Archive, Articles

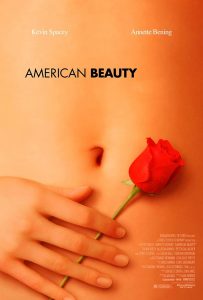

The Demonic Gaze: American Beauty

My purpose this evening is to offer a few personal reflections on Sam Mendes’s film American Beauty, which appeared last year and was hailed throughout America and Western Europe as a major cinematic happening. Based on my thoughts about the film, I shall develop a point which has been much on my mind since I first saw it, essentially to do with the business of seeing, that is of acknowledging and accepting the presence of Another (in an absolute sense) in our field of vision, as an object we are forced to relate to, be it with indifference, with hatred, or with love. What interests me is the problem of alterity, and in order to untangle it, if only a bit, I shall draw on the authority of Evagrius Ponticus, the fourth-century scholar-hermit whose treatise On the Discernment of Passions contains a penetrating analysis of my topic: of seeing as a means of communion with nature, with people, with God.

At this point, you might think, ‘Hang on! How did we get from twentieth-century Hollywood to fourth-century Egypt to God?’ American Beauty was clearly not intended as a theological statement. At least one reviewer has categorically declared that ‘the film’s profundity is only skin-deep’. My introduction, you might think, is an example of the tiresome tendency of theologians to think that they are always the ones who see the true significance of things, invested with a divine right to interfere by which they use inane everyday matters to construct complex layers of meaning which to the lay observer are at best tedious, at worst incomprehensible. I hope to respond to that objection in due course. Suffice it to say, for the moment, that my interpretation of American Beauty does not aspire to objectivity; it does not pretend to unveil a hidden meaning or a secret intention. Every product of human creativity—whether it’s a book, a painting, a film, or whatever—reaches a kind of maturity on entering the public domain; it is freed from the mind of its originator and precariously exposed to the opinions of other minds and sensibilities. What I have to offer is no more, no less than my particular response to a film that intrigues me, and a symbolic, symptomatic analysis based on my particular interests and concerns.

The Plot

What, then, is American Beauty about? According to a review I found on the World Wide Web, representative of many others both in its content and in the quality of its prose, ‘the film denounces the hypocrisy of a society obsessed with an outer appearance of success but is eaten away [sic] by frustration on the inside, thus destroying a certain American Dream. Here, Puritanism, patriotism, empowerment, and corporate America will not be spared’. Social criticism, then, and pretty hefty criticism at that, if in one go it covers (or uncovers) ‘puritanism, patriotism, empowerment, and corporate America’. With those categories in mind, I don’t think it will be a waste of time to go through the plot in some detail, to get our own sense of proportions.

The beginning is stark and abrupt, throwing us into a dark room, where a girl in her teens talks into a camcorder. She talks about her father: about how he has destroyed her life; about her desire for his death. A boy, holding the camera, asks, ‘Do you want me to kill him for you?’. After a short pause the girl replies, ‘Yeah’. The quality of that brief sequence creates the illusion of a home video—rather as in Thomas Vinterberg’s terrifying movie Festen—and we get the sense of sharing a deep and dark secret.

The spell is broken as the perspective changes and credits start rolling across the screen, while the film’s protagonist, Lester Burnham, launches into a voice-over introduction. We learn that Lester is dead, and that his narrative from Beyond will serve to describe the events leading up to his demise. The camera’s bird’s-eye zooms in on Lester’s suburban town, on his street, on his house, while Lester exclaims, as if he were the host in his own talk show, ‘This is my life!’ In five minutes, we have leapt from brutal realism to flamboyant fantasy. We are introduced to Lester’s wife Carolyn, who wears gardening gloves to match her shoes, and to his daughter Jane, an angry-looking teenager who dreams of a breast enhancement. She is the girl we saw at the beginning, wishing her father dead.

