Archive, Readings

Desert Fathers 34

You can find this episode in video format here – a dedicated page – and pick it up in audio wherever you listen to podcasts. On YouTube, the full range of episodes can be found here.

[Blessed Syncletica said:] Should we be troubled by illness, let us not be downcast if, because of illness or our stricken body, we cannot stand upright praying or sing Psalms aloud. All these things were given us in order to accomplish the purification of our desires. Fasting and sleeping on the floor were prescribed for us on account of [the attractions of] shameful pleasures. If sickness blunts these, the exercises turn out to be superfluous. Why do I say superfluous? Because our destructive tendencies are calmed by sickness as if by a greater, more powerful remedy. This is the really great ascesis: to hold out patiently in sickness and to bring forth hymns of thanksgiving to the Almighty. Is eye-sight taken from us? Let us not be weighed down. We may lose the physical organs of greed, but with our inward eyes we see the glory of the Lord as in a mirror. Are we turning deaf? Let us give thanks that we are made inaccessible, once for all, to vain chatter. Are our hands limp? Our inward hands are no less well prepared for battle against the enemy. Is our body fully in the grip of exhaustion? The inner man will know an increase of good health.

In Butler’s Lives of the Saints, the career of Amma Syncletica is summarised concisely. We are told that she gave herself to God at a young age; that she joined a community where she was in demand as a spiritual mother and guide; then that ‘she foretold her own death, which took place about 400, when she was eighty, after terrible sufferings, born with exemplary patience.’ The oldest source of the story of her life, a text long wrongly attributed to Athanasius, is more specific about Syncletica’s old age. It tells us that she suffered for three and half years from a horrible degenerative disease, possibly some kind of cancer for which there was no cure. It seems worthwhile to mention this aspect of her biography, for it lets us see that when Syncletica spoke of illness, she spoke of what she knew. It is easy, and strangely alluring, to hold forth on the stature of physical pain when one has not known it much, but such discourse sounds hollow. The saying before us, by contrast, is dense.

To be a spiritual champion freely embracing hardships, deprivations, vigils, and fasts engages our noble aspirations. A Psalm of David begins with the cry: ‘Blessed be the Lord, my rock, who trains my hands for war, my fingers for battle.’ In St Benedict’s arrangement of the Psalter, laid down in the Rule, this Psalm is sung at vespers on a Friday, the day on which we commemorate Christ’s Passion. A line is drawn between the Lord’s sacrifice and the monk’s ascetic battle, inspiring a powerful sense of purpose and a noble pride in being conscripted for service.

This is a good, formative experience, yet does not spell full configuration to Jesus’s oblation, for our ego remains engaged, channeling our energies profitably while enjoying a degree of satisfaction. It is a joyful thing to pour oneself out freely for love. The chances are, then, that a time will come when we receive a call like the one addressed to Peter on the shore of the Sea of Tiberias: ‘Truly, truly, I say to you, when you were young, you girded yourself and walked where you would; but when you are old, you will stretch out your hands, and another will gird you and carry you where you do not wish to go’. Will we then follow trustfully, still generous and loving, or will we rebel? The encounter with sickness or imposed constraints may reveal that we were not as advanced in discipleship as we had assumed.

Amma Syncletica stresses the nature of ascetic practice as a means to an end. It is important to keep this distinction in mind. The point of monastic life is not interrupted sleep, scarce eating, or long hours of Psalmody. The point is acquisition through Christ’s grace of the perfect love that casts out fear in purity of heart. The Lord who calls us is free to choose whatever means he deems effective to open our hearts, bodies, and minds to this great gift. An infirmity or injury, a serious diagnosis, that may at first make us feel as if we were struck down by destiny can turn out to be, in fact, a provision made by a kind yet nonetheless cross-shaped providence.

It fills one with reverence to see misfortune received in this way, in a spirit of faith, gently, without bitterness. Each trial has its corresponding grace. We shall find it if we look for it. We shall be fit to look if we learn that for those who love God, all things work together for good. All things. Job’s question, ‘Shall we receive the good at the hand of God, and not receive the bad?’, does not spring from Stoic toughness; it reminds us that the apparently bad, borne in faith, will lead to some ulterior good.

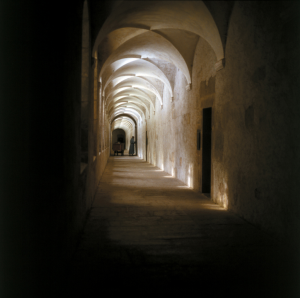

Amma Syncletica’s point about blindness makes me think of a scene towards the end of Into Great Silence, Philip Gröning’s predominantly silent film from 2005 about La Grande Chartreuse. A blind monk lets us sense his initial discomfiture when he saw his sight was failing. Then he says: ‘Now I often thank God for making me blind; he did it for the good of my soul.’ Physical blindness had sharpened his inward view of God’s essential goodness, making him see that all God allows is somehow helpful, preparing us for that solemn moment when all our life’s attempts to say Yes to God’s designs will come together in the final abandonment of death, which the monk insists should be a joyful surrender.

That is how to live — and die.

Still from the film Into Great Silence.