Words on the Word

Christmas Midnight Mass

Isaiah 9:2-7: This is the name they give him: Wonder-Counsellor.

Titus 2:11-14: While we are waiting in hope.

Luke 2:1-14: Caesar Augustus issued a decree.

Before the Holy Family, the shepherd or the angels enter the scene, the Christmas Gospel records an historical event. ‘Caesar Augustus issued a decree for a census of the whole world to be taken.’ The census plays a key role in the narrative, dramatically speaking. On account of the imperial instruction that Joseph set out, with his highly pregnant wife, from Nazareth to Bethlehem. Thus was fulfilled the prophecy we read at Christmas: ‘But you, O Bethlehem Ephrathah who are little to be among the clans of Judah, from you shall come forth for me one who is to be ruler in Israel.’

Here already is evangelion, that is, ‘good news’: the accomplishment of God’s salvific design is rendered possible by a secular body that hardly knew what ‘salvation’ meant. When, with a sigh, we consider the secularisation of society, let’s be mindful of this. God, who made everything from nothing, can very well use atheistic institutions, too, for his blessed purposes.

For a long time it was thought that the census was a Lucan invention. No reference was found in historical sources. It was a matter, it was said, of retrospective fake news. Then something interesting happened. An English archeologist had the idea of publishing an inscription from a temple in the town of Angora, which we now know as Ankara. The text was a memoir Augustus had had written when he approached his 80th year, full of noble and heroic deeds. Among them is a mention of three censuses, the middle one performed ‘while Censorious was consul’, that is between 8 BC and 2 AD. And so Luke’s account was confirmed. It is funny to think that the historicity of the Gospel was vindicated from proof found in Erdogan’s capital. As I’ve remarked: God can use everything and is infinitely more creative in his enterprises than either you or I.

For Luke, two models of society meet in Bethlehem. The emperor unites the civilised world under the emblem of the Roman eagle. The Virgin, in secret quietness, bears him who would unite all peoples in his Body. The world Augustus formed enabled the message of Jesus to spread disconcertingly fast. Within the lifetime of the apostles, it had been preached in North Africa, in India and in great parts of Southern Europe. We moan these days about the Church’s diminishing resources. We must remember, therefore, where our faith originates. A few days ago, we read, in the Divine Office, this Isaian exhortation: ‘Look to the rock from which you were cut, to the quarry from which we you were hewn.’ The manger is a better example of normative Christian reality than our great medieval cathedrals. Our Saviour chose poverty of means. From within that poverty, he conquered the world. Should we then complain about failing resources?

We shall never sufficiently wonder at the fact that God, almighty creator of heaven and earth, chose to become poor and vulnerable. The image of the manger has been used, in recent years, to alert us to the Lord’s solidarity with those who suffer. This is one aspect of the mystery of Christmas, but not the only one. God became man, not just to comfort us, but to elevate us. We who easily live imprisoned in the horizontal plane, absorbed by what goes on around us and within us, may lift up our heads, then our hearts. Heaven opens.

Once we get the hang of this, the earth looks different, it will never be the same. We are graced with mysterious lightness even when we carry heavy loads.

‘God’s grace has been revealed’, writes St Paul, ‘and has made salvation possible for the whole human race.’ Once upon a time, ‘salvation’ was a straightforward business in this country. Within the framework of a long-reigning religious culture, you could ask a man or woman, ‘Have you been saved?’, and you’d receive a clear answer. It would be either yes or no. It is no bad thing, perhaps, that a few nuances gradually entered this discourse. However, the pendulum has swung far in the opposite direction. These days, ‘salvation’ seems like a term from a bygone age, even for believers. We’ve got so used to being needless that we don’t sit around waiting for someone to save us: if our own strength runs out, we can always lean on the welfare state – or on the internet, which delivers cardboard-wrapped solutions to our problems to our door as long as our credit card is in balance.

Perhaps it is by the providence of God that fragility spreads throughout the world. There is something trollish about being ‘enough to oneself’, in the words of Ibsen’s play Peer Gynt. We have been enough to ourselves for far too long – and have ended up troll-like. Sanitary, ecological, and political crises create insecurity, of course. But what chance does God stand of accessing our consciousness as long as we’re convinced we can save ourselves? When Ahaz, king of Judah, received the sign of Emmanuel, he was in a state of fear so all-embracing that his heart shook ‘the way the trees of the wood shake before the wind’. That’s how Isaiah puts it. Fear can be a harbinger of consolation, if we let ourselves be consoled.

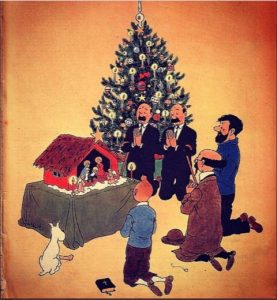

In this most sacred night we remember that God illumines us; indeed, that he enables us, by grace, to become light. The Babe we worship is the origin and principle of light. My Christmas wish to myself and to you is a new awareness of who our Lord Jesus Christ really is. If the Church of our times is in the throes of great tribulations, it is principally, I’d say, because our faith has become superficial and banal. We’ve turned it into a product of welfare, expecting it to serve our purposes. In fact, the purpose of faith is the opposite. It is to enable us to serve God humbly, reverently and generously, and thereby to find beatitude and true freedom. ‘Today a Saviour has been born to you. He is Christ the Lord.’ An excellent prayer to pray at Christmas, and all year round, is this: ‘Lord, teach me to know you as the world’s Saviour and as my own.’ Only when we have reached the degree of insight that permits us to exclaim, on our knees before the Christmas crib, ‘My Lord and my God’, will we realise what it means to live by faith.

Then God’s glory will enlighten the night even here in the far north, where nocturnal darkness is compact and long-lasting. To each and every one of you: A blessed Christmas! May Christ renew our lives!