Life Illumined

About St Olav

This year’s homily for the feast of St Olav has attracted attention both in national broadcasting and in a newspaper. It is good to reflect on these matters.

Here is my contribution to a conversation with NRK (the national broadcasting service):

– A pretty simplified representation of the Norwegian early Middle Ages has become popular, says Varden referring to films and TV series about the period. It is important, then, for both cultural and religious reasons to relate to the past responsibly and objectively. Varden says it matters to have a right notion of what a saint is and is not, and that this was what his homily was about. If the guides in Nidarosdomen paint an insufficiently nuanced picture of the story of Olav, Varden would see it as a matter of concern. Varden says the version he referred to in the homily has been referred to him by two or three visitors. – That may have been untypical, he says. I don’t know, but one can hope so. If the remarks I made during the high mass contribute to in-depth reflection on this subject, I rejoice, the bishop says.

And here is a comment made to the paper Vårt Land:

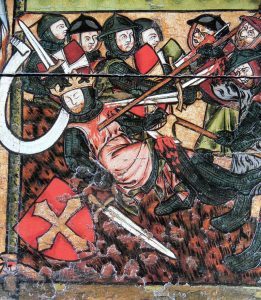

Anyone who takes the trouble to actually read what I said at Olsok, will see that it was not about running others down. When I referred to a one-sided reading of history, I said it regarded us, Norwegians of today, as a whole. We must be vigilant. I explicitly pointed out that Olav, the historical character, is many-faced and unidealisable. My point was to emphasise the conversion that is discernible notwithstanding all the human mess, in order to take that as a constructive challenge for us, now: the homily was a call to conversion, a call that concerns me above all. What the Church for nearly a thousand years has recognised in Olav is an example of what God’s mercy can achieve quite undeservedly in a human being who is riven by conflicts, yet is receptive. If I allowed myself to be a little polemical it was to confront the claim that Olav’s canonisation should have been a clerical project driven by church-political calculation. The cult of Olav spread as a popular movement accompanied by people’s concrete experience of the saint’s intercession and protection. That is why I appealed to the discernment of our forebears a millennium ago. They were not more inclined to suffer fools gladly than we are today. The development of popular devotion to St Olav shows the impact Christianity had on medieval Norway in forming a perspective premised on the hope that man’s, and so society’s, essence may be transformed by grace. Anyone who assumes a priori that references to supernatural reality are a nonsense and that the notion ‘holiness’ does not correspond to any kind of objective reality will consider this development meaningless; and will thus have little chance of understanding how people thought, what they feared and what they rejoiced in, how they made vital decisions in the centuries of faith. The legends of Olav, and with time the liturgy composed in his honour, give poetic voice to an inner familiarity with the saint that people recognised. These sources, too, must be approached responsibly and with empathy. That requires a different kind of hermeneutic than the one required for engagement with linear historiography. We have largely lost the habit of reading images these days; perhaps we are not all that good at reading poetry either.