of freedom as the state in which we can make our own moral choices and thereby create our own character, we might reach a point where, given who we have chosen to become, we have only one real choice. That was how Zelenskyi described his decision to stay in Kyiv: as not really a decision, but as the only thing he could have done and still remained true to himself. It was not only about defending freedom, although of course it was, but about remaining a free person.’ In fact this insight corresponds perfectly to Augustine’s, to which I regularly refer, that to be truly free is to have no choice to make, being fully configured to the good, true, and beautiful.

Evangelisering

Fra en presseuttalelse fra Den nordiske bispekonferanse: «Biskop Erik Varden OCSO (50), Biskop av Trondheim og Apostolisk Administrator av Tromsø, ble valgt som ny formann for Den nordiske bispekonferanse. Biskop Raimo Goyarrola (55), biskop av Helsinki, ble valgt til viseformann. Biskop David Tencer (61), biskop av Reykjavik, ble gjenvalgt som tredje medlem av konferansens permanente råd. […] I et første utsagn sa Biskop Varden: ‘Konferansen har en vesentlig oppgave når det gjelder å nære vår evangeliserende innsats gjennom dype samtaler og tillitsfullt vennskap. Det katolske nærvær i våre land vokser. Vi ønsker å ledsage veksten på intelligent vis; vi ønske å støtte alle gode tiltak.’ Han sa videre: ‘Vårt post-sekulære samfunn åpner seg på nytt for metafysiske spørsmål og åndelige verdier. Mange mennesker er søkende. Kristus er og forblir verdens lys, målet for menneskets eksistens! Det er vårt ansvar å representere ham trofast og troverdig.’

Kontemplasjon

The word ‘contemplation’ is currently on many lips. It is a good thing. Many aspire to attain deep prayer. They long to ‘see God’, which is an eminently Scriptural aspiration. How often, though, the spiritual quest is treated, even in manuals of prayer, as if it were distinct from the general demands of Christian discipleship. We need the realism of St Bernard in the text which the Church this morning lets us read at Vigils: ‘The first stage of contemplation is to consider constantly what God wants, what is pleasing to him, and what is acceptable in his eyes. We all offend in many things; our strength cannot match the rightness of God’s will and cannot be joined to it or made to fit with it. So let us humble ourselves under the powerful hand of the most high God and make an effort to show ourselves unworthy before his merciful gaze, saying Heal me, Lord, and I shall be healed; save me and I shall be saved […]. Once the eye of the soul has been purified by such considerations, we no longer abide within our spirit in a sense of sorrow, but abide rather in the Spirit of God with great delight. No longer do we consider what is the will of God for us, but rather what it is in itself. For our life is in his will. Thus we are convinced that what is according to his will is in every way better for us, and more fitting. And so, if we are concerned to preserve the life of our soul, we must be equally concerned to deviate as little as possible from his will.’ From Sermo V de diversis, 4-5.

Wakolda

Lucía Puenzos film Wakolda ble litt ujevnt anmeldt da den utkom for ti år siden. Det har vært en industriell produksjon av Holocaust-filmer og -bøker, så folk er skeptiske. Men der er noe her som er nytt, på samme tid tidløst og samtidsrelevant. Alex Brendemühls fremstilling av Mengele er troverdig. Ja, den får denne sjeldent perverse person til å fremstå forunderlig typisk, og derved gjenkjennelig. ‘Jeg måler og veier det som interesserer meg’, sier han; deretter, ‘Jeg er følsom for det vakre.’ Den underliggende estetismen, formålet om å fullkommengjøre rasen utifra et innbilt foredlende ideal som medfører, i form av nødvendig konsekvens, utslettelsen av undermåls eksemplarer, gjør at en historisk fiksjon kommer oss nær. Wakolda viser oss stormannsgalskap gått av skaftet, ikke lenger svarende til noen instans; og det er nå engang en slags ny norm. Enhver historisk analogi er tvilsom. Når det gjelder en unik tragedie som Shoah skal man utøve den aller største forsiktighet. Allikevel: Når vi grøsser oss gjennnm Puenzos film, er det ikke utelukkende på grunn av tilbakeskuende erindring. Utilpassheten gjelder noe vi faktisk er blitt, noe vi har overgitt oss selv til.

Forseglet Åpenbaring

Som så ofte, finner jeg et livgivende, utfordrende perspektiv på livet hos Paulina Mariadotter. Den 10. oktober 1963 noterte hun i sin andaktsbok:

‘Alla Guds uppenbarelser är förseglade tills vår lydnad bryter inseglet – i samma stund du lyder bryter ljuset fram. Lyd Gud på varje punkt där han visar dig sin vilja, och genast ligger nästa spörsmål klart för dig.’

