Words on the Word

5. Sunday A

Isaiah 58.7-10: Do away with the clenched fist.

1 Corinthians 2.1-5: I came not with any show of oratory.

Matthew 5:13-16: You are the salt of the earth.

For us, salt is a condiment we use to enhance — or to obliterate — the taste of food. Most of us eat too much of the stuff; we may have been told by our doctor to cut down. The proclamation, ‘You are the salt of the earth’, can resound in our diet-conscious ears a little ambiguous. Salt is something we like, but should have less of. So we must put our Lord’s words in context. In Antiquity, salt was not primarily about flavour. It was used, in the absence of refrigeration, to preserve food. Also, it was known to be a prerequisite for stable health. The human body cannot function without some sodium. An absence of salt leads to cramps, nausea, and dizziness. In extreme cases, it can provoke coma and thus be a cause of death.

Years ago I read the story of the Russian Lykov family who, as persecuted Old Believers, fled secular society in 1936 and settled in the Khakassian taiga, as far as it is possible to get from the sea. There they formed a separate enclave in which, for decades, the lived secluded, having no contact with other human beings. When geologists discovered the family in the late 70s, they asked what had been the most difficult aspect of living so entirely cut off from society. One would have thought: the relentless solitude, the lack of amenities. But no, the answer was immediate: what had caused them most hardship was lack of salt. Sodium-deprivation had impacted gravely on the solitaries’ health.

In Latin, the very word for health, salus, has salt, sal, in it. Even though it is not a matter of exact etymology, the link is suggestive. The wages a person needs to live, his salary, is literally ‘saltmoney’, salt being needful for subsistence. In the sixth century, Moorish merchants in Africa traded salt ounce for ounce for gold.

What Christ our Lord asks of us, then, is not just to add a little seasoning to the world, as if to render the world more palatable. Our task is to provide the world with something essential which it needs to live and thrive, something without which it languishes and dies. That something is not ours; it is his, indeed it is himself, given through us. Do we hand ourselves over to him utterly so that we may become salt, that is, so that it is no longer we who live but he who lives in us? On that question depends the efficacy of our testimony and mission, as does, quite simply, our fitness for purpose. Are we fit for purpose?

Our reading from Isaiah gives us criteria by which we may assess how we are doing. Some are positive: they indicate actions we should carry out: ‘Share your bread with the hungry, shelter the homeless poor, clothe the man you see to be naked, and do not turn away from your own kin.’ No one would quarrel with these injunctions. But they may seem a little abstract. Living as we do in a welfare society, we do not readily see hunger, homelessness, nakedness. So we respond from a distance, wiring a bit of money to charity overseas. This is excellent, of course; but there may be scope for more. Here in Trondheim there is poverty. Our Caritas volunteers can testify to it. There is scope for corporate works of mercy. Further, we might apply the Biblical principles more broadly. The counsel to ‘clothe the naked’ makes me think of H.C. Andersen’s tale about the Emperor’s new clothes, a parable that speaks to our image-conscious, vanity-prone times. Even in the Church there is a risk that hypes replace substance, that we mistake emptiness for content, and start praising nudity as the height of modern elegance. So who knows? Perhaps a further way to honour Isaiah’s words, and so to have salt in us, is by way of naming such nakedness when we see it in order not to leave it exposed, especially now, when the weather can be fierce.

The prophet’s negative commandments — his list of things not to do — is also worthy of close notice: ‘do away with the yoke, the clenched fist, the wicked word’. The image of the clenched fist is powerful. It evokes tightfistedness in the conventional sense of stinginess. We may ask ourselves: Am I a credible follower of the Lord who gave everything, pouring himself out to the point of nothingness, in order that we might live? The tight fist also speaks of violence, suggesting a readiness to punch if need be. And we might ask: Do I carry aggression, active or passive, into my relationships? If so, why? On this score it is worth conducting an examination of consciousness and conscience on a regular basis. For nothing more effectively obscures the light, little does more to make salt tasteless, than unacknowledged rage. So let’s watch those clenched fists, release the pressure and be bearers of peace. In such simple ways we can heed the Lord’s commandments to be salt and light in fact, not just notionally. And after all, our faith is about real life — about life renewed, transformed, and sanctified in Christ. Amen.

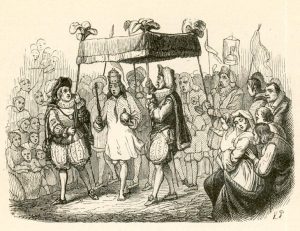

The Emperor’s new clothes. Illustration by Vilhelm Pedersen, Andersen’s first illustrator (illustration from Wikipedia). To clothe the naked in this context is to preserve those misled by vanity from making themselves silly and so from compromising not only their own dignity but the dignity of the cause they represent.