Lester is massively frustrated. He has problems at work, he is erotically unfulfilled, and he is tired of being perceived as a ‘gigantic loser’. His wife Carolyn suffers from much the same problems, but deals with them differently. She is a not very successful estate agent, and in a comical but terrible scene we see her furiously cleaning a property she is determined to get off her hands, repeating to herself, ‘I will sell this house today’. Having taken several customers through, none of them interested, she breaks down in loud sobs after closing the blinds, yet immediately regains control by slapping herself and shouting ‘shut up!’. Disappointment and anger are banished through violent self-control, and she walks out composed. At home, the collective frustration of the Burnhams finds multiple outlets behind a respectable, bourgeois façade. Carolyn expresses her discontent through laboured irony. Lester plays the role of a martyr, relentlessly persecuted by his womenfolk when seeking oblivion in front of the television. Jane, finally, says nothing, but radiates loathing.

Next door to the Burnhams, another family drama unravels in the household of Colonel Fitts, a retired army officer, a repressed homosexual, and a domestic terrorist. His wife (who, incidentally, is the only main character to remain nameless, as though dispossessed of graspable individuality) is zombie-like, fragile, and fearful. The Fitts’s son, Ricky, is a loner and ‘freak’. He moves between the resigned absence of his mother and the violent presence of his father with a calm that resembles serenity. Apparently docile, he is in fact, as we progressively discover, the master of the house. Ricky has seen through his father’s iron mask to the chaos underneath, and he skilfully manipulates the Colonel by feeding an illusion of macho mastery, thus clearing the space he needs to carry on his secret life as a freelance drug dealer and camcording mystic. Ricky always has his camera to hand and compulsively photographs instances of ‘Beauty’, his own term for a visual experience that opens up to transcendence by revealing an essence which goes beyond the material form of its object. His photography is a means of establishing communion with the Absolute, as on the ‘amazing’ occasion when he videoed the dead body of a woman tramp. ‘It’s like God looks right at you, and if you’re careful, you can look back. What you see, is Beauty.’

In both households, then, complex dynamics of desire and denial are at work, kept in a fragile equilibrium by somnolent inertia in the case of the Burnhams, by brute force of repression in the case of the Fitts. The dramatic development hinges on a series of disruptive eye-openers which upset the balance. One by one, the main characters go through an awakening that releases hosts of furies, ready to destroy anything and anyone standing in their way. Tragedy ensues when furies bound on different courses collide.

Lester’s awakening is wrought by the unleashing of physical desire through a series of fantasies focused on Jane’s friend Angela. Having seen Angela perform in a cheerleader show, which his fancy turns into a tantalising striptease, he claims to have woken up ‘after twenty years in a coma’. The girl recurs in his dreams, showered with rose petals, as a symbol of lust, youth, and endless possibility. Alert to her father’s infatuation, Jane feels embarrassed. Angela, on the other hand, is delighted. She likes being singled out for attention, since in her view, ‘There is nothing worse than being ordinary’; a fate she will fight by becoming a model—a full-time icon of desire. One day at school, Angela tells two dull-looking girls about going to bed with a fashion photographer, assuring them that, ‘That’s the way things really are’. Her promiscuity stands as proof of her power of seduction.

Lester’s new life is spurred on by the possibility of self-transformation. He leaves his job and blackmails his employer, determined to recapture a feeling of having life ahead. He begins to base his existence not on objective circumstances—on what he can see—but on his fantasy of what circumstances might have been or might become. He becomes reckless: ‘an ordinary guy with nothing to lose’. The new Lester, cool and virile, purchases pot from Ricky Fitts in order to see the world differently, and wants ‘the least possible amount of responsibility’. His attitude exasperates Carolyn, who seeks solace in her professional rival Buddy Kane, with whom she starts an affair. Buddy’s secret of success is simple: ‘Always project an image of success’. To feel powerful, he goes to a shooting ring, a pastime he warmly recommends to Carolyn.

Jane’s awakening to herself also takes the form of an encounter. She first becomes aware of Ricky Fitts one evening when he films her. She feigns fury, but is flattered by his attention. At school the next day, Angela calls Ricky a ‘pervert’, a ‘lunatic’, a ‘nerd’. Jane, however, is fascinated, and delighted to hear Ricky say, ‘I think you’re interesting’. Later, she remarks, ‘He’s, like, so confident; it can’t be real’. A few days later, Angela and Jane find Ricky filming a dead bird, ‘because it’s beautiful’. Jane chooses to walk home with him despite Angela’s horrified objection. On the way, the two of them encounter a funeral cortege. It appears that neither has ever known anyone who has died, although Ricky brings up the incident with the dead tramp.

