Archive, Articles

Cum Davide versari: The Psalter as Acquired Self-Expression

This paper, given at a seminar in Rome, was published in the volume A Book of Psalms from Eleventh-Century Byzantium: The Complex of Texts and Images in Vat. Gr. 752, ed. by Barbara Crostini and Glenn Peters (Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (Studi e testi 504), 2016). I reproduce it here with the kind permission of the editors.

Among the victims of the pestilence that raged in Constantinople in 741 were a young couple of comfortable standing called Sergios and Euphemia. Their death left three orphaned children, two daughters and a son, to be raised by relatives. On the education of the boy, Plato, all care was lavished, and he could make a precocious career as a civil servant. The girls were trained rather in domestic accomplishments apt to make them attractive to husbands, and unburdened with bookish learning. The one sister, Theoctista, about whom we are well informed entered the married state without being able to read. She had to teach herself, therefore, and could often be found burning the midnight oil deciphering writing. If we ask why, at the end if a long day, she bothered, the answer is clear: she wanted to learn to read because she wished to recite the Psalter. From that time onwards, her son tells us, οὐκ ἐπαύσατο ὁμιλοῦσα τῷ θείῳ Δαυὶδ; or in the translation of Jacques Sirmon, ‘nunquam destitit cum Davide versari’. Charles Diehl was possibly speaking tongue in cheek when he maintained, in his portrait of Theoctista, the valiant mother of Theodore Studite, that her biography is broadly representative of women of her class in that age. What we know of Theoctista makes her appear in most respects untypical! The style of her devotion, though, was certainly traditional, and that is what interests us here, as we ask questions about the significance and status of the Psalter in medieval Byzantium. Long before she could start thinking about embracing monastic life, while her children were small and she had a large house to run, Theoctista nurtured her devout heart by ‘conversing with David’. What sort of conversation are we talking about? Why was it so important to her? I propose to address these questions with reference to a venerable Patristic authority before considering how our particular Psalter might illumine us.

Theory

In Vaticanus Graecus 752, the Letter to Marcellinus is copied out between a pictorial cycle of the life of David and another of the life of Christ, both of which precede the Psalter proper. It is appropriate that Athanasius’s epistle should be sandwiched between digests of these two extraordinary destinies, of David and the Son of David, since his disquisition is concerned to show how each presupposes and mysteriously contains the other. Marcellinus had turned to Athanasius for help because he wished to understand the sense, the νοῦς, of each Psalm; he wanted to see how the Psalms were ‘minded’. Athanasius obliged, not by a series of individual commentaries, but by providing a key to the Psalter as such, a master key fit to open the gate of understanding even when, in its wanderings, the mind happens upon seemingly insuperable obstacles.

I am not being irresponsible in using this kind of spatial imagery, for Athanasius fully endorses it. While other books of Scripture, he says, deals separately with specific aspects of revelation, the Book of Psalms is ὡς παράδεισος τὰ [τῶν πάντων] ἐν αὐτῇ φέρουσα μελῳδεῖ. It is like a garden. With melody it bears all the fruits we can find in other books of the Bible while, by singing, it shows forth things uniquely its own, too (c. 2). To move within the Psalter is to enjoy a panorama that displays every aspect of salvation history at once. The Psalter does not only commemorate these events. It enacts them and makes them present. Thus we do not merely contemplate the fruit of the garden; we do not merely celebrate it in song. We pick it and eat of it as we have need (c. 30). This is where the Psalter comes into its own and reveals its specificity. The Psalter is ours more than any other book of the Bible. By a special grace it engages – or envelops – the praying subject in such a way that the παράδεισος he enters through psalmody seems to him not someone else’s but his own. When reading other inspired books, says Athanasius, we admire the words. We repeat them with awe, conscious of our unworthiness to claim the statements of Moses, say, or the Prophets as our own. With the Psalms it is different. One who reads them with faith reads them as ‘his own words’ (c. 11). His ‘conversation with David’ is not restricted to listening or recitation. He appropriates David’s words as being about himself. If we want to understand the privileged position of the Psalms in Christian worship, we must follow the reasoning behind this remarkable claim.

For it is remarkable, an ἴδιον θαῦμα, that the Psalter puts ‘the movements of each individual soul, the ways in which it changes and the means it needs to correct itself’, into words (c. 11). It is not just that we read the Psalter; the Psalter also reads us, revealing us to ourselves. We are at once subject and object, yet the exercise does not descend into mere introspection, in as much as we are not on our own in the garden into which we are transported. In this singular space, the constraints of time and space are cancelled. The mystery of salvation is present simultaneously and in totality, casting light on us who enter and soliciting our response. Athanasius uses a suggestive phrase to describe what is going on. Each reader, he says, will find that the Psalter articulates the movements of his own soul, his joys and sorrows, his praise and penitence. The recognition that ensues operates a kind of fellowship with the experience out of which each Psalm arose. And so the Psalter enables us to seize the ‘the image’ that informs the words we recite: δύναται πάλιν ἐκ ταύτης ἔχεσθαι τὴν εἰκόνα τῶν λόγων (c. 10).

