Words on the Word

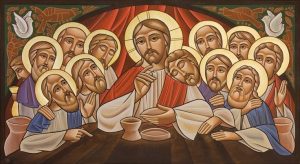

Corpus Christi

Genesis 14:18-20: Melchizedek king of Salem brought bread and wine.

1 Corinthians 11:23-26: This is what I received from the Lord.

Luke 9:11b-17: You give them something to eat.

In our second reading we heard Paul say, ‘Brothers, this is what I received from the Lord, and in turn passed on to you: that on the same night that he was betrayed, the Lord Jesus took some bread’, etc. Literally speaking, the statement is false. 1 Corinthians was written in the early 50s. Paul had then been a Christian for 15-odd years. His conversion had taken place well after Christ’s crucifixion and death. Paul, unlike the Twelve, was not present at the Last Supper. He did not receive the sacrament — the medicine of immortality — from the Lord’s hands; he did not hear Jesus’s voice declare: ‘Do this in memory of me’. So what is he talking about?

In his letter to the Galatians, written before the one to the Corinthians, Paul explains how he came to faith. He presents his competence in the field of Pharisaical theology, his violent zeal for the religion of his fathers. When he first encountered the Christian phenomenon, he considered it blasphemous. He wished to annihilate it. He ‘raged’, Luke tells us, ‘against the Lord’s disciples’, leading them, women and men, ‘in chains to Jerusalem’ (Acts 9:1-2), there to be tried before competent authority.

The something happened. God, says Paul, ‘was pleased to reveal his Son to me’ (Gal 1:15-16).

In Acts we are told how this came about. Paul was bound for Damascus. He was chasing ‘the church of God‘ (Gal 1:13). While travelling he saw light from heaven. The light surrounded him. He recognised it as light not of this world — like the light seen by Moses at the burning bush, by Isaiah in the temple, by the disciples on Mount Tabor. From within the light a voice issued: ‘Saul, Saul, why are you persecuting me?’

Struck to the ground, Paul was blinded. The parameters by which, so far, he had staked out his course were no more. He had to surround himself into others’ hands. ‘So they took him by the hand and led him to Damascus’. He remained there for three days, the same amount of time the Lord lay lifeless in his tomb. Paul languished without sight, without eating or drinking, as if he were dead, until Ananias, called by God, came to him proclaiming: ‘The Lord Jesus […] has sent me that you may regain your sight and be filled with the Holy Spirit.’ Scales fell from Paul’s eyes. He stood up, was baptised, ate and drank, then started preaching Christ in the synagogues saying, ‘He is the Son of God’ (Acts 9:10-20).

In retrospect Paul was keen to stress that the Gospel he had received was no human confection: ‘Jesus Christ’, he explained, ‘revealed himself to me’ (Gal 1:11f.). True enough, but Christ encountered Paul through the Church. It was the Church Paul pursued; yet the Lord asked, ‘Why are you persecuting me?’ It was through the Church that he was healed of blindness. In the Church it was given him to share in the Body and Blood of Christ, the mysteries we have heard him say he received ‘from the Lord’. In all this we touch the existential background for Paul’s mature teaching about the Church as the Body of Christ (e.g. Ephesians 1:22f.).

Th Church is the real presence hic et nunc of God’s Son’s personal, healing, freeing being and action. There is no contradiction, in faith, between Christ and the Church. On the contrary: the Church, which is a sacrament (Lumen Gentium, 1) communicates a union with Christ which, if we believers allow it to take place, transforms our being. In so far as we live in the Church, we can say with Paul, ‘It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me’ (Gal 2:20) — a wonderful gift, though one that presupposes that we empty ourselves the way Christ emptied himself (Phil 2:8), that we walk as he walked (1 Jn 2:6).

The solemnity we celebrate today is not about a magic talisman in an ornamental cupboard. I do not thereby intend any disrespect to the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar. I simply wish to point towards a temptation we must resist, namely the temptation to consider Christ’s Body and Blood as stuff for individual consumption, be it consumption of a sublime order. In this area, great watchfulness is called for. We are so deeply marked by static materialism that we struggle to discern and recognise dynamic spiritual reality.

As so often, the liturgy offers us a helping hand. Our collect today refers to the Eucharist as passionis memoria, that is ‘a memorial of [Christ’s] Passion’. The sacrament renders a divine, saving action palpably present. This action presupposes the communion of the Church, in which Christ is present, through which he exercises agency. The Lord has chosen to convey sacramental grace ecclesially. No one can administer a sacrament to himself, be he the most exalted hierarch.

Christ’s Body and Blood touch us viscerally, yet their mystery must not be boiled down to a private devotion. It isn’t as an object of meditation that Christ’s concedes his sacramental presence. Let us remember his words to Mary Magdalene in the garden: ‘Do no hold me, cling to me [as if I were your possession]’ (Jn 20:17). Christ is subject per definition. We are indirect objects of his action. Christ’s Body and Blood would renew our nature in Christ in such a way that our lives become sacraments of Christ. Thus, and only thus, can we heed his exacting command in today’s Gospel, given in the face of that needy humanity for which Jesus gave his life: ‘You give them something to eat.’ The precondition for doing that without yielding to intolerable presumption is by living on him, through him, in him. Amen.

‘Do this in memory of me.’