Words on the Word

5. Sunday of Easter

Acts 14.21-27: We all have to experience many hardships.

Apocalypse 21.1-5: I, John, saw a new heaven and a new earth.

John 13.31-35: Love one another just as I have loved you.

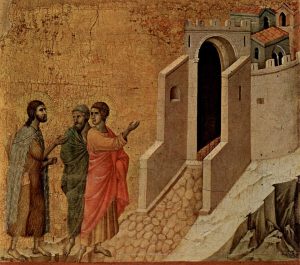

The period between Christ’s resurrection and his ascension into heaven was for the apostles a time of remembrance. They spent it turning over in their minds all that he had said and done, and the prophecies about him, to draw this into a coherent whole in the light of Jesus’s victory over death. We find the most explicit description of this process at the end of Luke’s Gospel, in the story of the wanderers to Emmaus; but it is implicit in the other resurrection narratives, too.

The period between Christ’s resurrection and his ascension into heaven was for the apostles a time of remembrance. They spent it turning over in their minds all that he had said and done, and the prophecies about him, to draw this into a coherent whole in the light of Jesus’s victory over death. We find the most explicit description of this process at the end of Luke’s Gospel, in the story of the wanderers to Emmaus; but it is implicit in the other resurrection narratives, too.

By means of the liturgy, the Church draws us into this apostolic work of assimilation. It always moves me that she, our Mother, lets us re-read, now in Eastertide, words Jesus spoke on the eve of his sacred Passion. The grandiose teaching of the thirteenth chapter of St John strikes chords now that differ from those struck when we heard it last on Maundy Thursday.

‘Love one another; just as I have loved you, you also must love one another.’ When this ‘new commandment’ was put forward in the Upper Room, the apostles connected it first and foremost with the gesture Jesus had just performed: the washing of their feet, including those of Judas, now gone into the night to betray him.

Again and again the Lord had given an example of selfless service, turning away from his own concerns to attend to the troubles of others. The eleven will have thought of the meeting with the haemorrhaging woman, of the healing of the lame man lowered through the roof, of the raising of the son of the widow of Nain. They will have recalled the detachment required when Jesus, weary, had gone apart to rest awhile, only to find on arrival that a crowd awaited him: no word of complaint was heard, no gesture of irritation seen; instead he turned towards the interlopers cordially, all theirs. Truly he had taught them what charity looks like, embodying a paradigm that set for them, as it sets for us, a standard towards which we must strive.

The fact of Jesus’s resurrection raises our reflection into another dimension, however.

The ethical demands of Christian love remain. They are non-negotiable, timeless. By them we shall be judged. The parable of the goats and sheep make this clear. Still, ‘love’ in Biblical language stands for something more. ‘God is love’ (1 Jn 4.8): St John affirms what Scripture shows from the beginning. Divine love is manifest in acts of kindness, as when the Lord, sending Adam and Eve forth from Eden, clothes them in garments of skin; when he consoles Hagar in the desert; or sends ravens out to feed his contrary and hunger-striking prophet Elijah. But the love that is God’s Being can terrify, too. It is at work in the Egyptian plagues, in the downfall of Og, in the censuring of David after his calculated adultery with Bathsheba.

Ordinary parlance tends to assume that the opposite of love is hatred. But no. Hatred can contain a passion that does not contradict love but is rather love’s inverted reflection.

Élie Wiesel, a survivor of Auschwitz, memorably said that the opposite of love is indifference, the carelessness that may not itself pursue the destruction of another — that may not actually put banana peel before the blind or denounce persecuted strangers — but does not bother when others do, just coldly drawing the curtains or looking away. In this manner of seeing, love comes to an end in the extinction of compassion, when individuals or collective entities, communities or even states, pursue no other goal than self-preservation while in fact sabotaging their own endeavours, in as much as ‘whoever seeks to save his life will lose it’ (Mt 16.25).

In Biblical terms, the opposite of love is death. God is love in as much as he is the principle of life, desiring things and beings to exist for the sheer delight of it, without expectation of gain. To love as God loves (‘just as I have loved you’) is to nurture the existence and thriving of others while having no truck with death, resisting anger, bitterness, spite, all those mortiferous passions that put out grace’s flame and make us ungracious, causing us to subsist in a kind of living death, for it is quite possible to have a regular pulse and a normal digestion yet to be soul-dead.

By letting himself be nailed to the wood of the cross, by his wounds and holy dying, by his harrowing of hell and glorious  resurrection, Jesus despoiled the reign of death that had held sway since our first parents chose it.

resurrection, Jesus despoiled the reign of death that had held sway since our first parents chose it.

‘Death with life contended’, sings the Easter sequence. It goes on: ‘Combat strangely ended!’

Indeed it does seem weird, at first sight, that the cross, an instrument of cruel execution, should be for us the emblem of life restored — but only insofar as we forget that that which died on the cross was death itself, while life was proved invincible. ‘Love is strong as death’, an ancient bard prophesied in the Song of Songs. His proposition was borne out on Calvary and, thereupon, within the grave of Joseph of Arimathea, where our lord rose from the dead.

It is this death-defying love we must invite into our lives, that it may break our alliances with sin, death’s enabler, and let whatever dead bones we carry stir and recompose themselves to make of us women and men fully, not just half alive, epiphanies by grace of God’s glory.

‘I saw’, we have heard the Seer of Patmos say, ‘a new heaven and a new earth’. That reality is not for the end of history only; it is to be inaugurated now, in our hearts, yours and mine.

Amen.