Words on the Word

3. Sunday A

Isa 9:1b-4: The yoke, the bar, the rod of his oppressor, these you break.

1 Cor 1:10-13, 17: ‘I am for Paul, I am for Apollos.’

Mt 12-23: Μετανοεῖτε.

The First Letter to the Corinthians was written less than twenty years after the Lord’s holy Resurrection. Already then the Church was hounded by a problem that besets it (that is, us) still. There’s a sharpness in Paul’s voice when he says: ‘I appeal to you: make up the differences between you’. For that is what the liturgical translation says. I’d like to challenge its choice of vocabulary. We modern Westerners like to make up our differences. For us, this is a matter of discussing our way to consensual arrangements, often by way of refined ‘compromise’, which is another term we like. Such pursuit of consensus evokes the image of responsible citizens gathered in council. And by all means: This is an excellent method when it comes to seeking practical solutions to societal issues.

Paul’s epistle is about something else, however. It is about the basis of our Christian confession. That to which the Apostle exhorts is not ‘making up differences’ in the sense that we should talk our way to a generally agreeable point of view. What he says, literally, is: ‘I appeal to you all to say the same [ἵνα τὸ αὐτὸ λέγητε πάντες]’. In other words: there should be one confession, for the confession is not something you construct, but something you receive, a revelation of God through the Church which calls for affirmation in grateful faith, not for majority decisions.

The background for this admonition is the Corinthians’ tendency to divide themselves into camps: ‘I am for Paul’, ‘I am for Apollos’, ‘I am for Cephas’. How typical this situation is! How instantly recognisable! We encounter it in our own time; indeed in recent times we have heard voices crying, ‘I am for Pope Francis’, ‘and I am for Pope Benedict’, while others shout, ‘and I am for Pope Pius X’. What a lot of nonsense. It is good for us to hear, and chew on, Paul’s satirical-rhetorical question: ‘Has Christ then been parcelled out?’ Of course he hasn’t. Neither should we, then, parcel out his Body. Instead we should pull ourselves together, ‘united in belief and practice’, ‘lest the Cross of Christ be emptied of its power’.

A gigantic statement: ‘Lest the Cross of Christ be emptied of its power’!

This is what it’s all about, when it comes to the crunch. God became man, walked among us and did good, taught us, suffered, died, and rose for us in order that that which was fractured should become whole. Division is the wages of sin. The first thing that happened after the fall was that the relationship between man and woman, created in view of one another, broke down. Then arose the feud between the protoplasts’ children. The first recorded death in human history, as Scripture recounts it, was a death by fratricide. Don’t forget that. We are conditioned, by sin, to be suspicious, to impose ourselves, to cut ourselves off, and to practise proactive aggression. These tendencies constitute sin. When the Church’s life is reduced to party politics, we let ourselves by pulled back into Cain’s and Abel’s clash out there in the open field. We live as if Christ’s cross was powerless. But what has become of us then, from a Christian point of view? Are we even Christians?

We might note two things in particular from today’s Gospel. The first concerns the very first word Jesus utters in his preaching. In our text it reads, ‘Repent!’ Which is fair enough. But in Greek the word is Μετανοεῖτε. Metanoia is to do with our perception of reality. Think of paranoia. It stands for a state of delusion in which we consider ourselves (or alternatively everybody else) to subsist in a parallel universe. Metanoia points upwards, the way metaphysics draws that which is visible and palpable into an eternal dimension. Paul provides an excellent paraphrase of the Lord’s call to metanoia when he writes: ‘Be transformed by the renewal of your minds’ (Rm 12.2). We, too, are called to see reality in a new light, God‘s light. That has to happen in real terms, in life the way it really is, not just in our heads.

It is significant, therefore (and this is my point number two) that the first disciples called by Jesus are two pairs of brothers. Scripture does not idealise family life. On the contrary. The relationship between brothers is often marked by rivalry, enmity and violence, from Cain and Abel to Jacob and Esau, Joseph and his brothers, the twin nations Israel and Judah, Absalom and Amnon, and so forth. Brothers surround themselves with competing bands of supporters. Situations arise in which the old tribal howls are heard, ‘I am for Paul’, ‘I am for Apollos’. When the Lord calls Peter and Andrew, then James and John, he says symbolically: ‘Enough of this! Henceforth brother shall not rise against brother; brothers shall unite under a single banner, bearing the mark of my Cross; and their fellowship shall be delightful.’

The Church, proclaimed the Second Vatican Council, was instituted to be ‘a lasting and sure seed of unity, hope and salvation for the whole human race’ (LG, 9). This unity is not – cannot be – a human project; such a project would be bound to fail. The unity has been won for us by Christ’s cross. Peter and Andrew both sealed their Christian testimony on a cross. At their own request, one was crucified upside-down, the other diagonally. Both emphatically wished to avoid giving the impression that their sacrifice was tantamount to Christ’s, which alone transforms, renews, and unites our world.

Let’s remember this in our daily life, not least in these days, when we pray for Christian unity. This unity will not come about through parliamentary debate, podium discussions, or questionnaires. It will come about in so far as we truly can say, ‘It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me’, and in so far as we are ready even to die for the sake of his name, firmly established in faith in his glorious resurrection. Amen.

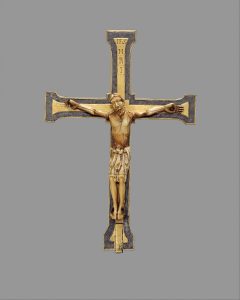

North Spanish Reliquary Crucifix from ca. 1125–75. Metropolitan Museum.