Archive, Articles

Sr Marie-Ange in memoriam

On 17 August this year I attended the funeral of a contemplative nun. She had lived a life of exemplary, contagious dedication in the Loire Valley, in a convent near the town of Le Blanc. The day was glorious, the sun bright and clear but without stinging fierceness, lending a sheen of splendour to the rolling landscape. It was one of those days that make you see how the Psalmist might plausibly affirm that a tree, a flower, a blade of grass can ‘shout for joy’.

There was joy in the assembly, too. This is not to say that the sister was not missed or mourned. She was, for she had been profoundly loved. But I sensed the exultation peculiar (though not unique) to monastic funerals. It springs, I think, from corporate pride in a life well lived to the end; from wonder at the free gift, sealed as definitive by death, of an entire existence, reminding us that love cannot be merited or bought, only given and received; also from the sweet strength that spreads in a crowd ascertaining experientially, each for him or herself yet nonetheless together, that love is stronger than death, that our sense of death’s absurdity does not spring from pathologies of denial, but stands for ultimate truth.

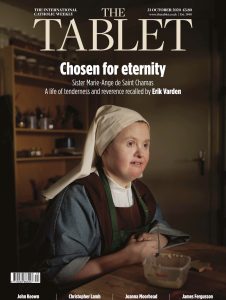

In these ways, the funeral was like many others. It was singular on account of the vocation of the nun we had gathered to bury. Sister Marie-Ange de Saint Chamas had been one of the first Little Sisters, Disciples of the Lamb, an institute founded in 1985 to enable women with Down’s to embrace monastic life. When Marie-Ange was born in 1967, her parents soon discovered she was not like other children. They kept, her sister said in a tribute, ‘this treasure in their heart for some time, the time required to make of it an oblation, to own their perplexity and pain, the time, above all, we needed to learn to love and know her as she was. Little by little, they let us understand that she would be better equipped than we were to maintain the beauty of a child’s heart and would outdo us in her ability to love.’

The prediction of Marie-Ange’s parents was realised. I never knew her alive, yet felt I encountered her that day, such was the wake of tenderness her life’s passage had left. It drew me, a stranger, in, and carried me along; it carries me still. Many were those who spoke of her compassion and courage, her intuitive intelligence, her wisdom and sparkling sense of fun. Striking was the account of her vocation. Marie-Ange’s community is no reservoir for misfits. It is a sanctuary for consecrated women who embrace their calling with lucid dignity. When Marie-Ange heard of the fledgling foundation, she knew it was for her. It corresponded to a deep sense of purpose. She loved to affirm, ‘He has chosen me’ — and would raise a finger to stress the gravity of what was to follow, before adding, ‘for eternity’.

Current discourse on Down’s in the public forum has assumed a weird character. The fact that children carrying the syndrome are no longer, or only exceptionally, born in certain countries is hailed as a triumph of science. What is more, this state of affairs is presented as a function of compassion. Compassion? Implicit (if not pronounced) is the assumption that life with Down’s is unworthy of a human being, that by sparing affected children the chance to see the light of day, one does them a favour. Such is the power of this rhetoric that anyone challenging it risks being dismissed as retrograde or as glorifying suffering, something widely thought, perversely, to be a Christian tendency.

In our political climate it is increasingly taken for granted that some lives are expendable, and probably best spent. This spring, when I happened to have time on my hands, I read a range of newspapers daily. It was intriguing and instructive to see how the Covid crisis was construed differently in different countries. There was consensus about the nomenclature of ‘crisis’ but not about its terms. Whereas in some contexts, coinciding broadly with Europe’s south, the crisis was defined as humanitarian, with radical measures taken to prevent loss of lives, other contexts, say, further to the north, posited the primary crisis as financial, canvassing for remedies to be applied accordingly. Both definitions could claim validity, but surely a qualitative distinction is called for? As far as I can see, it was rarely made.

And I wonder: is it likely we shall get anywhere in the much-vaunted construction of post-Covid society if we do not have shared criteria for evaluation at this level, if we fail to agree on what it means to envisage a world healed and whole?

While the economic order is hyper-connected, we practise social distancing. This does not just concern queues at checkouts. It results, globally, in growing gaps between those who have prospects and those who have none. The latter experience a sense of abandonment that leads variously to grief, fear, and fury.

In such a world, we need people who build bridges, who assume, by office, nature or grace, pontifical ministries. Those who exercise such ministries effectively are more likely to be somehow weak than powerful. I do not think it true that power necessarily corrupts, but it does isolate for the simple reason that it tends to be tied to things that need to be protected. Those who reach out across barbed wire from one camp to another will to be those who have nothing to lose, who are unconcerned even about losing face, prophets of our time who, like Hosea or Ezekiel of old, step into the breach not just by what they say but by what they embody.

At Marie-Ange’s funeral, I was told about another nun of the community who had recently attended a medical appointment. In the waiting room was a woman in distress who had begun to kick and scream, unable to contain whatever anguish possessed her. All withdrew in dismay, with one exception. The nun with Down’s stood up, approached the panicking patient, and told her, Tu es belle, Madame! — ’Madam, how beautiful you are!’ She established instant peace, unselfconsciously enacting a parable of humanity resplendent in its applicability to all.

In a terrific TED talk from 2017, Jonathan Sacks said ‘that a nation is strong when it cares for the weak, that it becomes rich when it cares for the poor, it becomes invulnerable when it cares about the vulnerable.’ This is so not just because it is nice to be nice to the unprivileged. It is so because each of us is, in different ways, at different times, weak, vulnerable, poor. It is a lie to pretend otherwise. Further, it is not the absence of poverty, in whatever form, that repairs the human commonwealth: Christ proclaimed, in words that provoke and challenge, ‘The poor you will always have with you’. Where, then, do we find wholeness? In reverence for others; in genuine encounters; in the collapse of illusions of self-sufficiency.

The former Chief Rabbi’s words chime in with the credal statement of a man uniquely equipped to see where opposite trends might lead, the French geneticist Jérôme Lejeune (1926-94). He evidenced the chromosomal abnormality that causes Down’s, only to realise that his discovery, made in view of healing, would cause large numbers of persons carrying Trisomy 21 to be objects of prenatal non-selection: ‘The worth of a civilisation is measured by the respect it shows its weakest members.’ One might postulate: perhaps not just its worth, but its durability.

At the funeral of Marie-Ange, her siblings told us she had, ‘like a corner stone, a stone our parents did not reject, which solidified our family, directed the path of each one of us inimitably’. The Christian story is the story of a corner stone we, builders of our lives, Church, and society, are free to place where it structurally belongs or to throw into a skip. In a Christian perspective, those mutually exclusive options add up to a hermeneutic by which history can, and must, be read and judged. It is time we applied it to ourselves here and now, asking ourselves without subterfuge what sort of world we are minded to construct, spelling out the stakes.

Have we the courage to do so, we shall find ourselves before a crossroads well known to our ancestors in the faith. It is evoked in the opening words of a precious first-century text, the Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, often known by its Greek name as the Didache: ‘There are two Ways, one of Life and one of Death, and there is a great difference between the two Ways.’ They may run in parallel for a while, but sooner or later they diverge. Each wanderer must then choose where to go.

You can find a documentary film about Sr Marie-Ange’s community here.