I need hardly point out that the effort to define the proper relationship between word and image in worship occasioned intense controversy in the Greek Church over many centuries, and that it involved more than just the status of pictures. Quite what is presupposed by the passage from the words of a sacred text to the icon of those words will have been explained in different ways by Athanasius and by a learned clerk in the age of Theoctista. It will have evoked a different response still by the scribe who transcribed the Letter to Marcellinus in our eleventh-century psalter. This much, though, will surely have been conceded by all three: that the iconic potential of the Psalter consists in its ability to make the salvific mystery tangible and accessible. It translates us who read from the realm of discourse to the realm of experience. Words are useful for admonition and instruction. Communion with an image, on the other hand, is apt to confer an experience of participation. It is thus interesting to hear Athanasius say that the Psalter ’provides the image, somehow, for the course of the life of souls’ (c. 14). He is speaking in the first place of an image of life as it should be, for the Psalms tell us how we ought to live, speak and pray (c. 11). But he is also speaking of an image – a sometimes disturbing image – of life as it is. ’It seems to me’, says Athanasius, ’that [the words of the Psalms] are like a mirror to the one who prays them, letting him contemplate himself and the movements of his soul in them’ (c. 12). The occasional violence of the Psalter, so disconcerting to the uninitiated, here reveals its true, most profound significance: the transgressor no less than the keeper of the Law recognises himself in this book, ’for the Psalms contain the deeds of both’ (c. 11). Whatever our state of spiritual progress, these texts provide τύποι καὶ χαρακτῆρες, types and impressions, that correspond to our reality (c. 12).

All of Scripture is inspired (c. 2). In all of Scripture the Lord is present (c. 33). About this, the Letter to Marcellinus is quite clear. What distinguishes the Psalter is first of all its density of expression. In restricted space it narrates creation’s history and destiny. It provides a chronicle of Israel; a celebration of the Law; an exploration of the human heart; an anthology of glory. Athanasius maintains that, in it, ‘the whole of human existence, both the dispositions of the soul and the movements of the thoughts, have been measured out and encompassed. There is nothing beyond these to be found among men’ (c. 30). A second hallmark of the Psalter is the rehearsal of this range of experience in terms of a single destiny. The progressive ‘Davidisation’ of the Psalms, which occurred over centuries, enabled a confluence of perspective whereby the history of salvation could be celebrated in its universal aspect and at the same time applied to a personal biography. It was an approach that paved the way for the New Testament’s typological use of the Psalter to interpret Christ, drawing on Jesus’s own references and his post-resurrection assertion that the Psalms speak ‘about me’ (Luke 24:44). The apostolic Church followed on in developing its ministry in the light of the Psalms (Acts 1:20).

By Athanasius’s day, the christological dimension of the Psalter was brought out in the liturgy, and this is where a pious matron like Theoctista will, four centuries later, have taken their symbolic charge for granted, certain that liturgical reading enables the corporate search for Christ in the Psalms while also making it possible for us to find ourselves in them, through him. There are, then, three protagonists in the Psalter. There is David, who, as the Everyman of medieval drama, represents the human condition. There is Christ, who, in a veiled way, is presaged by David’s aspirations and prophecies. And there is me, the reader, invited to perform the sublime drama of the Psalter as if it were mine. It follows that a ‘conversation with David’ is no mere parroting of old formulae. It is a performative encounter. The ‘image’ it carries spells and bestows ‘presence’.

