Archive, Conversation with

Conversation with Luke Coppen

You can read the full text of the interview here.

What makes a good Trappist beer?

Perfect balance: that’s the secret. The ingredients are simple. The processes are simple. But they’ve all got to be calibrated. This notion of equilibrium is essential to the monastic life. You find that as a theme in the Benedictine Rule. You find it in St. Anthony [the Great] and many of the sources.

The production of beer is actually quite a good school, of ensuring balance, getting exactly the right proportions, and letting processes take their time. One of the exciting things about artisanal brewing is that there aren’t any added chemicals. You sit around and wait. And you watch and you clean, and you let things take their time. And so you enable the ingredients, which have got to be the best ingredients, to reveal all their potential

St. Paul talks about the twinkling of an eye in which everything will be revealed and we shall enter eternity. We shall look at our lives here on earth in a supernatural flash that will illumine everything and make it appear as a single entity. But when we’re engaged in the daily slog of living, it all seems so slow, and we can’t see how things fit together. That’s fundamentally where we need patience, just to let things work.

We’re a bit like the ingredients in a brewing kettle. We are being made into something the conclusion of which we can’t foresee because it’s in the mind of God. Like the hops and the malt, we are being treated in order that our inner potential be revealed, and enabled to interact with other ingredients to make something which is beautiful and nurturing.

Can that perspective – the wisdom of the brewer – help with Church conflicts?

I think so – to have that ability to look for a broad perspective, to step back, to see the present in the light of eternity, and sometimes just to consent to the fact that here and now I may be going through something which is dark, which I can’t understand, and my chief task is simply to persevere in that darkness for a bit in the hope and in the certain expectation that dawn will rise.

Bishop, what is Christianity?

Christianity fundamentally is faith in – and an existential attachment to – the revelation of Jesus Christ. By which I mean his teaching, but fundamentally his manifestation of man’s call to share in the very life of God, in his victory over death. Fundamentally, Christianity is the certainty that in Christ death has lost its sting. And everything else flows from that.

That was the first kerygma as we encounter it in the New Testament: ‘Christ is risen.’ And from that statement, there are enormous numbers of consequences, more or less simple or complex, that embrace all of existence. But fundamentally, that’s the core of it.

What is prayer?

It’s the lifting up of the heart, to cite that phrase from the dialogue before the Preface of Mass. It is an opening of my being to the reality of God and an engagement of my being with God’s being in a kind of dialogue, which is sometimes an explicit dialogue and sometimes very implicit and mysterious.

I sometimes think that we overcomplicate prayer. I’m sure you’re familiar with the writings of Anthony Bloom. There’s a marvelous story when he goes to an old people’s home and he encounters this old lady who is in a great spiritual crisis because she says she recites the Jesus Prayer day and night and yet she is in this state of spiritual desert.

Metropolitan Anthony listens to all this and says: “May I give you a piece of advice?” And she says: “Of course.” Then he says: “I want you to act on this advice.” And she says: “Yes, of course.” And he says: “From now on, I ask you to spend half an hour a day not saying any prayers, but simply sitting in your chair and knitting in the face of God.”

It totally revolutionized this woman’s spiritual life.

Sometimes, if we could learn just to shut up, and to open ourselves attentively, much of what we think of as our great spiritual crisis might actually be resolved.

Is that what you’d call contemplative prayer?

I’d be wary of summing up contemplative prayer in some sort of slogan. I’d be more inclined to talk about contemplative life. The contemplative life is fundamentally a state of attention.

I’ve been very marked and very helped by a phrase I found years ago in a treatise by the Florentine Renaissance humanist Pico della Mirandola, who speaks of the fundamental vocation of the human being as that of being “universi contemplator.” So to be the one who contemplates the universe, who contemplates the whole.

I’m pretty convinced that man is by nature a contemplative, only he’s got to discover it. To live contemplatively is fundamentally a matter of standing still and paying attention and looking.

There’s a contemplative hidden in everyone?

And not necessarily all that hidden. Right now, in the cultural context which is ours, there’s a lot that militates against the contemplative life because we’re addicted to disturbance. We love to be disturbed. And if we haven’t been disturbed for the last 20 seconds, we find something to disturb us. Part of the soul pain and frustration, and even aggression, that that experience can release in people is an indication that, fundamentally, we’re constructed for a different mode of interacting with the world.

