Words on the Word

Easter Day 2025

Even Klassekampen [a daily paper that began life under the aegis of the Marxist Leninist movement] takes it for granted that its readership will, in their inner ear, hear the resonance of our country’s signature Easter hymn Easter Morning Cancels Grief. That appeared from yesterday’s newsletter.

Grundtvik wrote this hymn in 1843, it was set to a melody by Lindeman. Both text and tune are festive. The music is defined by an implacably major key and proceeds by way of chromatically rising chords: ‘Guilt is redeemed, darkness weeps, to us light and life are given in sweet sunshine.’

Grundtvik wrote this hymn in 1843, it was set to a melody by Lindeman. Both text and tune are festive. The music is defined by an implacably major key and proceeds by way of chromatically rising chords: ‘Guilt is redeemed, darkness weeps, to us light and life are given in sweet sunshine.’

We do believe this! It is true! But how might we celebrate Easter if our heart is tuned in a minor tonality; if our life does not let itself be ordered by means of bombastic end rhymes; if when we look around, at ourselves and the world, we are fearful?

One reason why otherwise sensible people may distance themselves from Christianity, I sometimes think, is the impression they have that Christians who believe in Easter must somehow inhabit a make-believe world, obliged to pretend that the sun is always shining and always to whistle cheerful tunes. That we don’t should be obvious. Furthermore, it appears from the Gospel, which speaks of perplexity in the face of Christ’s resurrection, of uncoordinated reactions, hesitant response.

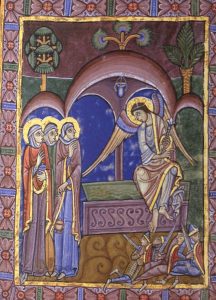

People mill about. Mary Magdalene hastens from the grave to Peter and John; the two then run to where she set out from, apparently racing; or did Peter let John get there first, uncertain of what he might say, should Jesus be found living, he who only on Thursday night denied his friend?

Be that as it may. Finally the disciples, the beloved and the not-yet-rocklike, arrive and ascertain: He is not here. His shroud is, so is the napkin that covered his face, neatly folded the way we might fold our pyjamas before taking our morning shower.

Christ’s victory over death is apparent, first, as absence. Here one is, in the province of death, within the tomb, surrounded by death’s accoutrements; but there is no dead body.

John ‘saw’, we are told; then he ‘believed’. May he have been mindful of words heard just three days before, ‘This is my body, given for you’? A body given in this way, to give life, must surely be alive? Faith rises in John like a slow Norwegian dawn.

To believe in the resurrection; to believe that by baptism we have been incorporated into Jesus’s death-defying body, that our life is ‘hidden with Christ in God’, that guilty humanity has been reconciled — none of this means that everything automatically falls into place. Our world is and remains a vale of tears. Even though the victory of grace has been won once for all, it must constantly be kneaded afresh into concrete lives, surrendered to our freedom. The kingdom of God must be lived into unfolding history. It depends on you and me.

A few days after the encounter at the empty tomb, we find Peter and John again, this time in the presence of the Risen One, by the Sea of Tiberias. Jesus asks Peter: ‘Do you love me? Will you live as I have taught you?’ (John 21.15-19, 14.21).

He poses the same questions to us. Our answer in principle is clear, but must become embodied, like anything to do with Christianity.

The New Testament likens Easter faith, life in Christ, to yeast. The dough must be leavened. That is our life’s task. The yeast culture lives, count on that. Only do not put it in the freezer. Provide it with the conditions it needs. Then it will slowly but surely suffuse your life’s ingredients and fill them with nurturing strength.

Life’s own Champion, slain, yet lives to reign. Live by that certainty and you will ascertain it exultantly, in crescendo. It will turn into your uniquely new song (Ps 96.1).

The Lord is risen, truly risen! Alleluia. Amen.