Words on the Word

Day of Consecrated Life

Each year the religious of the diocese gather in the cathedral on the Feast of the Presentation of the Lord. This year we couldn’t on account of Covid-related restrictions, so the encounter was held on 21 March instead.

2 Kings 5:1-15a: Could I not bathe in the rivers of Damascus?

Luke 4:24-30: No prophet is ever accepted in his own country.

‘There were many pepers in Israel in the days of the Prophet Elijah’, says our Lord, ‘but none of these was cured, except the Syrian, Naaman.’ In order to pick up the undertone of this lapidary statement, we must consider the story of Naaman in a little detail.

Naaman served in the army of the king of Aram, in Mesopotamia. Israel’s claim to enjoy a privileged relation with God was made known to him through an Israelite slave. Normally it will, one supposes, have been beneath his dignity to seek servants’ advice (he was a captain); however, he was desperate. Leprosy was slowly but surely consuming him.

What he was given to hear about the prophet of the Lord gave him hope. When we’re really poorly, we seek remedies anywhere. Cures abroad have a special attraction. Naaman set off, then, with many precious things in his luggage. He wished to make it clear that he was ready to pay for treatment. He was conscious of his social position.

Like most patients, he was sure of being subject to a singular complaint. He expected to give the prophet a thorough account; then to be met with recognition and a tailor-made, sophisticated programme of treatment. When we go and see the doctor, it is, not least, to be seen and heard, to sense that someone cares and takes us seriously, even if we have to foot the bill for such care.

It isn’t strange that Naaman was upset when Elisha didn’t even come out to greet him. He merely sent a message out with his secretary: ‘The cure you need, dear Naaman, lies right in front of your feet, freely available. Your condition is perfectly ordinary.’

Elisha takes neither his temperature nor his blood pressure. Nor does he bother to give the ailment a multi-syllabled label. Naaman is offended: ‘Doesn’t this quack realise how extraordinary I am?’

It takes the pragmatism of his staff to prevent him from going straight back to Aram. They say: ‘Since we’ve taken the trip, why not test the waters?’ We know what happens. Naaman’s amazed jubilation resounds centuries later, when our Lord proclaims his blessed Gospel in Nazareth, not far away from the Seminarian territories of Elisha.

What has this story to say to you and me, gathered for a day of consecrated life? Rather a lot. We also live with sickness. We are sadly conscious of the scab that afflicts the body of the Church. Our communities get older and less numerous. Solid new vocations are rare. We, too, like Naaman, seek remedies apt to restore energy and health. We tend, like him, to look towards that which is novel and a little exotic. We experiment with processes that carry complicated names, convinced that what we’re living through is unlike all else that the Church and humanity have ever known before.

What if we simply followed the prophet’s prescription, ‘Go down and bathe seven times in the Jordan’? In other words, what if we made full used of the resources that, by God’s providence, we already possess, trustful that our covenant still carries abiding strength? Specifically this involves rediscovering, effectively and enthusiastically, our Rule of Life, the vows we’ve made (to which we’ve pledged to be faithful until death), not least the evangelical counsels: obedience, poverty, and chastity. This is where we shall find the living, healing water we need, a source of blessing and of nearness to Christ here and now.

We are invited to rekindle our first love, to say Yes to the promises of Jesus and to his commandments; to take resolute leave of compromises that over time, as well we know, can accumulate and extinguish our fervour.

Perhaps our current malaise isn’t, in fact, something specifically post-postmodern. Perhaps it points to an ancient, in itself quite banal motif: a need for radical conversion and new rootedness in heartfelt devotion. In the Prayer over the Gifts this day, we pray: ‘May what we offer you, O Lord, in token of our service, be transformed by you into the sacrament of salvation.’ What we offer is not just bread and wine; we likewise offer afresh our consecrated lives. Let’s surrender them freely, unconditionally, into the Lord’s hands. He is well able to work great deeds this very day, even with our modest means.

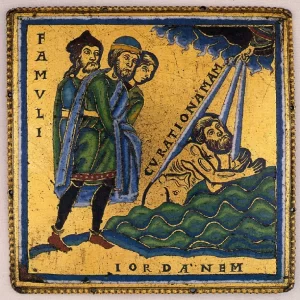

Plaque from an altar retable showing the cleansing of Naaman, made in the Meuse Valley, ca. 1150–60. Gilt bronze and champlevé enamel, 10 × 10 cm. British Museum, London.