Words on the Word

Ash Wednesday

Joel 2.12-18: Let your hearts be broken.

2 Corinthians 5.20-6.2: Be reconciled to God!

Matthew 6.1-18: Your Father sees all that is done in secret.

The ritual after which Ash Wednesday is named has immediate symbolic impact. By receiving the ashes, we own our creaturely fragility. ‘I am but dust and ashes’, Abraham exclaimed, interceding for Sodom, ‘should I presume to address God?’ The ashes stand for repentance, too. The people of Nineveh covered themselves and their cattle with ashes to repair past pretension. And of course the ashes represent our awareness that one day we shall die. Nothing is deader than ashes. Nothing grows in it. It is impressive, a sign of healthy realism, that we all together once a year, in peace, publicly recall that we are dust and shall return to dust. Thereby much else falls into place.

The ashes we use liturgically aren’t just any old ashes. They’re not just raked out of the fireplace. It is a devout tradition that the ashes of Ash Wednesday come from the burning of last year’s palm branches, received on Palm Sunday. Thereby we show that we start afresh. We begin our preparation for Easter as if setting out on this journey for the first time. We do not ape by way of repetition predictable gestures; we participate in a salvific reality that is and remains for ever new, powerfully present.

The ashes we use liturgically aren’t just any old ashes. They’re not just raked out of the fireplace. It is a devout tradition that the ashes of Ash Wednesday come from the burning of last year’s palm branches, received on Palm Sunday. Thereby we show that we start afresh. We begin our preparation for Easter as if setting out on this journey for the first time. We do not ape by way of repetition predictable gestures; we participate in a salvific reality that is and remains for ever new, powerfully present.

I’d like to consider more closely a particular aspect of the connection between Palm Sunday and Ash Wednesday. Christ’s entry into Jerusalem appeared a triumph. Great expectation surrounded him. People cheered, even those who hardly knew who he was. Crowds are like that. They let themselves be swept along and don’t think deeply unless they really have to. Daily life is often dull. It is a relief, a welcome distraction, when something extraordinary happens. Who knows? Changes are perchance afoot that will may make my life more comfortable, less monotonous, giving me a sense that I count? In aid of such a cause I will gladly shout hurrah, hosannah, or any other slogan, depending on circumstances. The palm branches express support for today’s promising hero, whatever his name is. People waved them then, no doubt, to hail him of whom it was said that he came ‘in the name of the Lord’, but no less to show that they were on the winning team. When a public figure with a messianic message appears, we like to be on the side of strength. We wish others to see that we are, so acquire the signs of allegiance we need: a palm branch, a flag, a baseball cap, perhaps. Our hosannah must be visible! What’s the point of a retweet or like if no one notices what or whom I acclaim?

But God help us — how brittle such confessions are! Those who on the first day lionised the Son for David turned, on the sixth, into a snarling band with raised clenched fists shouting, ‘Crucify! We have no king but Caesar!’ No one then swung last Sunday’s palms. By burning precisely these branches today, by being signed with their ashes, we ascertain the limits of rhetorical excess. No society, sacred or secular, can endure over time on the basis of slogans. A heated atmosphere my corral people for a while, especially if they have a common enemy, real or imagined, to hate; but in order to unite people durably more is required, especially when support for a cause, or person, calls for sacrifice. Trust is needed, then, and fidelity, pondered conviction and, let’s risk the word, love. No sustaining unity issues from disdain.

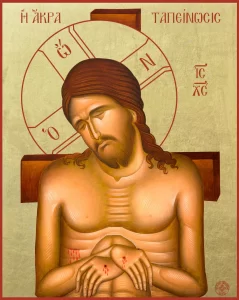

Our world right now in many respects appears unhinged. A political and cultural landscape is being reconfigured by bulldozers. It seems that good sense and cultivated ideals belong to a past stage of evolution; that absolute criteria for action or decision no longer exist; that any human or societal contract takes the form of transactions of calculated gain; that what counts is to howl with the wolves; and that rhetoric, even based on untruth, has the last word because all other words are deafeningly silenced. It is thought-provoking, then, to receive the ashes of yesterday’s hosannah while we fix our gaze on the Word made flesh, who did not consider his likeness to God a thing to be grasped but emptied himself. Silently he beheld the crowd’s fickleness with  penetrating clarity, yet without anger. His purpose was to pull people out of the deadly swamp of bitterness to inaugurate a new humanity formed in his image, that hell-gate-resistant, blessed, at once so deeply human and patently supernatural fellowship to which we are graced to belong, which with gratitude we call the Church.

penetrating clarity, yet without anger. His purpose was to pull people out of the deadly swamp of bitterness to inaugurate a new humanity formed in his image, that hell-gate-resistant, blessed, at once so deeply human and patently supernatural fellowship to which we are graced to belong, which with gratitude we call the Church.

Today we embark on spiritual battle in Christ’s name. Resolutely we distance ourselves from illusion and turn towards the Real. We don’t want to build our house of sand, but on rock. We must take God’s commandments seriously: the commandment to call down God’s mercy on all people with weeping, presupposing our capacity for compassion; the commandment to foster justice and truth; to let ourselves be reconciled to God by renouncing self-righteousness, confessing our sins, not or neighbour’s.

There’s much talk at the moment about epochal chance. I think the hypothesis well-founded. Let me, though, stress this: it is not deterministic. Nothing is written in the stars. Whether the epoch on whose threshold we stand will be better or worse, hostile to God or in the service of Christ, depends on us. We are, as Paul says, ‘God’s collaborators’.

We know ourselves, so have reason to reflect: this is a pretty daring move on God’s part. It’s how he works. His faith in us is staggering. Do we show ourselves worthy of it? ‘Turn to me with an undivided heart’, says the Lord — only to add that a heart, to be whole, must first be broken in repentance. ‘Now is the favourable time’. This is the day of salvation, if we let it be. We carry great responsibility. Amen.