Blaise Pascal said that ‘all of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.’

There’s such wisdom in that. You find the same insight in the early monastic tradition, the Desert Fathers. One abbot said to his disciple: “Remain faithful to your cell, and your cell will teach you everything.”

Does the Church still have a need for contemplatives?

An urgent need, because the heart of the Church is a contemplative heart. We need that constant refocusing of our sight, of our mind, of our heart upon the mystery of God, in its eternity and its constant newness. It’s crucial that there are people who by profession assume that task full time on behalf of the whole Church. But that doesn’t excuse the rest of us from also aspiring to a contemplative attitude, outlook, and practice.

Bishop Varden, has religious life collapsed in the West?

I’m not sure you can say that it has collapsed. Again, it’s important to see this in a long perspective. When you look at 2,000 years of Christian history, there have been highs and lows and there have been periods of growth and great vitality, and there have been periods of a certain decadence and great poverty. So I don’t think we should get too excited about our particular problems now.

Fair enough, many communities have lower recruitment. We’ve seen a number of closures of religious communities and congregations, and I dare say we shall see more. But at the same time, we see communities that are flourishing, new forms of consecrated life being born. perhaps on a more modest scale, but nonetheless. The imperative and the challenge of the monastic life are so fundamental to the Christian calling that it will never vanish. It will go through times of metamorphosis, but it’ll always come back again and re-flourish.

Are people less spiritual today than in the past?

They are every bit as spiritually sensitive, only they’ve largely lost the conceptual tools to make sense of that spiritual sensitivity. That’s a source of great pain to a lot of people. I would, as a Christian, posit that the human being is a spiritual being, that when the human being no longer has the language in which to articulate spiritual aspirations, longings, sufferings even, then these become implicit and subterranean. They take other forms and can’t be recognized for what they are and result in frustration. The sensitivity is the same, but our capacity to express that sensitivity has largely gone. And that’s a serious matter.

Is it possible to make spiritual progress without the Church? Can I overcome my ego by mindfulness and other practices?

Certainly, but I suppose the question is whether overcoming one’s ego would count as spiritual progress. In the strict sense, defining the terms in a Christian way, the spiritual life is life in the Spirit.

The Spirit is at work throughout the world. That’s something Christians have always known. And the Spirit is at work even when he isn’t recognized.

But in order to make really oriented progress, to move towards a definitive aim, I need to know what that aim is. I need to know what the goal is I’m moving towards. So, yes, there is a certain spiritual awakening and growth which is possible outside the Church, but for that spiritual growth to reach fulfillment, I’d say the graces and support that the Church provides would be necessary.

Does the Church’s communal dimension help us to make progress?

Absolutely. One of the passages from the Wisdom books that was really beloved to the Cistercian fathers is a verse that goes: “Woe to him who is alone because he has no one to raise him up when he falls.” In that line, the Cistercians saw the monastic community in a nutshell. And you could also see the ecclesial community in a nutshell. What a grace that is to be walking alongside other people who will give me a hand when I need one, and to whom I can also extend a hand when they stumble.

Let’s talk about Norway. We sometimes read that the Church is growing explosively in Norway. Is that accurate?

No, it’s not growing explosively. There’s been quite a fast incremental growth over the last 15-20 years, mainly through immigration from Poland and Lithuania. That wave has reached a plateau. I wouldn’t dare to prognosticate too far as to future trends, but certainly there is a great vitality in the Church. I ascertain that as someone who has lived abroad for 30 years.

When I was appointed bishop here, I came into a reality which I didn’t really know at all. So I had to discover it. I’ve been struck by and heartened by the positive energy, the goodwill, the faithfulness, and the extreme diversity of Catholic life in this place, Even in the Prelature of Trondheim, which is geographically large – it stretches over 55,000 square kilometers – but demographically smaller, about 18,000 Catholics, those 18,000 Catholics come from about 130 countries.

What makes Norwegian Catholicism different from Catholicism in other countries?

In some ways, I’d say that Norwegian Catholicism is still finding its feet. Culturally and sociologically, it’s an interesting situation, because the number of Catholics who are ethnically and culturally Norwegian is very small. That can be a bit of a challenge, but it’s also a great enrichment, because it does necessitate a constant reference to what is really Catholic, in the sense of what is universal. That would be one aspect of Catholicism in Norway that is very clear: a profound connection with the universal Church and a gratefulness to be part of that large communion.

What relationship does Norway have to its pre-Reformation Catholic history?

The situation here is very different to England because there was no Norwegian recusancy. There was a complete break, an enforced break. Rather like in England, there’s been some carefully revisionist scholarship by historians of all confessions and none that has shown pretty unequivocally that there was a great resistance to the Reformation here. But it was imposed by royal diktat, and because the population was so small, it wasn’t all that difficult to supervise. There was no continuation of Catholic sacramental life.

A number of Catholic customs continued and went underground – and that too is very interesting: how pilgrimages to certain shrines continued. The cult of St. Olav as well: that has remained deep in the national psyche at some level. It has enjoyed a great revival over the last century, and it is striking that the feast of St. Olav, on July 29, has become a real pilgrim festival. Lots of people walk the old pilgrim routes. That emphasizes the connection with a medieval Christian patrimony.

Within the Lutheran church, it has generated a degree of perplexity because people come pilgrimaging to the tomb of St. Olav, and that can be problematic if you haven’t really got the vocabulary to speak of the place of saints within the eternal communion of the Church. So that’s ongoing work at the moment. But there’s certainly a great openness also in the Lutheran church to embrace this movement.

Why is Trondheim called a territorial prelature, rather than a diocese?

I had to Google this when I was appointed to find out what it meant. Traditionally, a territorial prelature was a diocese in mission territory, so a diocese in the state of becoming — It was part of the process of development. I’m not entirely sure why the nomenclature has remained as it is. But I can’t say that that’s a great concern to me.

Trondheim didn’t have a bishop for 10 years until your appointment.

It was a long wait. One of the things I’ve been very struck by, and humbled by, is how happy people are to have a bishop again. You can abstract from who that bishop is and what his strengths and weaknesses are, but that there is someone there who represents that personal bond of this local Church with the universal Church and who embodies that… A bishop’s primary task basically is to sit on his chair, his cathedra, and embody that link.

What about you? Why do you think God called you to be a bishop?

Now that is a question I can’t answer. That pertains to my particular mystery of faith. It remains profoundly mysterious to me.

Is being a bishop compatible with being a Trappist?

I wouldn’t say they’re easily compatible, but I wouldn’t say they’re incompatible. I’ve given this a lot of thought over the past couple of years, as you can imagine. In antiquity, it was not uncommon for monks to become bishops and it wasn’t all that uncommon in the Middle Ages. And in the Eastern Churches, it’s systematic. All the bishops are monks.

I’ve also reflected on that in the context of the Holy Father’s continued reminders to bishops that they’re not primarily administrators and pen-pushers. There’s a responsory in the breviary – it’s the Common of Pastors, I think – that speaks of the pastor as being someone who “prays much for the people.” That is a great inspiration to me and a great reminder that one of the most important things that a bishop does is to pray, to carry in prayer the work and the people entrusted to him.

To maintain that absolute priority of the supernatural in one’s own life is a prerequisite for being able to do anything of value in the more pragmatic sphere.

How do you maintain that prayer life?

One good thing to aim for is to have a basic structure to the day and to make sure that you really carve out time for prayer, for serious reading, for just being still and listening. At the same time, one needs great flexibility.

That too is something which is fundamental to monasticism. It says in the Rule of St. Benedict that the monastery is never without guests. Benedict doesn’t say it’s important that monasteries exercise the ministry of hospitality. He simply states as a matter of fact the monastery never lacks guests. And it’s true: people turn up for all sorts of reasons, announced and unannounced.

It’s striking that he says that every guest that comes should be received as if he were Christ. That too is a basic dimension of attentiveness and openness in life: to be fully engaged in what is going on around me now and to receive even the seeming distractions that present themselves as possible promptings from Providence. To keep asking “Where is the Lord in this?” or “What message is this person or this circumstance carrying?” That’s a form of contemplative living in the midst of distraction.

