Words on the Word

32. Sunday B

1 Kings 17:10-16: The jar of meal was not spent.

Hebrews 9:24-28: Christ, offered once to bear the sins of many.

Mark 12:38-44: She put in everything she had, her whole living.

Our second reading expresses the heart of our Christian faith with density. It calls for attentive reading. The redemptive action of Christ is presented in three aspects. First, we are told he offered up himself ‘to put away sin’. With this formula, the RSV translates the Greek verb ἀτίθημι quite literally, but we may get a clearer view of what it means by considering the Vulgate’s imaged, even poetic rendering, ‘ad destitutionem peccati’. On this reading, Christ’s Passion robbed sin of its resources, rendering it ‘destitute’, with no securities to hold on to. All spiritual and existential capital pertains henceforth to Christ’s cross, in so far as we let its grace take effect in our lives; in so far, that is, as we ‘bear’ the cross and seek to be conformed to it. The second aspect of Christ’s work follows on from the first: having accomplished his mission on earth, he is at work, now, before the face of his heavenly Father, where he ‘appears on our behalf’. He is our advocate and intercessor, the one who pleads our cause. Having shared the human condition — though without sin — he knows the fragility of women and men; he knows the trials to which we are exposed, the vulnerabilities we have to negotiate. These he presents to the Father with a plea for mercy. When, at the beginning of each Mass, we turn to the Lord and plead, Kyrie eleison, we ascend towards this dialogue of compassion between Father and Son, our prayers carried up by the Spirit. This cry for pity will resound until the end of the world, when Christ, as the third aspect of redemption, returns with glory to judge the living and the dead, to ‘save those who are eagerly waiting for him’. Our great task as Christians is to position ourselves within this dynamic of expiation, intercession, and impending judgement. How do we live in such a way? That is the question we must ask, to which the other two readings of our Mass in some ways provide an answer.

Both speak of widows who gave their all. The widow of Zarephath was affected, with the rest of Israel, by a drought brought on by the Lord in retribution for the people’s idolatrous excesses under King Ahab. The widow, being just and god-fearing, suffered as an innocent, paying the price for the evil done by others. Pain endured for the wickedness others have committed is rarely ennobling. Little is more likely to induce righteous indignation bearing fruits of bitterness. The widow resists this destructive tendency. Even though the famine of the land was sent by God, she believes in God’s goodness and for his sake consents to share her last morsel of food with a stranger, in obedience to Mosaic law. This act of faith on her part (a faith we can surely call heroic) enables a miracle of grace to take place. Having given everything she had to live on, she finds that more is provided, her meal-jar and her oil-cruse filling up by divine intervention. Offering up her livelihood that someone else might live, she finds that life is bestowed, as free gift, in abundance.

The widow in the Gospel is likewise unsparing. To give glory to God and to provide for the poor of the land, she ‘put in everything she had’ as an offering to the Lord. A case could be made for a still more radical rendering. According to the Greek text, she gave ἐκ τῆς ὑστερήσεως αὐτῆς, which means literally, ‘out of her want’, ‘out of what she didn’t have’. A good financial adviser would call her reckless, irresponsible — in fact, he would probably ask that she be placed under tutelage, as being unable to administer her resources. Christ portrays the situation differently: this, he tells us, is the way to live, to give without counting the cost, to surrender ourselves as an oblation, to risk poverty, death even, to abide by the Law’s injunction of charity, to be supremely free, not only with regard to our possessions, but with regard to our life, ready to lay it down in the sure hope that, in Christ, we will take it up again. The sublimely theological vision of Hebrews becomes, by means of these examples, a lesson to live by, by which to construct our lives, individually and in common.

In the collect this week, we pray to be kept ‘from all adversity, so that, unhindered in mind and body alike, we may pursue in freedom of heart the things that are [God’s]’. Real adversity, our readings tell us, is not illness, poverty, and death, though these are bitter. Real adversity is resistance to Jesus’s call to give all, to seek our riches in things of this earth that, on the Cross, he despoiled, instead of following the oblative logic of the Passion, to be conformed to Christ and so made one with him. If we dare to adopt this perspective on life — and courage is called for! —, we find that every moment provide opportunities to make a choice for or against salvation, for or against Christ’s cause. To live in this way is demanding, but it’s the way to be set free, to be rooted in truth, in reality the way it really is — and where freedom and truth intersect, joy is never far away. May God grant us the widows’ great-souled, generous grace so that we, like them, may be made worthy of the promises of Christ. Amen.

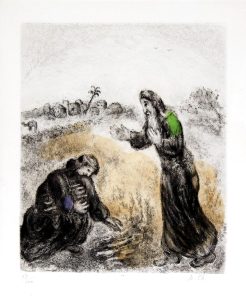

Marc Chagall, Elijah and the Widow of Sarepta. From his ‘Desseins pour la Bible’.