Words on the Word

Wedding of Camille & Briac

The French original is available here.

2 Peter 1:16-19: We had seen his majesty for ourselves.

Matthew 17: 1-9: Rise, and have no fear.

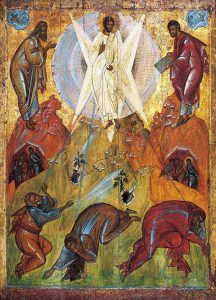

The story of the transfiguration represents a turning point in the public life of our Lord. There is a before and an after. From the outset, of course, the Lord’s uniqueness was evident in his teaching. The guards who told perplexed Pharisees, ‘Never did a man speak like this!’, spoke for countless hearers. The new words of Christ inspired some to leave everything behind to follow him. Little by little they came to suspect his divine identity. Thus Peter could cry out, at Caesarea, ‘You are the Son of the living God!’ Here we find the climax of a rational appraisal, made in the light of faith, of the person of Jesus. But it is the transfiguration, which follows immediately, which makes the essential content of Peter’s confession manifest, showing who the Son of God is.

Scripture lets us consider the transfiguration from several angles. The Gospel tells the story in sequence: the call of Peter, James, and John; the divine splendour manifest in Christ’s Body and in his clothes, for the spiritual suffuses the material; the appearance of Moses and Elijah, bringing the testimony of the Law and the Prophets; the Apostles’ terror; Jesus’s consoling voice saying, as it will say again later, after the resurrection, ‘Fear not’; finally, the descent from the mountain and the instruction, ‘Tell no one the vision, until the Son of man is raised from the dead.’

Scripture lets us consider the transfiguration from several angles. The Gospel tells the story in sequence: the call of Peter, James, and John; the divine splendour manifest in Christ’s Body and in his clothes, for the spiritual suffuses the material; the appearance of Moses and Elijah, bringing the testimony of the Law and the Prophets; the Apostles’ terror; Jesus’s consoling voice saying, as it will say again later, after the resurrection, ‘Fear not’; finally, the descent from the mountain and the instruction, ‘Tell no one the vision, until the Son of man is raised from the dead.’

For you and me, the transfiguration is above all a literary phenomenon which we approach through reading, finding here one of several stages in the unfolding of Christ’s mission, oriented towards his redemptive sacrifice.

But what about those who were present that day, on Tabor? What was the long-term impact of their confrontation with the perceptible presence of divine energy?

Our first reading speaks of just this. It conveys the ripe fruit of Peter’s reflection of what he experienced back then, while he was still young, not fully established ‘in the power of Jesus Christ’. What strikes us in his text, as in the analogous testimony of the First Letter of John, is the list of verbs that indicate concrete, even sensual experience: ‘We have seen’, ‘we have heard’, ‘we have touched’. Tabor, writes Peter, confirmed the word of the prophets. Let’s remember that the writer was a man who had struggled to believe in this word, who, on seeing his Saviour and Friend enter his passion, said, ‘I know him not.’ The passion of Christ seemed to him an eclipse which spread its darkness into his own heart. He had to wait until the third day to see the glory glimpsed on Tabor shine forth from the empty grave, so to verify that no darkness can overcome Christ’s light. Peter assures us that the Gospel has nothing to do with ‘cleverly devised myths’. It is about objective facts, constituting a rock on which man can construct the house of his existence.

Here, dear Camille and Briac, is the foundation on which you will build your married life.

After thorough discernment you have reached this day on which you will administer to one another the nuptial sacrament. The Church will confirm it with her maternal benediction. For us who walk still in the dust, the sacraments are occasions that let us glimpse the uncreated light of Tabor. For a few moments, earth becomes heavenly. The Father’s exultant voice is heard. We exclaim, ‘It is good for us to be here!’ The liturgy calls forth these flashes of supreme reality which ought to illumine the rest of our existence. Today you consecrate yourselves to one another in joy and liberty. To say to another, ‘I am yours forever!’, is magnificent, a sign of the grandeur of the human being, whose potential reaches beyond the provisional. Your mutual ‘Yes’ is simultaneously a consecration to the Lord. Yours is a sacred covenant. It will be realised by means of a horizontal axis marked, like the human condition as such, by a degree of banality, boredom, and battle; yet it will remain traversed by a vertical axis pointing towards heaven opened. The intersection of the axes is your living environment.

Marriage will be for you the state by which grace will embrace your entire being in all its dimensions. In marriage, just as in monastic life, the basic principle is the one St Benedict stresses when he enjoins: ‘Let God be glorified in all things’ (RB 56). Nothing is too small to serve this purpose: every activity, every utterance, every movement of the heart and body can become a means by which to glorify God, a liturgical worship permitting God’s glory to insinuate itself into everyday life. Even your falls will have their part to play if you, like Peter, get up at once, humbly and (this is important) without bitterness. The sacrement which illumines you this day is the pledge of ‘precious and very great promises’ whose intention is that you should ‘become partakers of the divine nature’. Stop and think of it! This proposition, likewise from the Second Epistle of Peter (1:4), sets forth a perspective so immense that we hardly dare to envisage it; yet it is the logical extension of the revelation on Mount Tabor. Divine glory is communicative and transformative. The human being is made to know the very life of God.

May your nuptial communion realise this mystery in love, faithfulness, fruitfulness, reconciliation, persevering service and hospitality to others. Then you will know the joy of God and the morning star will arise in your hearts. Amen.