In some monasteries I know there’s a bell contraption in choir, so that when someone comes to the door, there’s someone who’s assigned to attend to them. It’s got to be kept in balance and you’ve got to keep yourself from useless distractions. But at the same time, sometimes stepping out of the protective enclosure of what I might think of as “my spiritual life” is in itself a spiritual exercise that I may be called to. And there’s always the primacy of charity.

You’ve studied the Syriac language quite seriously. What drew you to study Syriac?

I’ve long been interested in Semitic languages. I find that linguistically they’re interesting. What drew me particularly to Syriac was the discovery of Ephraim the Syrian and then the discovery of this great Christian patrimony, about which at that time I knew very little.

And then the gradual realization, which is blindingly obvious once the penny drops, that Christianity is an oriental religion. We so easily assume that it’s German or English. Well, it isn’t.

Syriac is a dialect of Aramaic. It was the dialect that was spoken and written in Edessa, now in Turkey, which was a great center of Syriac civilization, which is why it became a normative and literary form of Aramaic. But in learning the Syriac language, you come as close as it’s possible to get to the words actually spoken by Christ and His disciples.

The Gospel has come down to us in Greek, but the primary text we have – the Greek text – is already a translation. To be a Christian, to engage with Scripture, is by definition to be involved in a process of translation. And it’s good to be sensitized to the Semitic origins of that revelation, to have some sense of what the language sounds like, what it feels like, the things it can easily express, the things it can less easily express.

To me, that was absolutely tantalizing and fascinating, to find myself brought to the wellspring of revelation. Plus, there’s just such a marvelous treasury of riches in that tradition. It’s extraordinary.

What did you take away from your study of Gregorian chant?

I first was mindful of Gregorian chant when I was 12 or 13. I listened to a lot of music and I’d bought a recording of a Mozart Vespers. Mozart’s music was interspersed with some Gregorian antiphons, and I remember that there was the Benedicamus Domino at the end of Vespers – the bog standard Benedicamus Domino which to this day we sing at Vespers on Sundays, which goes like this [sings]: “Benedicamus Domino.” And I listened to that and I thought: What was that? And I listened to it again and again and again and again. I was just keen to learn more about this.

Then a few years later, when I got to Cambridge, I got involved in the chaplaincy there and there was a good Gregorian Scola. I joined that and then one thing led to another.

Is Gregorian chant neglected in the Church today?

I definitely don’t think we’re making the most of it. But I don’t think we’ve ever made the most of it. Think of Dom Guéranger and Solesmes, and that whole movement. They were basically unearthing it from centuries of neglect. It’s not as though there’s been some great seamless continuum.

We’re quite privileged because we have excellent books at our disposal. We really have all the music and the resources we need. But Gregorian chant is an austere form of music and it requires quite a lot of training, both for the ear and for the voice. And it requires a certain insight – and patience again – to enter into that acoustic universe. And quite often that patience is lacking.

But the people who’ve had some sense of entering that universe will almost unfailingly be spellbound by it because there is such a depth of interiority and a beauty of poverty almost, because Gregorian chant uses such simple means to carry and convey the text. Fundamentally, it’s not just a body of pretty music. It’s a proclamation of the inspired word of Scripture. I’ve always been very interested in what I like to think of as the kerygmatic aspect of Gregorian chant, that even the simplest antiphon is a little sermon in sound.

Why is liturgy such a battleground in the 21st-century Church?

Because it touches all of us intimately. And also because the liturgy brings us together and calls on us to participate, to some extent, in the performance of a rite, in that we all have our parts to play. It calls on us to submit personal preference to a common plan. That is always difficult in any context, because I want to do my thing.

That’s one reason why it’s such a hot potato. Another is that it’s a historical fact that over the last 60-70 years, we’ve just lived in such an experimental universe, with so many various, and quite often incompatible, notions of liturgy being bandied about that our nerves are a bit frayed. There’s almost an atmosphere of anxiety, which to some Catholics has come to seem constitutional. I don’t think it needs to be.

What matters, as always, is to go deep. In terms of the history, to which we now are the heirs, the time has come to look dispassionately with appreciation, but also with a critical eye, on some of the accomplishments of the past decades and to ask: what is an enrichment and what isn’t?

