Words on the Word

Assumption of Our Lady

Apocalypse 11:19; 12:1ff.: The ark of the covenant could be seen in the sanctuary.

1 Corinthians: All men will be brought to life in Christ, in their proper order.

Luke 1:39-56: All ages will call me blessed.

The Apocalypse places great demands on the reader, never mind the expositor, of Holy Scripture. Even a short passage like the one we have just heard is so full of imagery that we can feel overwhelmed.

On centre stage is a woman great with child, adorned with the moon, crowned with stars. She engages in battle with a dragon set on slaying her progeny. It is at once a single combat and a war that affects the whole cosmos: by a twist of its tail, the dragon causes a third of heaven’s stars to fall.

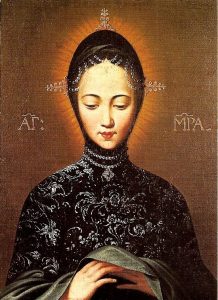

The woman is known to us, of course. From earliest times, believers have recognised her as Mary, the mother of the Saviour, who stands thus, star-crowned, in countless homes and shrines throughout Christendom. It is a beautiful image: a serene female presence poised as the guarantee that light will outshine darkness, that purity and truth have greater strength than all evil’s dark stratagems. This interpretation of our reading is legitimate and true. It is not, however, exhaustive.

The woman’s duel with the dragon must not make us forget the image, which, in our reading, forms a backdrop to it. When the curtains open, what first appears is the ‘sanctuary of God’ and, within it, the Ark of the covenant. If we look closely at the liturgy for the Assumption, we find traces of the Ark everywhere. Pictorially it is a less alluring symbol than the cosmic lady. An ark, after all, is just a box. Theologically, though, it is a sign full of splendour. Let us consider what it stands for, what it means.

The woman’s duel with the dragon must not make us forget the image, which, in our reading, forms a backdrop to it. When the curtains open, what first appears is the ‘sanctuary of God’ and, within it, the Ark of the covenant. If we look closely at the liturgy for the Assumption, we find traces of the Ark everywhere. Pictorially it is a less alluring symbol than the cosmic lady. An ark, after all, is just a box. Theologically, though, it is a sign full of splendour. Let us consider what it stands for, what it means.

The construction of the Ark was revealed by God on Sinai during the epiphany that forms the core of Israel’s faith, when Moses and Aaron stood before the Lord in the cloud of glory while the people below were told to wait in awe-struck wonder. The Ark was to contain what the Bible calls ‘the testimony’: tablets on which God, with his finger, had traced the terms of his covenant of mercy with mankind. The ‘testimony’, though, is not primarily the inscribed slabs as sacred objects. What is testified more essentially is God’s faithfulness, his abiding Presence among his people. That is why the Ark, as well as being a container, is a throne. On top of the Ark, the Lord told Moses, ‘you shall put the mercy seat; there I will meet you; I will speak with you of all that I will give you in commandment for the people of Israel.’ Over and beyond being a reliquary, the Ark is a sacrament of God’s Presence, a manifestation of his being there, in our midst.

The Ark was built and placed in its tabernacle. Following rites of consecration, the glory of the Lord descended upon it, resting on the mercy seat, hovering above the Ark. A cloud by day, a fire by night, it remained in the sight of the people. When the cloud was taken up, Israel would go onward. When it wasn’t, they stayed where they were, in the Presence. Thus the Ark was Israel’s guide on its journey home from exile. It was the first to cross the Jordan, to enter the land of promise. What happened to it next?

A scandal, a great scandal. Once settled in Canaan, the people had other things to think about: earthly concerns, the pursuit of wealth and pleasure. They forgot about God in their midst. By the time of Samuel, the Ark dwelt in the provincial shrine of Shiloh, surrendered to the corrupt ministrations of Eli’s sons. Hardly anyone thought of it as a sacrament any more. It was reduced to the status of a box of charms, brought into battle as a talisman, then lost to the Philistine army. When it was eventually regained, it was simply put in storage in the house of one Abinadab, in the hill country of Judah. It stayed there until David, the restorer of faith, brought it up to Jerusalem, where, around it, Solomon built the Temple.

In the Vigil Mass of the Assumption, the first reading, from Chronicles, tells how David brought the Ark into his city with solemn liturgies. Standing before it, he blessed the people and told them (as we sing in a Psalm), ‘the Lord has chosen Zion, here he has chosen to live’.

It is wonderful that, in today’s Gospel reading, we find Mary treading the very paths the Ark took then, out there in the hill  country of Judah. She retraces its steps, as the life of God stirs within her, her heart bursting with song. A living tabernacle, she carries the Lord to faithful Israel. She is the bearer of a Presence so wonderful, so great that it takes the greatest of the prophets to reveal it. Brought close to Jesus hidden in Mary’s womb, Elizabeth’s child ‘leapt for joy’. Lest the reference should elude us, St Luke takes care to use the same verb the Greek Old Testament employs in an Exodus Psalm that speaks of hills ‘leaping like rams’ in the Presence of the Lord leading his people out of exile.

country of Judah. She retraces its steps, as the life of God stirs within her, her heart bursting with song. A living tabernacle, she carries the Lord to faithful Israel. She is the bearer of a Presence so wonderful, so great that it takes the greatest of the prophets to reveal it. Brought close to Jesus hidden in Mary’s womb, Elizabeth’s child ‘leapt for joy’. Lest the reference should elude us, St Luke takes care to use the same verb the Greek Old Testament employs in an Exodus Psalm that speaks of hills ‘leaping like rams’ in the Presence of the Lord leading his people out of exile.

What was prefigured by the Ark is realised in Mary. She is, in the words of the Loretan litany, ’the seat of wisdom’, ‘the vessel of honour’, and of course, the true ‘Ark of the covenant’. May we be attentive to the mystery she carries. Where she leads, may we follow.

Today reminds us that we have not here an abiding city. The exodus continues. We are on the way home. The Ark has gone before. It beckons, fire by night, a cloud by day. Mary awaits us at our journey’s end, the heavenly Jerusalem. With eyes set on her, we may hope to get there.

O Mary, ‘cause of our joy’, leave us not until, with you, we reach home and behold God’s glory face to face. Keep us faithful to the testimony you were chosen to bear.

Amen.

Rubens’ Assumption, now in the Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf.