Archive, Letters

A Letter to the OCSO

The General Chapter of the Order of Cistercians of the Stricter Observance is currently convened in general chapter in Assisi. The Order’s Abbot General, Dom Bernardus Peeters, invited me to address a letter to the assembly. The text can be found below. It is available also in Spanish, Italian, and French.

To the General Chapter of the OCSO,

gathered in the Domus Pacis, Assisi

1 September 2022

Dear Reverend Mothers and Reverend Fathers,

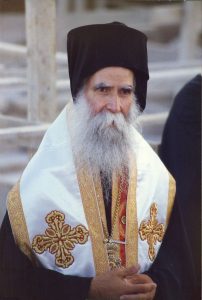

A book I have kept referring to during the past two years is Stephen Lloyd-Moffett’s life of Bishop Meletios Kalamaras, Beauty for Ashes. Meletios, born in 1933, became a monk at twenty-one. He lived a life of austerity. Appointed secretary to the Holy Synod, he moved to Athens in 1968. Young people gathered round him, longing for a renewal of the Church and radical monastic living. A community emerged. In 1979, Fr Meletios travelled with a group of twelve to Mount Athos. Their intention was to settle there, but the plan was scuppered: Meletios was appointed bishop of Preveza, near ancient Nikopolis. He assumed the charge of episcopacy while remaining fully a monk. On his arrival, the diocese was mired in scandal. Over time, transformation occurred, as the book’s title suggests. It speaks to our hearts. Who has not had the experience of seeing something dear reduced to burnt earth, then of hoping that, somehow, new beauty might arise phoenix-like out of the ashes?

How did Meletios proceed? To give an adequate answer would take too long. I shall stress only a single key insight that lies at the base of everything else. The Church, Meletios insisted, is a divine mystery and must be understood as such. When the human element outweighs the divine, the Church does not flourish. ‘Anthropocentrism’, wrote Bishop Meletios in 2001, ‘kills the Church and its life’.

These are hard words, but words we need to hear, for we live in a self-centred world. I do not mean thereby that our world is wickeder or vainer than before; only, it has so far distanced itself from any notion of transcendence that the only reference available to it in existential matters is subjective.

This is not just a secular trend. We see it in the Church as well. More often than not, it springs from good intentions. I was recently exposed to a new vernacular translation of the liturgical Psalter. The third-person singular male pronoun (‘he’) had been all but eliminated, replaced either by inclusive forms or turned into the second-person ‘you’, as if the text were addressing the person reciting it. You might ask: Is this not admirable, enabling us to overcome gendered bias, allowing all people, women and men, to recognise themselves in the sacred text? Indeed it is, if it is ourselves we seek. For our mothers and fathers in the faith, this was not the case. What they sought in the Psalter was not their own reflection but the image of Christ, our Lord. Through modifications like the one to which I refer, this image is reduced to a faint palimpsest onto which our self-image is imposed.

This casual example is symptomatic of a tendency notable in the life of our Order, too. The past five or six decades have been marked by audacious adaptations. With the wind of Gaudium et spes in its sails, the Order swept into the post-conciliar age. Efforts of adaptation were immense. Much that was fine was produced. Some precious things were cast overboard. Such was the traffic on the sea in those days that one risked being trawled along by corporate momentum, sometimes with only scant attention paid to the Morning Star, which reveals the journey’s end.

Inculturation stood for a different form of adaptation. We think of it as something exotic: the endeavour of missionaries in far-flung areas to learn new languages and customs. This is one aspect, certainly. Exercised deliberately, it can bear rich fruit for good. I wonder, though, if we have been conscious enough of a more insidious inculturation which consists in gradually yielding to the mindset of a world for which ‘God’ has ceased to be a meaningful term? A criterion for discernment has been given us by Mother Cristiana Piccardo, who in 1999 wrote:

The most significant inculturation called for is without doubt that of remaining faithful to our own monastic charism, while listening attentively to what the local Church is telling us. Yes, inculturation does mean attention to the riches of local life and culture. But even more fundamentally it means introducing the newness of the Gospel into local culture as a living, loving leaven.

Among the tools for good works, St Benedict gives us this: ‘Sæculi actibus se facere alienum’, ‘Your way of acting should be different from the world’s way’. Is it?

My own monastic life has been marked by yet another adaptation. Seemingly without interruption, the discourse of renewal in the Order turned into a discourse of precariousness, as when a tune modulates into a different key. The word ‘precariousness’ was our mantra of adaptation for a while. Many received it — such was my impression — as a liberating word. It legitimised the admission of worry and fatigue after long mutual reassurance that everything was going better and better. ‘Precariousness’, though, does not point out a direction to follow; it describes a station on the journey. There is a risk that, instead of carrying on, we settle there, putting our roadmap into the drawer while turning our noviciates into infirmaries.

This attitude easily leads to a fourth adaptation which I’d call adaptation to the charm of sleep. Once, during a visitation, I asked an elderly monk if it worried him that years had passed without a single novice staying. He looked at me astonished, as if my question was self-evidently daft, and said: ‘Why no! It is so lovely and quiet here now; I can focus on my spiritual life.’ Elsewhere, with prospects of closure looming, I have often heard it said, ‘Oh well, as long as I can die here’. At first, the statement touched me. ‘An expression’, I thought, ‘of Cistercian love of place!’ I gradually came to consider it differently. This mindset, generalised, wraps the monastery up in itself. It becomes an almost triumphant monument to awaited extinction, an anticipated mausoleum ostensibly bearing witness to past glory, yet really embodying resignation.