Taking Jane home, Ricky shows her his father’s guns and Nazi memorabilia while his mother, in a daze at the kitchen table, apologises for the ‘terrible state’ of her oppressively spotless house. He shows Jane a video clip of a white plastic bag played along by the wind among dead leaves against a red brick wall. ‘There was an electricity in the air. You could hear it’. Ricky had felt as though ‘the bag was dancing, like a little kid begging me to play with it’. Visibly moved, he exclaims: ‘There’s this entire Life behind things, this incredibly Benevolent Force’. It tells him, ‘There’s no reason to be afraid’. He films to remember, for sometimes he ‘can’t take in all the Beauty in the world’. His ‘heart gives in’. Jane takes his hand and kisses him. Later she returns the confidence. As she and Ricky stand facing one another by their respective bedroom windows, she exposes her breasts, hitherto an object of shame. Suddenly Colonel Fitts enters, and begins to beat Ricky savagely for tampering with the gun cabinet. The contrast between the two scenes is powerful, with the revelation of intimate vulnerability cut short by blind violence.

A pitch of intensity is building up between Jane’s parents. Hurt by Lester’s detachment, which confirms her sense of worthlessness, Carolyn breaks down one evening, having learnt that, ‘You can’t count on anyone except yourself’. A possible reconciliation, in a seductive moment, is ruined by Carolyn’s shriek as Lester almost spills beer on a $4000 sofa upholstered in Italian silk. Lester, who a minute earlier had asked tenderly, ‘When did you become so joyless?’, regains his distance, crying out: ‘This isn’t life, it’s just stuff!’ The rupture becomes irrevocable when Lester shortly after finds his wife and Buddy in a passionate embrace. It is the peak of his emancipation. Having already relinquished ‘responsibility’ in professional life, he is now liberated from marital obligations. The slick and slimy Buddy, anticipating emotional demands he has no desire to meet, slips out of Carolyn’s life as smoothly as he entered, leaving her to her tears in a motel car park.

The dramatic climax of American Beauty is signalled as we reach, in actual time, the sequence we saw at the beginning. Jane and Ricky are together in Ricky’s room, he with no clothes on. While Jane talks, Ricky films her. She feels uncomfortable, grabs the camera, and films Ricky instead, asking: ‘Don’t you feel naked?’ He responds, ‘I am naked’. Jane talks about Lester, saying that she would have liked to be important to him, as important as Angela, but that she has grown to hate him. Ricky asks, ‘Do you want me to kill him for you?’. ‘Would you?’, says Jane. ‘It would cost you’. After a while, the camera is put away. Now face to face, Jane says, ‘You know I’m not serious, don’t you?’. Ricky replies, ‘Of course’. Yet he is disturbingly remote as he looks at her, and at us. Ricky remarks how lucky he and Jane are to have found one another. Soon he will have no one else.

Colonel Fitts, who thinks that his son’s dealings with Lester are those of a rent boy, not of a drug dealer, attacks Ricky one evening when he comes back from the Burnhams, striking him and screaming, ‘I’d rather you were dead than be a faggot’. Ricky then invests his secret weapon, his hoarded dynamite. Pretending that his father is right, he starts to describe sexual acts he allegedly performs. It renders the Colonel powerless and weak. In supreme control, Ricky scowls at him and says, ‘What a sad old man you are’. He goes downstairs, and tells his mother that he must leave. She replies: ‘Wear a raincoat!’, a mechanical expression of maternal tenderness which permits us to sense an intensity of love and despair which, for lack of expression, has turned in on itself and imploded, creating a lifeless wasteland.