What really matters is to root oneself again and again, and evermore firmly, at the salvific core of the liturgy, to remember that we are not the subjects of the liturgy. It is fundamentally Christ who is the subject of the liturgy. We engage in it as a way of communing with Him and to touch the unfolding of the redemption of humankind. That’s what matters: to keep that rootedness clear.

Why are we also clashing over tradition today?

We mustn’t think of tradition as some sort of package tied up in string. “Tradition” is a dynamic noun that refers to a process. What matters above all is to find my place within that living transmission and to become a link in that chain and to be pleased and humbly grateful to receive what is being passed on to me, and pleased and humbly grateful as well to be able to pass that on – and to make sure that what is passed on isn’t less than what I received.

We must guard against the seductions of facile polemics and dare to be countercultural in as much as we don’t cede to that need to be angry all the time, because that’s just boring and a waste of energy.

Is anger a dominant emotion of all of our time?

I’m not sure if it’s a dominant emotion, but it’s a prevalent emotion. We live in extremely anxious times. When one thinks of the war in Ukraine, the economy, cultural collapse, environmental threats, so many people feel that they are caught up in these deterministic processes which are entirely beyond their control. One way of exercising and affirming subjectivity is anger.

It’s too much to be angry at the cosmos. We choose our own little pockets, where we feel we have a degree of mastery or where we feel that our voice may plausibly be heard, and then we just pour out all our anger there. That is a bit of a cultural trend.

Does the Church offer a route out of that?

Yes. It’s one of the readings at Compline, which recurs in the Roman Office every Wednesday. And it’s the line from Ephesians: “Do not let the sun go down on your anger.” That is, deal with it.

That’s something I see as a pastor as well – and simply as a human being – that arrested or blocked or unacknowledged anger can be a huge factor in many people’s lives. It’s as well to humbly acknowledge the anger I carry in me and then to ask, “Well, what can I do about it?” rather than just letting it fester. It can be a matter of asking forgiveness as well. That’s a Christian practice that we should be assiduous in realizing.

Sometimes it’s useful to have – as the monastic tradition presupposes – a spiritual father or spiritual mother, someone I trust and whose discernment I trust to whom I can simply speak what goes inside me. And I can put into words sometimes inchoate and vague notions that swim around my consciousness and see what is what, and then formulate a reasoned and prudent response.

You took a leave of absence before you were ordained a bishop , suffering an illness that was brought on by ‘great fatigue’ Have you recovered from that period?

Yes, I think so. In retrospect, I consider that an immense blessing. It was simply a matter of a brother donkey saying: “Stop.” There was also something of an existential shock at the deep change required by the nomination. It just released an accumulated tiredness, because we’d been setting up the brewery and all that. It had been an intense time.

But I am so grateful that I was given that opportunity to just step back, to be quiet, to wait upon the Lord – to acknowledge all my own limitations as well and be properly regrounded in essentials.

Another thing which I found profoundly touching is the fact that I was really prayed into the diocese because the people – who here are very good – they really took on this intention and they did pray for me. I consider myself immensely fortunate to have been prayed into the diocese.

Who’s your favorite saint?

Who’s your favorite saint?

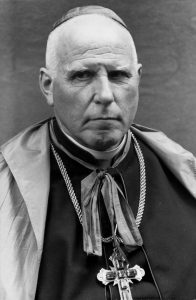

That’s like asking: “Who’s your favorite friend?” I happened to be in Münster last week in Germany. I went to a museum that had an exhibition that was dedicated to Cardinal August von Galen, who was beatified not all that long ago. I’m going to keep his portrait on my desk for the foreseeable future. For the courage that that man embodied in rising up to what was an extremely vicious, absolute, and seemingly all-powerful dictatorship and saying: “No.”

I’ve also been inspired, and helped really by his episcopal motto, which was “Nec laudibus, nec timore” – neither for the praise of men nor for fear of men.

I read last year the autobiography of Josef Pieper, who was from Münster and who knew von Galen. He makes the point that there wasn’t really anything in the years leading up to the war that would set him apart as a great prophetic figure. But he is simply an instance of a human being with a conscience and with the intelligence of his conscience. A man who has that capacity to say: “Enough. Thus far and no further.” And that is profoundly impressive and inspiring.