Words on the Word

Good Friday

Here you can find a recording of the Good Friday Passion from St Peter’s thirteen years ago.

The Cistercian community of Boulaur at this year’s Good Friday liturgy, during the reading of the Passion.

Isaiah 52:13-53:12: Yet ours were the sufferings he bore.

Hebrews 4:14-16, 5:7-9: We must never let go of the faith we have professed.

John 18:1-19:42: Mine is not a kingdom of this world.

Having followed Christ through his Passion, our nerves are frayed. Our heart is raw. At one level, we want to be alone, still, unthinking. At another level, we need to understand. What is the meaning of the story we have entered into? The quest for meaning is central to the Passion narrative. It reaches its crux in the exchange between Christ and Pilate.

Jesus is led to Pilate’s quarters after a night’s interrogation by clerics. The issue at stake in both settings is an issue of authority. What is the relationship between Christ and his disciples? Who do they think he is? Who does he think he is? Pilate cuts straight to the bone: ‘Are you the king of the Jews?’ Jesus defines the terms: ‘My kingdom is not of this world.’ Pilate persists: ‘So you are a king?’ Christ declares: ‘You say that I am a king. For this I was born and have come into the world, to bear witness to the truth. Everyone who is of the truth hears my voice.’

The register is moved from politics to metaphysics. Jesus does not reject the kingly title. Neither does he claim it for himself. What he does lay claim to is truth.

Truth is a big theme in the Fourth Gospel. Let’s consider three examples. Speaking with Nicodemus, Jesus says: ‘Whoever does the truth comes to the light’. Truth-seeking is not just about asking questions. The truth is something one does by leaving darkness and choosing the light. To the woman at the well, Jesus speaks of truth in connection with worship. ‘The hour will come and is now when true worshippers will worship the Father in spirit and in truth.’ Truth is a way of approaching God. Pursuit of truth is intrinsic to prayer. Then, think of Jesus’s words to the Jesus after meeting the woman caught in adultery: ‘If you continue in my word, you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.’ To know the truth is the opposite of being imprisoned. It is a state we shall attain if we continue in, and somehow inhabit, Jesus’s words. So truth is light, truth is worship, truth is freedom. By this sort of teaching the disciples are gradually prepared to grasp the words of power Christ will utter later in the Gospel, when he says: ‘I am the truth, no one comes to the Father but by me.’

Truth is not primarily notional but personal. It is life, a way to walk. It has a name and a face.

We live in times that largely reject the idea of truth. It is still OK to speak of my truth and your truth, but the notion that there might be such a thing as the truth is considered laughable, even discriminatory. Who am I to tell you what is true? The way the wind is blowing, it’s not too far fetched to imagine a day when it’s declared illegal to make objective truth claims. The dictatorship of relativism imposes itself by means of increasingly monstrous legislation. More insidiously, it extends its tentacles within, into our hearts and minds. We are conditioned to make a fetish of doubt, to wallow in a bog of indecision. This makes us at once volatile and weary, for to live is to move, and to move is to choose an orientation.

Pilate’s quip, ‘What is truth?’, might unfurl as a banner over our age. It is a rhetorical question, not a real one: it does not expect an answer. It assumes there can be no answer.

How does Truth incarnate respond? Unsettlingly. He gives no answer. In Isaiah’s terms, ‘he never opened his mouth, like a lamb led to the slaughter-house, like a sheep dumb before its shearers’. How are we to understand this? Is it not capitulation? Shouldn’t Truth have kicked and screamed, forced its way?

Purveyors of minor truths would have it so. Truth himself works otherwise. He shows that truth is not ultimately a position to be argued, but an act of committal of self to be made unconditionally. The truth, remember, sets us free. It happens time and again in history that for one man’s freedom another man must lay down his life. We honour such men as heroes. We lay wreaths on their graves.

What we witness on Good Friday is the conquest of freedom on a scale that raises time into eternity. It pierces darkness with a light that can’t go out. It defines true worship in an act of sacrificial love so vast it holds and explains the infinity of smaller sacrifices by which Truth finds access to our lives bestowing sense, peace, and beauty.

May we rise to that standard! May we never compromise with Truth, but love it, live for it — and die, if we must. The message of Good Friday is this: no brokenness is final. All fragmentation can be restored by self-giving in love. Christ has cleared the way. His cross, geometrically a sign of contradiction, a function of two lines that will never run parallel, has become a symbol of wholeness.

In this paradox Pilate’s question is answered. Crucified love is the Truth. From it flow our confidence, our hope and our joy, the joy which, in the tears of Good Friday, has its wellspring. It will irrigate our lives and make them fruitful insofar as we commit to Truth with the integrity Truth demands.

Ave Crux, spes unica. Amen.

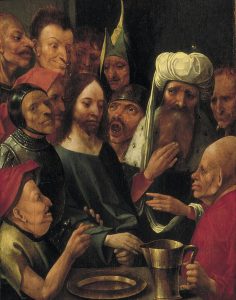

Christ before Pilate by Hieronymus Bosch, a painting now in the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. Wikimedia Commons.