Archive, Readings

Desert Fathers 25

You can find this episode in video format here – a dedicated page – and pick it up in audio wherever you listen to podcasts. On YouTube, the full range of episodes can be found here.

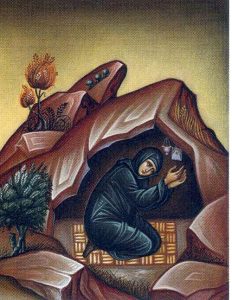

It was said about Amma Sarra that for thirteen years she remained strongly embattled by the demon of lust and that she never prayed for the combat to depart from her; she said simply, ‘My God, strengthen me!’ Further it was said about her that the spirit of lust attached itself to her more vehemently still, spreading out before her the world’s vanities. She, though, never wavered in the fear of God or in ascesis. One day she went up to her room to pray. The spirit of lust appeared to her bodily and said: ‘Sarra, you have vanquished me.’ But she said to it: ‘Not I have vanquished you; Christ my Lord has.’

Some of the Desert Fathers were Mothers. The ascetic vocation was mixed from the start. Antony entrusted his sister to a group of virgins: some sort of religious life was already in existence. The women we encounter in the desert are the men’s equals, sometimes their superiors. Faced with the example of Mary of Egypt, the monk Zosima exclaimed: ‘Glory to you, Christ our God, who have shown me by this servant of yours how far I am distant from perfection.’

Sometimes the women set the men right, and very effectively. We read of a monk who, on his way somewhere, ran into a company of nuns. He stepped aside from the road in order not to set eyes on them, fearful of being sensually snared. This earned him a quip from the Mother Superior. She said: ‘You there, had you been a perfect monk, you would not have noticed that we are women!’ Ha! She did not mean that she and her sisters had dissembled, or transcended, their feminine appearance; she referred to the monk’s way of seeing them. A perfect monk will look for in people he meets an image of God, a messenger from Christ, and see them in the light of the kingdom where there is ‘no longer Jew or Greek, slave or free, male and female’. If his heart is pure, and he is free from passion, he will not need to run away from anyone: he will greet all gently in Christ’s name, reverence them, ask a blessing, then pass on untroubled.

The stories told about Amma Sarra tell us how a pure heart is forged. They speak of combat, of being embattled, attacked. Peace, we have remarked, does not rise into consciousness as mystic mist. It must be conquered. Even as we these days run, or go to the gym, to get our bodies into shape, our inner life requires exercise. Virtue is not tested where temptation is absent. Temptation has its part to play in Christian maturing. Amma Sarra, an example of fortitude, reminds us of this.

In recent years there has been debate about the last article of the Our Father. In Latin, the Church’s mother tongue, the phrase goes: ne nos inducas in tentationem. For ages we have prayed in our vernaculars: ‘Lead us not into temptation’. Then, recently, folks got scruples. God is our loving Father, is he not? What father knowingly leads his kids into temptation? The thought seemed shocking. Liturgists set about adapting the prayer. So, in Italy and France, for instance, one no longer prays, ‘Lead us not into temptation’, but rather, ‘Let us not enter temptation’ or ‘Let us not get stuck in temptation’. The Greek text, though, says clearly: ‘Lead us not’. What it expresses is healthy diffidence. Temptation can take us to our limits. That is dangerous terrain. We ask, ‘Lead us not’, aware of our unreliability and frailty. At the same time we know that if God nonetheless does lead us, he does it for a reason; because he has a plan that will serve our salvation and the thriving of his holy Church. Temptation is devilish only in so far as we suspect the experience has no sense and is purely destructive. That supposition comes itself, though, from the evil one from whom, at the end of the prayer, we ask to delivered once for all.

Must we really prevail on the eternal God to conduct a little aggiornamento to fall into line with current pastoral guidelines? Surrounded by secular notions that life ought to be straightforward (and that if it isn’t, someone is at fault and should be sued), we, now, take a dim view of temptations. They seem to us unfair, for they disturb our calm. But God’s concern is not to keep us comfortably undisturbed. His concern is that we should know the truth, which alone sets us free. A life in untruth is not happy. The Bible tells us repeatedly that God uses temptation to prepare men and women for a task and to free them from illusions. Temptations can clarify, even purify. In temptation we realise where our vulnerability is. We learn to cry for help and to let ourselves be strengthened and healed. A temptation is not necessarily a curse. It can be a summons to battle, an exodus at last from noxious dependencies or from self-centredness. If we pray, ‘Let us not enter into temptation’, it might be tantamount to saying: ‘Let us not grow up; we prefer to stay children.’ That was not an option for the valiant Amma Sarra. She abode within temptation as within a crucible. What emerged, by grace, was gold. The devil was not pleased. Having failed to trip her up by sensuality, the enemy tried another track, tickling Sarra’s vanity. We can imagine her snorting as she replied: ‘Not I have vanquished you; Christ my Lord has.’ This is how a Christian warrior, a true Christ-bearer speaks.