Archive, Readings

Desert Fathers 33

You can find this episode in video format here – a dedicated page – and pick it up in audio wherever you listen to podcasts. On YouTube, the full range of episodes can be found here.

[Abba Isaiah said:] Of all battles, xeniteia is the foremost, above all when pursued in solitude. He who flees to another place leaves all that is his behind. What he takes along is perfect faith, hope, and a heart that is steadfast against manifestations of self-will. For [the demons] shut you up in spirals by all sorts of means. They inspire in you fear of temptations, of harsh poverty and illnesses. They submit to you thoughts like this one: ‘If you fall into such things, what will you do, having no one who knows you and is prepared to look after you?’ God’s goodness, meanwhile, puts you to the test in order that your zeal and love of God may be revealed.

Even as it is risky and irresponsible to cite verses of Scripture out of context as if they were absolute, self-sufficient utterances, we must beware of reading the sayings of the Fathers isolatedly. We may of course have recourse to anthologies of the sayings, or put together our own, which is rather what I am doing in this series. What we must guard against is the attempt to simplify a many-faceted tradition.

The very idea of a ‘systematic collection’ of teachings could lead us to assume that a single coherent line is being followed, with all component parts aligned to it. But no; there is immense variety in the Fathers’ approaches, for human experience is various, as are human needs, human vocations. The sayings, we must never forget, are almost always situational. They respond to specific questions arisen in specific circumstances. A counsel appropriate for one monk in a particular temptation might be disastrous for another monk going through something quite different.

The Fathers sought to be ‘all things to all people’. The foundation for their discernment was undisputed: Christ’s Gospel in all its radicality, with not an iota laid aside for convenience. They knew, though, that Christ, supremely free, ‘plays in ten thousand places,/Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his’; and so that the task of a spiritual father or mother is not to impose a single one-size-fits-all model of putative perfection, but to assist the workings of a personal providence. As a result we find instances, in the collection, of apparent contradiction as, now and again, advice is given that seems to fly in the face of principles previously laid down as axiomatic.

Think of Abba Moses’s aphorism, which we have studied: ‘Go, sit in your cell, and your cell will teach you everything.’ The overarching counsel is that of staying put, of not roaming, of growing where one has been planted. It seems like an incontrovertible condition for monastic living.

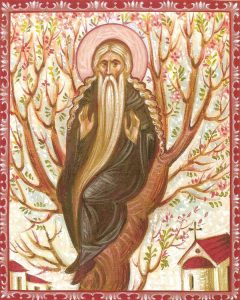

Yet here we have Abba Isaiah praising xeniteia, a practice by which one relinquishes the claim to have any cell at all. A xenos in Greek is a foreigner. Xenophobia is fear of people who are not locals. Xeniteia is at heart a neutral term indicating the state of living abroad, be it as a trafficked worker or as a wealthy retiree in a comfortable flat on the Costa del Sol. In Christian tradition, though, the word acquired special significance. For the early followers of Christ, xeniteia was a way of imitating faithfully the Son of Man who, unlike the foxes in their holes, the birds of the air in their nests, ‘has nowhere to lay his head’. There was a time when monks and nuns took this imitation to picturesque extremes. Some became itinerant, having no fixed dwelling, mortifying the natural human instinct to call a place home, recalling Paul’s words, ‘Our homeland is in heaven’. A few, known as dendrites, refused even temporary earthly repose, and slept in trees.

To understand Isaiah rightly, we must pay heed to his criteria for xeniteia. He is not speaking of an urge to set out because the place where we happen to be bores or frustrates us, because we do not like the food, or the singing, or our fellows. He would have spurned such an idea and held fast to the principle of Abba Moses. We are not to flee from battles that reveal our weak spots. He envisages rather situations in which a particular place has become too comfortable, in which the monastery, be it austere, has come to constitute a cozy nest made up of material security, familiarity, and predictability, features that may cause us to forget reliance on providence.

The true practitioner of xeniteia is not an adventurer, but a woman or man resolved to put their faith in nothing but God alone, cutting through spirals of paralysing self-will (which the devil knows how to exploit so expertly), wishing only to grow in zeal and love. We see this sound yearning for the unknown typified throughout Church history as noble Christians surrender all into Christ’s hands.

We see it in the Celtic saints who set our from well-known shores in boats unequipped with either rudder or sail to let God lead them as he pleased; and we see it in Thérèse of Lisieux when she dreamt of being moved to a Carmel in some far-off land where she would know no one, that she might be anchored more firmly in Jesus alone. It is up to the Lord whether such a desire is realised; our task is not to get so settled in our present setting, our everyday life made up of well-loved, reassuring presences and things, that we turn deaf to the Bridegroom’s call to go out and meet him. We know neither the day nor the hour; but should always serenely expect that it might be right now.