Words on the Word

2. Sunday of Lent C

Gen 15.5-18: Terror seized him, great darkness.

Phil 3.17-4.1: Our homeland is in heaven.

Luke 9.28-36: The aspect of his face was changed.

In the Gospel narrative, the transfiguration on the mountain represents an exception. We otherwise see Jesus from conception to death in recognisable, human shape. True, he did live in evident intimacy with the Father: to see him at prayer was deeply impressive (Mk 1.35). He said wonderful things: people exclaimed when they heard him, ‘No man has ever talked like this’ (Jn 7.46). He wrought great works: wherever he was, gawkers assembled in such numbers that there was no space to move (Mk 2.2.). Still, he was a man like others, a man at home in this world. The very fact that he was ordinary became for some a stumbling block: ‘Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary and brother of James and Joses and Judas and Simon, and are not his sisters here with us?’ (Mk 6.3).

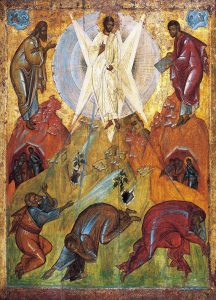

Theologically, meanwhile, the transfiguration represents a norm. On Tabor Peter and the Sons of Zebedee glimpse the mystery of Jesus’s divinity. They intuit who he, their Master and Friend, is. Thereby they realise how little they in fact know him. The light that not only surrounds him but suffuses him, right into his clothes, fills them with awe. At once they are ‘heavy with sleep’, writes St Luke. Mark tells us they were ‘terrified’ (Mk 9.6). One response may well be the expression of the other, as we ascertain later in the Gospel, on another mount, while Christ prays in Gethsemane.

The message of God’s exaltation and absolute otherness was part of the revelation to Abram from the beginning. We must remember that Abraham, our father, was the product of an age that recognised divine realities but conceived of them in material form. Think, for example, of the story of Jacob’s departure from Haran after years of toil in the service of his unsympathetic uncle, Laban. On the day when Jacob and his family set out towards Canaan, Laban was busy, out shearing his sheep. Rachel, his daughter, caught the opportunity to pinch his ‘household gods’, a group of figurines so modest in size that they could easily be hidden in a perfectly ordinary camel-saddle (Gen 31.19, 34). What we face here is an image of archaic religiosity that ties notions of transcendence to concrete things. Laban’s household gods are conceptually related to the figure of Thor that St Olav struck to smithereens down at Hundorp; or, for that matter, to the figures Madama Butterfly reverently carried in her little suitcase when she made her way up the hill, bearing her cultural heritage, to marry Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton, that scoundrel.

The message of God’s exaltation and absolute otherness was part of the revelation to Abram from the beginning. We must remember that Abraham, our father, was the product of an age that recognised divine realities but conceived of them in material form. Think, for example, of the story of Jacob’s departure from Haran after years of toil in the service of his unsympathetic uncle, Laban. On the day when Jacob and his family set out towards Canaan, Laban was busy, out shearing his sheep. Rachel, his daughter, caught the opportunity to pinch his ‘household gods’, a group of figurines so modest in size that they could easily be hidden in a perfectly ordinary camel-saddle (Gen 31.19, 34). What we face here is an image of archaic religiosity that ties notions of transcendence to concrete things. Laban’s household gods are conceptually related to the figure of Thor that St Olav struck to smithereens down at Hundorp; or, for that matter, to the figures Madama Butterfly reverently carried in her little suitcase when she made her way up the hill, bearing her cultural heritage, to marry Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton, that scoundrel.

What a contrast between such notions of easily packaged, portable divinity and the story of Abram’s encounter with the one, living, uncontrollable God!

When we meet Abram in today’s reading, he has already followed God’s call for some years. He has, on account of famine, spent time as a refugee in Egypt; he has been blessed by Melchizedek and interceded for Sodom. But an heir has not yet been given him. The accomplishment of God’s original promise, ‘I will make you into a great nation’ (Gen 12.2), seems remote.

But then the Lord comes to confirm his words: Abram’s descendants will be as numerous as heaven’s stars. By way of a pledge, God appears. The revelation happens inwardly first, in Abram’s soul. Note that the presence of God calls forth, in his case too, the shared effect of sleep and terror, great inner darkness. Then the Lord shows himself recognisably as flaming, devouring light. Abraham ‘feared God’, the Bible tells us (Gen 22.12), not in the sense that he wandered about being anxious, but in the sense that he recognised the abyss separating him, a creature of dust, from God’s uncreated, ineffably glorious being. Having caught sight of God, Abram learnt what adoration means.

Something similar happens on Tabor. In the human nature of Jesus God draws near to us and becomes accessible. ‘Let the little children come to me!’, Jesus cries out (Mk 10.14), and they do come, quite without complexes. Let us not, though, reduce Our Lord to a kindergarten uncle. He remains, even in his self-outpouring, ‘God from God, Light from Light’. When he encounters us at our level, it is not in order that we should remain there, simply affirmed in our present state; it is to pull us upward to himself, that we may establish a new life where he is. Our homeland is in heaven; here on earth, on this earth so dear to us, we are as if in a departure terminal. No one has a permanent abode in such a place, even if we’re fortunate enough to have access to the Senators’ Lounge.

By being transfigured to his disciples, Jesus gives them a new perspective on what they have so far experienced and on what lies ahead: at this point Calvary is clearly visible on the horizon. They realise that the Gospel is not just a project of self-improvement; it is the beginning of a new heaven and a new earth in which God will be all in all. The fact that Moses and Elijah, the Law and the Prophets in person, so to speak, naturally appear within the radius of Jesus’s glory proves that death is not a matter of final consequence — death, in fact, is rather overrated.

To walk in God’s light is to walk beyond limitations of time and space, embraced by a greater reality, entrusted a task that reaches to the ends of a universe that for us appears infinite. ‘This is my Son, the Chosen One: Listen to him’, says the voice issuing from the cloud that, just as during Israel’s exodus, testifies to the Father’s presence.

Yes, that is exactly what we will do. For he alone lets us see reality in a true perspective. His word is truth. If we follow it truly, we shall not stumble, here or in eternity. Amen.