Ricky’s departure into the dark night, during a violent rainstorm, leads up to the key event we have been waiting for: Lester’s death. It is introduced by four brief scenes. First we see Carolyn, sitting in her car and listening to a self-help tape on the way back from shooting practice. The voice on the tape enjoins: ‘Break away from victimhood!’. Driving home, she repeats as a mantra, ‘I will not be a victim! I will not be a victim!’. The second incident is Ricky bursting into Jane’s room, inviting her to run away with him. Jane accepts, despite the protests of Angela, who will not permit her ‘friend’ to be ruined by a ‘freak’. Jane replies that they are both freaks, while Ricky strikes at the real reason for Angela’s concern: ‘Jane is not your friend. She is someone you use to feel good about yourself’. Then he puts in the coup de grâce: ‘You’re ordinary, and you know it’. For the second time in a few moments, he has paralysed an opponent by exposing and touching an aching wound. Left to themselves, Jane asks Ricky whether he is anxious. He replies, ‘I don’t get scared’.

The third scene shows Lester working out in the garage, when Ricky’s father appears outside, asking where Carolyn is. Lester thinks she is out with her lover, but adds that he doesn’t mind: ‘Our marriage is just for show, a commercial for how normal we are, when we’re anything but!’. Colonel Fitts pauses; then, after an interior battle which breaks through decades of denial, comes up to Lester in an attempt to kiss him. Lester wards him off, gently but firmly. The other man steps back, looks at him blankly, then slowly walks back out into the rain.

In the fourth preparatory scene, Lester finds Angela in his living room. She invites him to seduce her, and Lester assures her that she is ‘the most beautiful thing’ he has ever seen. He begins to remove her clothes, but then, unexpectedly, the street-wise sex-bomb is reduced to an anxious child, confessing, ‘This is my first time’. With that remark, Lester’s spell, first cast by Angela, is broken. His eyes are opened. No longer predatory, but paternal, he recognises Angela for what she is: a lonely, insecure girl wanting love. He takes her to the kitchen, where they have a snack and talk about Jane. Lester asks whether she is happy. Learning that she is in love, he says, ‘Good for her!’ Angela asks him how he is. ‘It’s been a long time since anyone asked me that’. Then, ‘I’m great’. Left to himself, Lester sits down with a photograph of himself with Jane and Carolyn, contemplating it with love and murmuring, ‘Man, oh man!’ The next thing we see is a gun put to his head—and his brains blown out. Ricky and Jane run downstairs. Ricky kneels down by his girlfriend’s father’s head, which is covered in blood. He sits there, fixed, his head tilted to one side as though, like on the occasions when he saw the bird carcass or the dead tramp, he is overwhelmed by ‘Beauty’.

An epilogue brings us back to the original narrative, with Lester talking from Beyond. He describes the moment just before his death, which transported him back to childhood. Recapturing his first sense impressions, he was once more a boy lying on his back in the grass, intently seeing the sky, seeing the leaves of autumn trees, seeing his grandmother’s paperlike hands and his cousin Toby’s Firebird, seeing Jane and Carolyn. His account is accompanied by clips of Carolyn storming into the house, finding Lester dead and running up to their bedroom, hiding her gun in the laundry basket, hugging Lester’s clothes, and wailing inconsolably. We see Ricky’s father, covered in Lester’s blood, returning to his house. The film ends with a kind of testament from Lester. ‘I guess I could be pissed off at the way things have turned out, but there is too much Beauty. Some times it is as though I see all the Beauty in the world at once, flowing through me. And I’m filled with gratitude for every moment of my stupid little life’.

The demonic gaze

I admit that after seeing American Beauty for the first time, I felt profoundly unsettled, without really knowing why. One of the film’s characteristics is precisely the studied ambivalence by which nothing really is what it appears to be. The characters are unpredictable, with a protean capacity for change just as we think we have worked them out. Further, the film does not reach a satisfactory conclusion. Most of us, when reading a book or watching a film, like to see the story wrapped up in a coherent ending; whether it is happy or sad does not matter so much, but we want to feel that the narrative has been leading up to something, particularly if it has engaged us emotionally. In American Beauty there are several moments which (at least to me) are moving, even terrifying: Mrs Fitts in the raincoat scene, Carolyn in the carpark, Lester with his photograph. Out of this depth of experience there comes nothing but destruction, desolation, and death, producing a sense of loss which is exacerbated rather than assuaged by Lester’s semi-ironic comments from Beyond. American Beauty made me depressed. When I left the cinema I almost wished I had not seen it.

