Words on the Word

3. Sunday of Easter: Confirmation

Acts 5:27-41: Obedience to God comes before obedience to men.

Revelation 5:11-14: To the Lamb be all praise, honour, glory, and power.

John 21:1-19: Du you love me?

Our first reading introduces us to a religious conflict which is also a political conflict (the two tend to go together) in Jerusalem shortly after the death and resurrection of Christ. The quarrel is about obedience.

Who deserves, and who can lay claim to, the obedience of another human being? The high priests consider the message of Jesus divisive and provocative. They have told the disciples in no uncertain terms to keep quiet. Peter and the apostles answer: ‘Obedience to God comes before obedience to men.’ This statement shows that their money is where their mouth is, so to speak. That commands respect. It also commands astonishment if, for a moment, we stop to reflect that the same group of apostles, a few weeks earlier, sat huddled behind locked doors ‘for fear of the Jews’ (John 21:19), that is, terrified of meeting the very same authorities they now openly challenge.

A couple of question present themselves naturally. What has happened to make the discouraged courageous? And what is this precious obedience about? I wish to reflect briefly on these two questions, especially in view of those of you who today receive the sacrament of confirmation.

What’s happened to the apostels. The answer can seem obvious? Oughtn’t a bishop to know? Between events — between the anxious waiting in concealment and the public dispute — Pentecost has occurred. The twelve have received the Holy Spirit. Surely it’s no wonder, then, that they’re courageous?

Oh yes, it it. And I wish to explain why; for this is a matter of great importance for you who are about to be sealed with ‘the gift of the Holy Spirit’.

The Spirit is not some sort of automatic potency. The Spirit is God himself; and God is no vague energy, he is a personal presence. To let another person into our lives, we need to make a conscious decision. We know that from our experience of friendship, perhaps even from the experience of enmity. It is quite possible to invade another person’s attention, and time, to get on their nerves. But a relationship of this kind remains external. To gain access to another’s heart, I need to be freely admitted; even as I am free to admit, or not, another person to my heart. Not even God almighty can force his way into my heart if I decide to close it to him. If I say No to him, he respects it. Our freedom at this level is absolute. No one can force us to love. No one can force us to be loved. And love, after all, is the foundation of our relationship with God, even as it is at the base of every friendship.

The gift of the Spirit presupposes the opening of hearts. For the apostles, this process takes place in the time between the crucifixion and pentecost; the time you and I are in right now, liturgically. Today’s Gospel gives us a sense of what happened. We find seven of the apostles gone fishing, that is, returned to what they were doing before their encounter with Jesus, which they now presume ended in a flop.

Yet there, at Lake Tiberias, they encounter the Lord. They see with their own eyes that he who had been dead is alive. His promise turned out after all to hold water. He is, in very fact, someone who can be trusted, even in matters that appear impossible. The relief of Peter and his friends is palpable. Yet within it floats a dark cloud. It is Peter’s cloud.

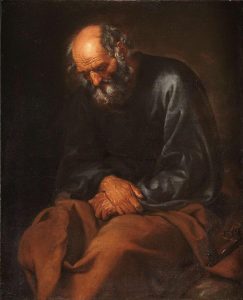

Peter can hardly forget that the last time he saw Jesus, the most important person in his life, his best friend, he had publicly said, not just once, but three times: ‘I’ve no idea who he is.’ Nothing is harder to bear than the consciousness that I’ve betrayed someone I love, and who loves me. How can Peter rejoice in the fact that Jesus is alive, and receive Jesus’s Spirit, when he knows he has let him down cruelly?

Jesus knows what goes on in Peter’s heart and how he suffers. He doesn’t accuse him: note that well. Note also that he doesn’t merely sweep the matter under an oriental rug. What he does do is this: he manages to touch Peter’s wound in such a way that it can heal. He asks three times, ‘Do you love me?’ Thrice Peter is enabled to annul his denial. John presents Peter to us as nervous, cowed, as if he were expecting a lash of the whip. What he encounters instead is mercy. ‘Mercy’ is one of those biblical and churchy words we use all the time. What does it stand for? Mercy is willingness to look on a man or woman realistically, without illusions, conscious of all their mistakes and faults, and yet to love them.

Here we touch something that is difficult for most of us. Most of us struggle to believe we can one loved. We suppose that we, in order to be loveable, must first become something we are not. Thus we make a mask for ourselves, a mask we show to others, trying to appear the way we think we ought to be. Our true face, which represents everything in our lives that makes us vulnerable, the things of which we are ashamed, we keep out of view. We think: well, if anyone saw that, they’d run a mile, and despise me into the bargain.

Peter finds, on behalf of us all, that it needn’t be like that. Jesus sees all his imperfection and loves him nonetheless. He shows him friendship. Thereby he lets Peter discover that he can still be a friend, that he’s able to love. This is the source of the courage Peter shows afterwards.

You know, this is precisely what the gift of the Holy Spirit is about: it is the experience of being seen and loved in truth, for what I am and for what I have it in me to become, in order, thus, to base my own life on live. Jesus calls the Spirit ‘Spirit of truth’. Today, my friends, you stand before God in truth pledging to found your lives on truth. God seals your purpose with his gift. You enter a covenant with him. May this covenant of confirmation be for you always a source of courage, confidence, strength, and joy!

When Peter talks about ‘obeying God’, he has this sort of loyalty in mind, not just a heap of rules. When life becomes serious, and it does, we need beacons to steer by, criteria to judge by. We need to tell the difference between black and white, truth and falsehood, good and evil. This challenge is relevant for all of us right now. Europe is at war. We hear threats which, just a few months ago, we thought the world would never hear again. No one knows what will happen. We are conscious of being surrounded by influences that which to manipulate, domineer, and deceive us. We must choose sides, choose whom and what to obey. This holds not least for you who are young. My own generation has been faced, and is still faced, with difficult choices. I dare say yours will be even more momentous. You need to know what you stand for.

Today you declare that you wish to live and do combat on the side of truth and mercy believing in the victory of the Cross, in the power of the Holy Spirit. You declare yourselves ready to receive the Spirit’s gift through the Church in the form of the cross I will shortly trace on the forehead of each one of you with holy chrism. Be faithful to the Cross! Believe in the promise it represents! That is my wish for you today. It is also my solemn exhortation. In the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, Amen.