Application

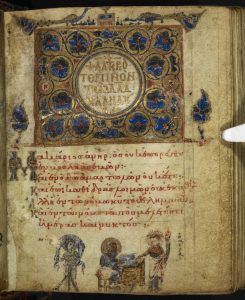

A remarkable thing about the 752 is that it effectively renders the sort of ‘image’ Athanasius was talking about as an absolute, abstract notion into images. With elegant intelligence, it frequently illustrates Athanasius’s principles of exegesis by means of visual commentaries. We are concerned here with the confluence of subjectivities – David’s, Christ’s and mine – in an image that transcends words. We have seen how difficult it is to articulate this overlap, and so it will be worthwhile to consider how it might be rendered iconographically. Let us begin by recalling how the Letter to Marcellinus is itself tellingly framed. In the sections that precede it (containing Paschal tables, Pseudo-Chrysostom’s πρόγραμμα and the preface of ‘John and Theodoret’), we find a series of lovely, sometimes playful, scenes from the life of David. [Folio 2 recto.] The illustrator’s concern is to position David within the spiritual and historical reality of the Old Testament. Explicit reference is made to Moses, who represents Israel’s patrimony, while the figures of Asaph and Jeduthun remind us that David’s praise and prophecy had, from the outset, an ecclesial dimension: his songs were sung with and for the wider community. In this first section of the psalter, the presence of Christ is only hinted at. Three miniatures on the First Folio, depicting David’s birth, bathing, and presentation, are, as Ernest de Wald notes, a typological foreshadowing of the nativity of Christ. There is a further prophetic reference in the cross David holds as he accompanies the Ark on its entry into Jerusalem. It tells us that the songs of David celebrate the promise of redemptive intervention contained in the Old Law. (Folio 7 recto.)

Immediately after Athanasius’s letter, we pass from types and shadows to an explicit proclamation of God’s saving work in Christ. For being badly damaged, the illustrations on Folios Seventeen Verso and Eighteen Recto display the biography of the Saviour in highlights that almost add up to the Dodekaheorton soon to be canonised in Byzantine liturgical art as a catechetical concentrate. This vision of Christ in his mysteries coincides with the ‘divinest thoughts’ promised by the dedicatory poem ‘to those who perceive, as they chant the psalm, the liturgy of the spirit’. Only such vision will equip us to appreciate the full import of the preface miniature to the psalter proper [Folio 18 verso]. Here, within the bounds of a single composition, the depth and breadth of the Psalter are displayed. David, king and priest, stands solemnly robed within a ciborium that heralds the church-structure evidenced throughout the manuscript. Immediately above David, within the field of the horseshoe arch, is Christ enthroned, holding the book of the New Law with his left hand and blessing the spectator with his right. The spandrils to the left and right of the Saviour show us how David’s song is oriented towards the culmination of divine philanthropy in the death and resurrection of Christ. Christ’s Pasch entails the end of death’s reign for all humankind, represented by Lazarus. The pair of prophets indicates the modality by which the two levels of agency are linked, while the musicians invite us, as readers, to put our own psalteries, harps and castanets to good use. As we look around to find our own place, though, we should not think ourselves confined to the margins of the picture. The exposition of Athanasius emboldens us to claim the central position in David’s stead, ‘in medio ecclesiae’. There we can own the Psalter’s praise as ours, fortified by Easter faith and with eyes raised to behold the Lord in glory.

Our manuscript uses a number of eisegetical devices to read the reader into the text. I shall confine myself to a brief analysis of two such, in the successive illustrations to Psalms 11 and 12: two panels that in many ways complement one another. Let us begin with the four-tiered illustration on Folio 42 verso that accompanies Psalm 11. The illuminator’s choice of subject is informed by the superscription in the LXX Psalter, which classifies the text as being εἰς τὸ τέλος, ὑπὲρ τῆς ογδόης. In conformity with the tradition of patristic exegesis, he interprets the reference to an ‘eighth’ not pragmatically, in terms of liturgical rubrics, but anagogically, recognising it as a prophecy of the eighth day, the day of Christ’s judgement. The approach, once adopted, seems corroborated by the subject of the Psalm. It is concerned with the Lord’s ‘scattering deceitful tongues’ as he vindicates other, pure, divine words ‘tried by fire’. The stakes involved are shown in a symmetrical arrangement of four scenes, two drawn from Scripture, two from the liturgy. The uppermost representation of the parousia is instantly recognisable, with Christ riding on the clouds of heaven, surrounded by cherubim and seraphim. The two groups of hierarchs below intercede for the sake of the Church. Uppermost in the second half we see the reward held out to the just as they are summoned to sweet repose in the bosom of Abraham. Apostles and martyrs greet this beatitude underneath. The cherub at the garden gate, meanwhile, hints at a more ominous presence. He is posted there to exclude those who, on being weighed, have been found wanting and are condemned to remain excluded in perpetual darkness. The believer who adopts this message as a key to the Psalm will be alert to the extreme seriousness of the words he utters: ‘Save me, O Lord!’ The sacred text calls on him, here and now, to take sides either with the ‘lips of deceit’ or with the ‘words purified by fire’. The παράδεισος of the Psalter is a testing ground that shows whether he qualifies to enter the παράδεισος of Abraham, whether, that is, he will stand to the right or to the left of the flaming sword.