I managed to forget Lester & Co until just before Christmas last year, when I was busy studying the Philokolia, a collection of Christian ascetic writings from the patristic to the late medieval era which was published in 1782 and which had a phenomenal impact on the Orthodox revival movement known as hesychasm. An important Philokalic text is Evagrius’s treatise On the Discernment of Passions, and here I came across a passage which brought American Beauty back into my mind. In this work, Evagrius expounds the destructive potential of the human imagination, which can corrupt truth through seductive illusions, and then outlines three basic attitudes which define our way of relating to reality and of placing ourselves within it. His hypothesis is that there are three fundamental ways in which human beings see and relate to things: the angelic, the human, and the demonic.

Angelic thought is concerned with the true nature of things and with searching out their spiritual essences. For example, why was gold created and scattered like sand in the lower regions of the earth, to be found only with much toil and effort? And how, when found, is it washed in water and committed to the fire, and then put into the hands of craftsmen who fashion it into the candlesticks of the tabernacle and the censers and the vessels from which, by the grace of our Saviour, the king of Babylon no longer drinks? A man such as Cleopas brings a heart burning with these mysteries. Demonic thought, on the other hand, neither knows nor can know such things. It can only shamelessly suggest the acquisition of physical gold, looking forward to the wealth and glory that will come from this. Finally, human thought neither seeks to acquire gold nor is concerned to know what it symbolises, but brings before the mind simply the image of gold, without passion or greed. The same principle applies to other things as well.

I should like to take a bit of time to reflect on this passage, developing Evagrius’s distinctions of thought in terms of the language of vision. The ‘angelic’ gaze is essentially contemplative. It pauses in wonder before its object in an unselfconscious desire to see it for what it really is, in an attitude open to mystery. The ‘angelic’ intellect recognises the significance of the sacred vessels desecrated at Belshazzar’s feast, regarding them with awe, not for their imposing appearance but for the sublime communion towards which they point and for which they were made. The ‘angelic’ heart, like Cleopas on the way to Emmaus, is so sensitised to the sacramental quality of revelation that it catches fire in God’s incarnate presence. It is the ‘angelic’ sensibility which gives rise to great art, and if, like me, you ever get the chance to live in Paris for a spell, you will find a magnificent example of it in the Musée Marmottan, the city’s largest collection of Monet paintings. On the first floor you find a range of pictures we all know from poster shops: pastel landscapes, fog-wrapped towers, and pretty portraits. The painter here is unquestionably the master, not only of his craft, but of his motive. If you go downstairs, however, to the basement gallery, you are transported to a different universe, among canvases Monet painted at the end of his life. These are chaotic, sometimes violent, and his series of water lilies possess a compelling force that draws you in, like a charmed lake in a German fairy tale. The painter is no longer in control of his subject. He is at its mercy, letting it find its own expression through his art, which thus becomes the sign, the monument, of an encounter.

What Evagrius refers to as the ‘human’ gaze requires no explanation, for we all practise it daily. It is the attitude of hectic indifference which contents itself with the surface of things, with no inclination to penetrate through to deeper layers of meaning. The ‘human’ gaze does not engage with its object. It notices it, acknowledges its presence, and moves on. It exemplifies the mentality of the modern tourist, who does not pause to look at Rubens’ Magi in Kings, say. His concern is simply to verify that the painting is there—that it corresponds to the illustration in his guide book—and to tick is as ‘done’ before rushing out to find the Mathematical Bridge. A splendid example of someone whose outlook is confined to the ‘human’ is Paul Bernheim in Joseph Roth’s novel Left and Right; a character who is constitutionally superficial, and so caught up in the drama of his own existence that the rest of the universe becomes an incidental stage set, as when he turns to the study of art for the purpose of improving his conversation:

Soon he could see no man, no street, no corner of a field without citing a famous master or a well-known painting. Already as a young man, he outshone every art historian of renown in his inability to perceive anything at all with immediacy and to describe it simply.