Det er Newmans ‘eitt steg er nok åt meg’ i erfaringsbasert klarhet. Og nøkkelen til konkret trosbasert levnet.

Teologi fra naturen

Nå om dagen leser jeg daglig en side eller to fra Between Two Eternities: A Helen Waddell Anthology eller fra Waddells Mediaeval Latin Lyrics, forundret over innsikten og musikaliteten i hennes oversettelser. De baner vei gjennom tid og får tusen år-gamle tekster til å klinge spontant. Richard Ellis Roberts, som selv oversatte Peer Gynt, skrev om Waddells oversettergjerning: ‘Ikke én oversettelse er mindre enn et eget, opprinnelig dikt; på samme tid kommer ikke én oversettelse til korte når det gjelder forbløffende nøyaktighet, ved å gjengi grunntekstens mening og ånd.’ Et lødigere kompliment kan man knapt tenke seg. Og det er fortjent. Ta for eksempel dette diktet fra 900-tallet, som vi har fra manuskripter i Canterbury og Verona. Det utgjør en mariologi i miniatyr, mesterlig oppbygd:

Norsk schizofreni

Norge har i år feiret tusenårsjubileum for kristenretten, øyensynlig med allmen begeistring. Fromt er det blitt sunget over det ganske land om Guds fire døtre. Vi har ropt hurra for at Norge i 1024 gikk fra å være maktsamfunn til å bli rettssamfunn; for anerkjennelsen av kvinner, barn og treller som rettssubjekter; for funnet av “verdier” som utgjør det Grunnloven kaller vår kristne arv. At regjeringen nettopp i år presser gjennom en ny abortlov som konsekvent unnlater å omtale fostre som ‘barn’, som kaster levedyktighetsprinsippet på båten og derved befester at det er lovlig, på statens premisser her til lands, for ett menneske å ta et annet menneskes liv, vitner om en kollektiv schizofreni det er ille ansett å omtale. Men det må til. Norsk katolsk bisperåd analyserte lovforslaget i vår og bad om at det skulle forkastes. Vi spurte: ‘Er Norge tjent med en utvikling av lovverk som åpner for sentimentalisering av selve personbegrepet, som tilskriver et ønsket individ personlighet, mens et uønsket individ fraskrives personlighet, og som på dette grunnlag ekspederer individet enten mot liv eller død?’ Og svarte så, ‘Vi mener at Norge ikke er tjent med slik utvikling.’ Det mener vi fortsatt. Vi beklager dypt at utviklingen tross alt finner sted, tilsynelatende uten at så mange bryr seg. Lytt til min samtale med Sr Anne Bente Hadland om emnet her.

Tore Hund

Med interesse har jeg lest Heidi Frich Andersens Men utenfor er hundene om en av hellig Olavs banemenn. Den historiske roman utgjør en vrien genre. Man risikerer anakronismer på flere plan, og forenklende fortidsperspektiver. Frich Andersen navigerer imidlertid stødig og godt. Hun baserer seg trygt på sagalitteraturen. Når hun bruker fantasien er det, så å si, innenfor sagaens rammer. Hun formidler kompleksiteten i menneskers liv, i valgene de møtte, for tusen år siden. I hennes gjenfortelling synes beretningen om Tore Hunds omvendelse og pilegrimsferd til Jorsal på intet vis uunngåelig, men menneskelig mulig, ja, ikke usannsynlig. Hun skriver godt, stilrent. Latinen som stadig forekommer er dessverre ganske maltraktert. Jeg vet ikke om det er tenkt som litterært virkemiddel? Historien gir seg ut for å være Tores opptegnelse. Noen stor latinsk kultur hadde han neppe. Men hadde han så gjennomført gått på tverke med deklinasjoner og rettskriving, ville han neppe ha ført et så tydelig riksmål. Nå, dette er en marginal skavank. Boken er leseverdig. Den maner til ettertanke. Og det trengs.

Martyrium

‘Vi vet at Herodes var en svak hersker, jålete og prinsippløs. Så gjerne han lyttet til Johannes! Så lett han ignorerte det han hørte!

Utover Herodes’ moralske slapphet, får vi i dag et bilde av ham som er bentfrem sjaskete. I det han lener seg tilbake ved bordet ved en dyr middag, forhekses han i den grad av sin stedatter at han lover å gi henne alt — vel, nesten alt — som tegn på sin verdsettelse. Den fryktelige forespørsel som følger sjokkerer ham, men Herodes er bundet av sitt ord, sitt forfengelige og overmodige ord. Johannes ble henrettet med det samme, mens gjestene ennå satt til bords.

En kåt konge, en misunnelig dronning, et selvgodt barn: Skulle disse da føre Det Gamle Testamente til ende?’