Words on the Word

2. Sunday of Christmas

Sirach 24.1-12: In the beloved city he has given me rest.

Ephesians 1.3-18: May he fill the eyes of your heart with light.

John 1.1-18: His own received him not.

Today, on the second Sunday of Christmas, we hear again the Prologue of St John as a resonance of Christmas Day, albeit orchestrated differently. The liturgy educates us in this way, carefully weaving together known motifs in expanding harmonies. We hear a certain theme in one context. It speaks to us clearly, carrying an obvious message. Then we hear it again, within different tonalities, and it seems quite different, challenging and questioning.

Our focus is on the Word made flesh. We are reminded of who he is, the Child in the manger: ‘Through him all things came to be, not one thing had its being but through him.’ The Newborn One is the origin of all things; the Infant surrendered to primary needs is also the Power that sustains the universe. We need to keep these paradoxes present in our mind with resolute perseverance. This is where we find the core of Christianity. The human, touching aspects of Christmas — its aesthetics, which charm even sworn atheists — enable emotional access to the mystery of the incarnation. Such access is important, but not sufficient. Faith cannot be reduced to feelings. Faith presupposes enlightened reason.

If we confess, ‘God was made man’, we need to have a notion of who God is. Only when we start to realise what it really means to believe in one all-powerful Creator of heaven and earth, Giver of life, do we see how revolutionary the Christian faith is. For if I truly belive that this boundless God freely let himself be enclosed in Mary’s womb to became a man like us, that faith impacts on every aspect of human living. Even my self-understanding is then conditioned by my faith in Christ, for he shows himself at once the origin and end of my existence, and for existence as such. Faith cannot then just be a Sunday matter, a spiritual boost for the day of rest; it must saturate my life entirely. We wish, do we not, to be integral women and men? It is evident, then, that our lives must be ordered according to an integrating principle.

Christ is that principle. By his commandments and example he teaches us how to live it out; by his sacraments he gives us grace and strength to be formed in his image. Do I say Yes! to his call? Do I let the Word become flesh and grow organically in my own life, or do I keep the Word at a distance, rather like a radio left on in the kitchen while I get on with my business in other parts of the house, but which reassures me when, now and again, I pop back in to put the kettle on? This is the question the Church asks us today, now that Christmas is ripe, so to speak. ‘He came to his own’, writes John, ‘but his own received him not.’ That tragedy is still ongoing.

It is by setting the Prologue of John side by side with a wonderful passage from St Paul that the liturgy bids us examine ourselves in this way. The Letter to the Ephesians gives us an account of what a Christian life looks like. Paul was at least as metaphysically minded as John, but had, too, a consummate pastoral gift. He helps us to integrate ourselves into a perspective on eternity, and thereby renders the very term ‘eternity’ less distant. For eternal life, says Paul, is not a reality subsisting outside time, or that start the moment time ends. We can know eternity now in so far as we live our lives in Christ, filled with his love, moved by the zeal that shaped his being, the zeal to pour himself out utterly, to become a measure wholly filled with the Father’s grace and truth, an embodied act of praise and a bearer of comfort to the world.

To live on these terms entails a degree of mortification, though that word must be qualified. What must die is not our authentic self, what we are in truth; on the contrary, this essential kernel is called to unfold fruitfully. It is the illusion about ourselves that must perish. This comes about when we let the hand of God form us here and now through the message of the Gospel and the teaching of the Church, through the dispositions of providence and the needs we encounter in ordinary life — opportunities to make choices consonant with the creed we profess.

Paul’s text is redolent with an enthusiasm we must try to appropriate. ‘Just think!’, he says: ‘in Christ God has chosen us before the foundation of the world to be holy and spotless before him.’ We are called to holiness, life in plenitude. Will we then be content with a kind of half-life enclosed in our complexes, griefs, wounds, and frustrated desires rather than spent in love, open to receive God’s gift, ‘grace upon grace’, to pass it on to others? We are enabled to be spotless. No stain on our conscience is so stubborn that it resists the Vanish mixture of God’s power, dispensed through Confession and the Eucharist. Do I embrace this grace in order to live in accordance with what God makes possible for me? Or do I choose instead, by laziness and ingrown habit, to keep pouring chocolate sauce over my baptismal garment?

The choices we make impact majorly on our own lives. But that is not all. Each of us is responsible for the whole. The Church is a body. When a single member consents to grace, the whole organism is graced. Our negative responses are likewise consequential.

At the beginning of this new calendar year, we are conscious of the precarious state the world is in. I think of a letter I re-read the other day, written by Dom Porion, the Carthusian, to Jacques Maritain, in 1939. ‘The one thing that matters now’, wrote the monk, ‘is the awakening of Christian conscience, which to all intents and purposes is lame before certain problems.’ The awakening depends on all of us. The eyes of our heart must be filled with light, as St Paul says. The light has been given us. The darkness cannot overcome it.

May we witness to it it faithfully, credibly. Amen.

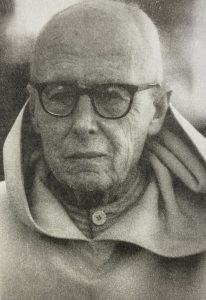

Dom Jean-Baptiste Porion as an old man. In the cited letter he wrote to Maritain to thank the philosopher for his book Twilight of Civilisation: Crépuscule de la Civilisation m’a fait un très grand plaisir: puissent de telles pages ouvrir les yeux à tant de chrétiens si peu soucieux de sincérité. La seule chose qui importe maintenant, c’est le réveil de la conscience chrétienne, – si exactement nulle en pratique devant certains problèmes.