The ‘human’ mind is fundamentally egocentric in so far as it does not attribute real importance to anything exterior to itself. It is the sun in a universe of extinguished stars.

The ‘demonic’ gaze, finally, is more ambiguous. Like Lucifer and the fallen angels, it has looked on the face of God and seen the glory of heaven. Instead of being lost in wonder, however, it sets out to grasp and possess. It perceives the Other as food to be consumed for its own nourishment, like Dracula seducing his victims to consume their life force. In Evagrius’s terms, this attitude is blasphemous. Endowed with an angelic perspicacity that senses the transcendent mystery of otherness, the ‘demonic’ man or woman displays no reverence but, on the contrary, delights in challenging the power of God. Belshazzar (to return to Evagrius’s example) was not, by feasting from the vessels of the temple, merely proving his royal licence to gratify an impious desire; he was telling the God of the Jews that he had met his match. The ‘demonic’ gaze usurps a divine perspective in presuming to appropriate for its own good pleasure things and beings created to be themselves. Seeking possession rather than communion, the ‘demonic’ grabber upsets a divinely instituted balance. Like the king of Babylon, he will sooner or later see the writing on the wall.

When reading Evagrius, I immediately thought of Ricky Fitts. The first thing we see of him are his eyes, concentrated and intense, and throughout the film he is presented as someone who sees through surfaces to what lies underneath, someone who, indeed, trains others in the art of seeing: Lester, by providing drugs which reinforce a new-found outlook of desire; Jane, by training her to perceive ‘Beauty’ where she had not expected to find it; his own father, by exploding a barricade of delusion. Of all the characters in the film, Ricky is the one most difficult to pin down. Personally, I first regarded him as a kind of hero, endowed with the vocation to awaken others from their torpor. The early scene with the ‘beautiful’ dead bird seems to reveal the sensibility of a poet; an ironic and perverse poet, perhaps, but a poet all the same, like Baudelaire writing polished verse on a putrid carcass in the Fleurs du mal. Later, when he expounds the revelation of the white plastic bag, poetry becomes a kind of mysticism, with a supernatural, personified object: an ‘incredibly benevolent Force’ which is Life and Beauty, and which tells human beings not to be afraid. Ricky, I thought, is someone who has discovered that he has a soul, and who seeks to bring others too out of two-dimensionality. I thought of him as a New Age apostle of alterity, whose gospel is the revelation that the world is a place of encounter, inviting a communion of being that banishes loneliness. Perhaps I wasn’t altogether wrong—but I was only partially right.

For Ricky is not someone to pause reverently in wonder. He records and appropriates, and only contemplates Beauty once he has it on tape, that is, once he has materialised and captured it. With people, likewise, he collects and stores insights which will be deftly deployed at crucial moments as means by which to impose his own dominion. Ricky’s detached superiority has great force of seduction. Both Jane and Lester are entranced by his confident fearlessness, manifest with symbolic force in the film’s first scene, when Ricky, naked and, therefore, apparently vulnerable, undertakes to kill Jane’s father. The scene is almost an inversion of Adam’s post-lapsarian embarrassment in the Garden, for Ricky knows himself to be naked but is emphatically not afraid, not ashamed. He does not run away and hide upon seeing himself uncovered; instead he assumes the divine prerogative of acting as an arbiter of life and death. He really does seem to have ‘become like God’—and his attitude stands out all the more since almost every other character in the film frantically follows the opposite course, heaping up fig leaves for camouflage.

