Words on the Word

Christmas Day

Isaiah 52:2-7: How beautiful are the feet of one who brings good news.

Hebrews 1:1-6: He is the radiant light of God’s glory.

John 1:1-18: He was with God in the beginning.

Each year on Christmas Day the Prologue of John washes over us like a thunderous waterfall. The first two Christmas Masses, at midnight and dawn, are narrative in character. We follow the circumstances of Christ’s birth among the shepherds in the field, then in the stable, surrounded by damp hay and the smell of animals. We stand as witnesses.

Much Christmas devotion is focused at a horizontal level, face to face with the mystery. This is good. By the incarnation God entered our horizontality, measurable in time and space. That is where he meets us. The Church’s early preaching insisted on this fact. It seemed incredible, and scandalous, that God should come to us on our terms. So this was rehearsed again and again.

These days we live with the opposite tendency. We take the homely, companionable Jesus for granted. It is natural for us to relate simply to him. We call him our brother, our friend. We are right to do so: these titles are Biblically grounded. But do we sufficiently remember that he is also our eternal Lord, God from God, Light from Light?

‘In the beginning was the Word’, writes John.

What’s a word? Formally speaking a word is a combination of letters or sounds capable of rendering sense. Not all words make sense on their own. They presuppose combinations with other words. But each word does mean something. Words enable us to order our experience and to share it.

To deprive a man of the use of words is to do violence to him. One of the first things totalitarian regimes will do is to restrict speech and outlaw vocabulary.

I have a tattered old book that used to belong to my grandfather, who was a prisoner in the Nazi camp of Grini during the War. The book is a collection of speeches given there by Francis Bull, a man of letters, during the Second World War. There were words that, in that context, it would have been impossible to use: ‘freedom’, ‘resistance’, ‘king’, and so forth. By using them nonetheless, or by finding clever ways of suggesting them by means of other words, Bull kept the other prisoners’ courage up. He kept alive a flame that otherwise might have been blown out by the icy wind of violence.

When John proclaims that the Word become flesh, the Word we revere in the manger, was ‘in the beginning’, it is to show that the Child born of Mary embodies the origin of all things. The Word became flesh not just to run a redemptive errand but also, and not least, to show us what our existence means, where we come from, the goal we are called to reach.

We read that ‘all things came to be through him’. It is literally true that he, by becoming man, ‘came into his own’.

When in daily life we purchase a gadget or other — a mixmaster — we are told to read the user’s manual. We need to know how the equipment is intended to work in order to use it well. Else we risk ruining it. If we come back to the shop with a wreck and it turns out we have used the thing wrongly, trying to mix cement with a Kenwood, the attendant will scoff and the shop’s warranty will do us no good. The accident was our fault.

The Word became flesh to display human nature in a perfect prototype, exactly as it was intended to be. The Producer demonstrates it. He challenges us to look for ourselves in him, and for him in us. He asks us to follow his example. We are called to resemble Christ, not primarily to get a pat on the back and a nice prize in the form of eternal life; we are called to resemble him because he, and only he, can show us who we really are. If we follow other paths, our nature will not work optimally. We may even risk doing it lasting damage.

To be a Christian is to surrender oneself into Jesus’s hands to be formed by them, to be repaired when needed — and to be ennobled. If only we would share God’s ambition on our behalf!

The Church knows it and spells it out. Think of the audacious prayer with which this Mass began, an expression of our dearest Christmas wish:

O God, who wonderfully created the dignity of human nature and still more wonderfully restored it, grant, we pray, that we may share in the divinity of Christ, who humbled himself to share in our humanity..

The human being is wonderfully made. The working of our body is a mystery great enough — but what are we to say about our mind, our soul, of everything we are equipped to know, enjoy, and suffer by?!

‘I will praise thee’, says a Psalm of David, ‘for I am fearfully and wonderfully made’. It’s a good phrase. Fear and wonder often coincide as we grow in self-knowledge.

So yes, the way we are made is amazing. But it will be surpassed, we are told, by our remaking in Christ. What we are of ourselves is as nothing compared to what we have the potential, in him, to become. If we dare to pray for a share in his divinity, it is because he desires to share it with us. The Word that was in the beginning is not external to us. The Word is the agent of our inward renewal. One and the same Word works in our soul by grace and holds the universe together; the Word that became flesh and was laid in a manger is that same Word that created the stars and still guides them. The ordered immensity of the cosmos is an image of the height a Christian is called to reach.

We can aim for such heights if we have the courage to follow John. Not for nothing is his emblem the eagle. John soars in the vast expanse of heaven, apparently immobile but in reality sustained by vast spiritual force.

John illumines the Gospel with glory. And he assures each of us: the Lord’s purpose for you is for your to become glorious, a new, infinitely beautiful creation in Christ, a bearer of eternal light into time’s night.

This does not mean that our faith becomes abstract and theoretical. No one sums the Christian condition up more concentratedly than John. ‘He who loves me’, says Jesus through John, ‘must keep my commandments coherently’. The commandments are immense: ‘Abide in me’ — let nothing, no one, separate you from the grace of Jesus; ‘Love one another’, unto death if need be; ‘Receive the Holy Spirit’, that your life may became the Spirit’s holy temple.

God was born like us and dwells among us to make us like him.

Grateful for his confidence in us, let us live in a manner worthy of him.

Amen.

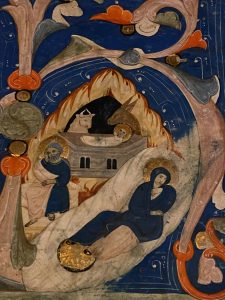

Initial from an Antiphonary produced in Bologna in the early 14th century, now in the Fitzwilliam Museum