Words on the Word

7. Sunday C

1 Samuel 26.2-23: I would not raise my hand against the Lord’s Anointed.

1 Corinthians 15.45-49: We will be modelled on the heavenly Man.

Luke 6.27-38: Love your enemies.

Today’s collect bids us accomplish in word and deed that which is pleasing to God. All of us wish to do that, in principle. But how?

The collect tells us: by constantly keeping in mind rationabilia — ‘semper rationabilia meditantes’. The Latin ratio gives us our word ‘rational’, which has to do with reason. Think of John Paul II’s encyclical from 1998, Fides et ratio, an essential text it is good to re-read from time to time.

The pope insists that faith and reason presuppose each other. Both issue from God’s Word. We who have faith, must comprehend what we believe in. Only in this way will we bear witness comprehensibly.

Likewise, reason needs to be perfected by faith in order to let us reach the depth of insight, so to intuit, not only how the universe works, but what the universe means. In this regard we often fall short.

For us, now, reason has to a large extent become a synonym for reasonableness, which we think of as calculable. When we speak of acting reasonably, don’t we tend to speak of action that is to our advantage? It isn’t reasonable to invest in shares that will lose value.

Precisely these days we ought to think carefully about that which is presented to us as ‘reasonable’. We are daily faced with pretensions to a new world order resting on the notion that a ‘reasonable’ solution to global tension is businesslike. It presupposes that everything, and everyone, has a price. What counts is to work out how much you are willing to spend.

We must be conscious of where such ‘reasonableness’ can lead, not least when we are no longer one of the negotiating parties at table, but the negotiated object — for a true businessman sees neither peoples nor persons, only objects of relative worth.

For us Christians, reasonable behaviour is steered by other criteria. We view purely pragmatic reason critically. We know from experience, painful experience, how ready we human beings are to use ‘reason’ as a means to justify ourselves. What a Christian wishes is to see the world with God’s eyes, in the light of a reason that transcends our own, conforming us to truth. For us the criterion of action and decision-making is the Word of God, his Logos, incarnate of the Virgin Mary. Christian reason is about putting on the mind of Christ.

Today’s Gospel shows us how far removed this mindset is from calculating self-interest.

Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who treat you badly.

Is this not bonkers? Where would society go, should the offended sit around and blow kisses at offenders, should the violated bow down in reverence before their attackers? Before we indignantly shut our Bible with a bang, though, let us consider what our Lord is actually saying.

The first thing we must establish is this: Justice is a Biblical imperative. Bullies receive short shrift in Scripture, from the beginning of Genesis to the end of the Apocalypse. The Lord casts the mighty down from their thrones and lifts up the lowly; he gives food to the hungry; sends the rich empty away. Daily we repeat these promises when we sing Mary’s Magnificat at vespers. The revolutionary aspect of Christianity is real. But the revolution must be guided by light, not darkness. How often has history not shown that an oppressed man or woman, once in possession of power, turns in turn into a brutal oppressor? Bitterness and hatred blind us, poisoning even our noblest purposes.

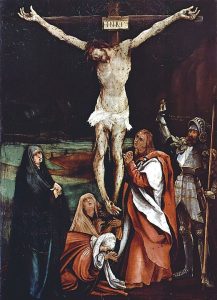

That is why Christ bids us drive hatred out of our hearts. He bids us this who, innocently crucified, prayed: ‘Father, forgive them!’ And remember: ‘He who says, “I am in him”‘, who wishes to live in Christ, ‘must walk as Jesus walked’. Praying for his enemies, Jesus did not simply cancel their misdeed. Any sin, any act of violence, leaves a wound that must be repaired. Tradition tells us that one of the soldiers keeping watch on Calvary came to faith when Jesus died. This soldier, Longinus, spent the remainder of his life doing penance. The Lord’s grace, his love shown to an objective foe, illumined this Roman centurion as to his own injustice.

To love our enemies, to do well to those who hate us, is an unsentimental business. It is not a matter of warm feelings. It is a matter of wishing that the blind be given sight, that the lost be saved. In order thereby to extract the sting of hatred from our heart.

Let me give you a little example from experience. Ten years ago I was conducting a visitation in Cameroon. A long, tiring day had come to an end. We had sung compline. I had gone to bed. Then I suddenly heard a great noise of people shouting. It went on and on. Indignant, I thought: ‘Who on earth is in charge here?’ Then I realised: I am in charge here.

I got out of bed, put my habit on, went into the cloister. A brother was lying there, bleeding from his head. He had been attacked with a bottle. Another brother had been shot through the chest: he was already on his way to hospital. The two of them had been attacked by bandits. These armed people were still hiding in the woods surrounding us, in the middle of the countryside.

I sent the most valiant monks out to keep watch. I gathered the others in church to pray for our shot brother’s survival. There, before the Body of the Lord, I felt my own anxiety. I was distracted, angry. Then I suddenly heard one of the monks pray aloud: ‘Lord, look graciously on these men of violence! Show them your love, Lord! Let them not be lost!’ I admit that my own thoughts were in another register; but I realised what it means to respond as a Christian even when exposed and at risk.

To call down God’s life-giving power on those who serve the cause of death, to nurture a hope that goes far beyond what is reasonable: this is what it means to love one’s enemies, to begin to be a Christian. It is a prayer, and a form of reason, our world today needs badly. Amen.

Præsta, quæsumus, omnipotens Deus,

ut, semper rationabilia meditantes,

quæ tibi sunt placita, et dictis exsequamur et factis.

Mathias Grünewald’s account of Jesus’s Passion with the Mother of God, Saint John, the holy women – and Longinus, the solider who had pierced Christ’s side and who underneath the cross found faith.