The hope for paradise regained is still more emphatically evident in the following illustrations, going with the text of Psalm 12 [Folios 44 recto & 45 recto]. The commentators who are our psalter’s chief authorities give due attention to the ἀποστροφή τοῦ προσώπου, the turning away of the Lord’s face, and the pathos of the ἕως πότε with which David begins the Psalm. John Chrysostom stresses the pedagogy implicit in dereliction. The spiritual suffering it induces is intended, he says, as a wake-up call for the sinners, spurring them on to repentance. David is the paradigm that should inform every sinner’s response. Have you sinned?, asks Chrysostom. ‘David is your teacher. […] Do not fall asleep in sin but rise; be mindful at once that God has turned his face away from you, that he has forgotten you’. The grief that ensues cannot but cause an amendment of manners and the restoration of hope. We have here a traditional tropological reading, illustrated by two miniatures (one preceding, the other following the Psalm) that show David prostrate at the feet of Christ. In the first, David lies with eyes downcast before the Lord who sits immobile on his judgement seat; in the second, the penitent king tentatively raises his gaze to look towards Christ, who is now coming walking towards him. The Psalm’s plea for mercy has evidently been heeded. The text, however, has more to offer, and the illustrator shows us what in the composite miniature on Folio 44 verso. It tells us that David’s prayer concerns more than just his particular, personal sin, for here are Adam and Eve raising suppliant hands to heaven beside the cave in which personified Hades clutches their progeny, the whole human race, in a morbid embrace. The initial ‘How long?’ is thus interpreted in the light of a phrase that occurs later in the Psalm, μήποτε ὑπνώσω εἰς θάνατον, ‘lest I fall asleep in death’, and so the fundamental scandal of the human condition, physical death, enters centre stage. The lyrical lament of Adam barred from paradise, conscious of having forfeited the immortality for which he was called into being, was a genre that entered Greek liturgical poetry in the fifth century. It gained a prominent position in the Church’s celebration of Lent. In the picture before us, this liturgical topos synthetically invokes St Paul’s juxtaposition of the First and the Second Adam. Its implications are worked out in the lower panel. The single representative figure from the cave above is diversified into a community of persons, ‘the dead’, reads the legend, ‘who will rise in Christ’. David’s words, then, are Adam’s. Adam’s words are those of the lump of humankind. And this general utterance is invested with new, eternal potency when spoken in the living communion of the Church. It becomes the particular, original profession of any believer who takes it upon himself, in Christ, to ‘converse with David’.

Conclusion

The illustrations of Vaticans Graecus 752 were painted in the century that gave us the mosaic cycles of Daphne and Hosios Loukas, magnificent creations of art and theology that render the mystery of salvation densely present in a new kind of space, pressing the beholder to take in everything at once: Christ on the Cross and Christ in glory; this vale of tears and the glory of heaven. Old Testament patriarchs, New Testament apostles, contemporary monks, and hierarchs of all times stand side by side, flanked by angels, to tell us something about the power of the Church’s liturgy. It enables synchronicity, yes, but really it transcends the category of time. When the Church gathers in prayer, Adam and David, Athanasius and Theoctista pray together with one voice, which is Christ’s voice. I am conscious that I have so far said little that is not blindingly obvious. Our enquiry will not have been time wasted, however, if I have been able to bring home this one, crucial point: that a clerk picking up the 752 in the eleventh century will scarcely have done so with less reverence than he would have felt on stepping inside the church of Hosios Loukas. He will have entered the παράδεισος of the Psalter as an ἐκκλήσια, a living gathering. He will have approached the Psalter as a place of encounter, a sacrament of Christ, and I permit myself to make that point not only as a student of ancient texts but as someone who, like our scribe, is vowed to recite the Psalms again and again every day of his life, with the conviction that it is not a futile enterprise. It is well not to forget this supernatural and (let us risk the word) existential dimension if we wish to understand the response solicited by this remarkable manuscript, which is not only a work of art or a subtle political manifesto or an exercise in exegetical acrobatics, but a profession of faith. It is in order to keep that door open that I suggest it might be useful, in the course of this learned exchange, to cast our mind’s eye back, now and again, to Theoctista’s atrium, where this once illiterate Constantinopolitan matron risked her eyesight sitting up late, darning in hand, conversing with David. His transmitted words, she found, gave voice to the otherwise ineffable sentiments of her own heart. They made up her garden of predilection, the garden in which she would live, die, and hope to rise again.

A digital version of the Vat. Gr. 752 is available here and here.

References: Theodore Studite, Laudatio funebris in matrem suam, n. 3, PG XCIX, 885; Charles Diehl, Figures byzantines, 2 vols (Paris: Colin, 1906), I, 112; Ep. Mar. 1, PG 27, 12. Further references will be given in the text, indicating the paragraph of the Letter; Jean-Luc Vesco, Le Psautier de David, 2 vols. (Paris: Cerf, 2006); Ernest T. de Wald, The Illustrations in the Manuscripts of the Septuagint, III, ‘Psalms and Odes, Part 2: Vaticanus Graecus 752’ (Princeton: Princeton University Press; London: Oxford University Press; The Hague: Nijhoff, 1942), xii.