It is often assumed that what puts the Church at odds with contemporary society is its ethical teaching. Many cry out for change in this area. Quite apart from the merit of considering what might be a Catholic response to particular, perhaps new problems in ethics (something each age is called upon to do), I consider the assumption false. I do not think the principal skandalon is ethical. I think it is metaphysical. The holiness of God! The splendour of his glory, made manifest in Christ through infinitely gracious condescension! These core realities, which to the founders of Cîteaux were axiomatic, seem strange to an age whose outlook is wholly horizontal. We are children of that age. Of this we must ever be aware.

Let us stay focused on our founders for a moment. What was their concern? Considering the Rule of St Benedict, they saw before them a sublime, exacting, and lovely standard to which they knew themselves bound. They saw the Rule as the God-given instrument by which they would rise above themselves, begin to acquire the stature of Christ, and offer to God a well-pleasing oblation. They were not carried away by the know-it-all exuberance of youth. Stephen Harding was almost forty, a man of rich experience. He knew what it was both to lose good zeal and to find it again. Robert was seventy-one, a tremendous age in eleventh-century Europe. He had been the superior of three communities. He and his group were driven by an urge to reach ever higher, to give ever more, conscious of their solemn obligation and of God’s sweet promise, which is realised in proportion to our generosity.

By contrast: who, these days, accepts anything as an absolute, binding norm? What Benedict XVI called ‘the dictatorship of relativism’ has, after the manner of dictatorships, reconfigured our minds. We do not conform to standards; we conform standards to ourselves. Instead of rising through arduous effort to transcendent norms, we reduce norms to levels within reach. We use appealing words to describe what we are doing. We talk of being ‘sensible’ and ‘mature’, of exercising ‘freedom’ and ‘responsibility’, of making life more ‘human’. Something in these notions is valid, of course. The net effect, though, risks being a loss of aspiration — and thus of attractiveness. Instead of subsisting within monastic life as within a reality that promises to elevate and transfigure us, we are liable to pitch our tents in the plain, constructing life there in a way that is comfortable, finding in comfort ample compensation for a narrowing of perspective, a reduction of altitude.

I am not trying to moralise. Nor do I lack compassion for communities or individuals that may be tired and discouraged. I know what it is to be tired and discouraged! Tiredness and discouragement have strengthened my conviction: only by re-positing the absolute centrality of the demandingly vertical, theocentric axis in our life will we know revitalisation. We must look away from ourselves, not fall for the temptation to think that a monastery exists for the sake of its community. A monastery is not an end in itself. It is called to be a sign of God’s transcendent beauty and truth in love. ‘Look up, not down’ reads the shortest of the sayings of the Desert Fathers. It is a word for the present moment.

In the light of this word we can read experiences of diminishment, too. A monastery is the material shelter of a group of women or men called to witness to the Kingdom of God in a given place, at a given time, for a given purpose. A community is a living, organic thing. It normally belongs to the nature of organic forms of life to be born, to flourish, to be fruitful, and to die. St Benedict urges: ‘Keep death before your eyes daily’. That reminder pertains to our collective life as well as to our lives as individuals. A quick look through the Atlas of the Cistercian Order suffices to see the vast number of sites on which life flourished for a season, then ceased. Our notion of monasteries as places destined to live for ever is romantic. Our homeland is in heaven. We must sit loosely to dear attachments, even when they stand for spiritual values. ‘What good is it for a nun’, asks the First Prioress in Bernanos’s Dialogues of the Carmelites, ‘to be detached from the world if she is not detached from her detachment?’ What matters is the divine life entrusted to us, the fire in our hearts — for it to be passed on, in whatever place, old or new, it may please God to let it shed its warming light now.

Our Order was born of cataclysmic destruction in an experience of exile. Out of desolation God brought forth new fruitfulness. How? In January I had the joy of visiting Gethsemani. I paused daily before the founders’ cross in the cloister. The first monks brought it with them from Melleray. It bears the inscription: Vive Jésus, vive sa croix! That is to say: ‘May Jesus live in us, through us, here in this place; may his cross reveal itself here a source of life!’ It was the one indispensable piece of luggage the founders needed to start monastic life in what was still a ‘new world’.

Recently I came across a letter from another monk settled in a world ancient in itself but new to him. From Arunachala in India Dom Henri Le Saux wrote it to his sister Thérèse in 1955. He was immersed in a culture that had next to no Christian coordinates. He wished to know the bearers of that culture; yet saw that his primary task would unfold at a level beyond dialogue. He wrote: ‘There is a great need for holy monks in their midst to let them understand the holiness of Christianity’. He added: ‘If you pray hard for me, I may obtain from the Lord the grace to be one of these. The only thing I need, the only thing sincere Hindus require of me, is sanctity.’

As a monk and now a bishop, I am certain that the same imperative is ours. It is the message I wish to convey to you. The Lord lets our lives unfold in a world marked by epic uncertainty and doubt. Our mission is to make of our lives an incarnate sursum corda. May Jesus live in us! May we show forth the vivifying power of his cross! May the example of our Fathers inspire in us deep love for the observance of the Holy Rule that we, like they, may have ‘a passionate desire to commit to successors [our] heavenly-sent treasure of virtues for the salvation of many yet to come’ (Exordium parvum, 1, 16). I pray for the deliberations of the Chapter and assure you of my profound esteem and fraternal affection.

+fr Erik Varden ocso

Bishop of Trondheim