Lester, first of all, seeks to shatter his status as a loser by inventing an identity of strength and seduction; Carolyn clambers up from an abyss of loneliness projecting ‘an image of success’; Angela instructs others in the way things ‘really are’ based on hypothetical criteria. For Colonel Fitts, finally, the image is all. When it is shattered he is left with nothing but a painful void, symbolised—in another image with biblical overtones—by the storm into which he returns after revealing himself to Lester, swallowed up by waters of chaos over which no life-giving, form-imposing Spirit is brooding. Naked and exposed, he has recourse to one response only: destruction. The experience of having been seen for what he is has been so terrifying that the observer must be eliminated. In all four cases, assumed identities operate as stratagems to conceal fundamental human needs for tenderness, love, and esteem. All four want to be wanted, but for fear of exposing need they construct modes of self-expression which are aggressive, mendaciously self-assured, and ultimately isolating. We could say, in Evagrius’s terms, that they are striving to appropriate the demonic gaze, substituting the dynamic of desire and possession for that of love and communion. The chief characters of American Beauty are all trying desperately hard to become needless power-wielders. But they are not the masters of that game; they are at its mercy. Pursuing the metaphor, we could say that they are possessed by the demon-dominator, whose property it is to turn victims into its own substance.

In Lester’s case, the Evagrian terminology is particularly apt, for we witness his progression from a ‘humanly’ indifferent through a ‘demonically’ grasping to an ‘angelic’ sensibility. What happens in his last, decisive encounter with Angela is that he recovers the gift of sight. Waking up from a fantasy—from a trip—he recognises as a mysterious, vulnerable, ineffable other the girl whom so far he had perceived only as an object of his own passion. Shells fall from his eyes, and he sees the truth about himself and others with a new and piercing clarity. Not for very long, however. Lester’s awakening to Reality seems to condemn him to leave this world by force of some brutal determinism, and he is immediately dispatched to another realm where seeing is all and where Beauty ‘flows through’ him. Lester arrives in a made-to-measure dreamland paradise, while his dead body is apparently transfigured as the pool of blood in which it lies fills with rose petals, the symbol of desire. Lester has been swallowed up by Beauty, and cheerfully rides off on a cloud into a sunset of celestial impassibility while, on earth, his wife cries her heart out in a cupboard, his daughter keeps vigil by his corpse in bereft horror, and Ricky Fitts, the fearless and needless, contemplates the flow of his blood with morbid fascination. The end of the film, like its beginning, posits a stark juxtaposition of harsh realism and elusive fancy; of a jolly reverie played out against a background from which, like pistol shots, we are hit by sudden eruptions of intense, unbearable pain.

American Beauty does not, clearly, belong in the league of Tarkovsky or Bergman or Kieszlowsky, but the film is nevertheless a powerful investigation into patterns of human relationships which goes far beyond mere social criticism and which, by its use of symbols and signs, opens up to a theological assessment in which key terms like ‘fall’, ‘redemption’, and ‘communion’ are not out of place. Sam Mendes does not, I think, pursue a coherent line in this respect; indeed, it is, once again, the film’s ambiguity which lends force to its enquiry, to the questions it puts. Is ‘Beauty truth, truth beauty’, in a pseudo-Keatsian kind of way? Is Beauty really inseparable from death? Is the world a ‘sea of symbols’ pointing towards God, to borrow a phrase from Ephrem the Syrian? If so, who—what—is that God? Are we, as human beings, condemned to an attitude either of ‘human’ detachment or ‘demonic’ greed in a universe that has no place for ‘angelic’ communion? I would venture to claim that these are the concerns which made of American Beauty a cult film, not its attacks on ‘puritanism, patriotism, empowerment, and corporate America’. If I am right, the film deserves to be taken seriously—as a cultural, or counter-cultural, statement—even by Cambridge divines, for it is surely part of our vocation and utility to provide, as far as possible, intelligible answers to questions touching our discipline, even when they are obscurely and indirectly put? American Beauty provides paradigmatic evocations of human beings frustratedly seeking the Other in each other, in the natural universe, and in God, wanting to transcend themselves in love, but repeatedly falling back on a painful, pitiless solitude in which ‘you can rely on no one except yourself’. Faced with such existential anguish, theologians have, it seems to me, a responsibility to engage anew with essentials, telling again the story a God who does ‘look right at us’ and who does invite us to look back, not with a ‘demonic’ gaze set to dominate and possess, but in an ‘angelic’ serenity which freely admits the freedom of the Other, whose Beauty is boundless communion.

Addressed to the Theological Society of St John’s College, Cambridge