Words on the Word

Good Friday 2025

Isaiah 52.13-53.12: The crowds were appalled on seeing him.

Hebrews 4.14-5.9: He offered up prayer and entreaty.

John 18.1-19.42: Woman, there is your son.

‘The crowds’, says Isaiah in his mystic prophecy, ‘were appalled on seeing him’. We do not know whom in particular Isaiah had in mind; but the reality he describes corresponds so perfectly to Christ on the cross that his millennial words give us goosebumps.

The prophet draws a picture of justice spurned, tenderness trodden under foot. We see philanthropy spat at, human dignity denied. That such things can, and do, happen, we know well; but we prefer not to think about it. We avert our gaze, zap to a different channel, glad to be distracted.

Today, though, distraction is no option. We stand face to face with the cross, with Christ’s wounds. In faith we acknowledge what Isaiah intuited: ‘he was pierced through for our faults, crushed for our sins’. We are part of the picture. The crucifixion cannot be turned into an abstraction à la Salvador Dalí. The cross is sovereignly palpable. It touches us; and today we touch it. One by one we kneel before it to kiss it, each of us carrying his or her own burden, often known to no one but ourselves. We are excused, today, from having to pretend that all is well. We bear our load, at the same time know we are carried. ‘By his wounds we are healed’. Yes, it is accomplished.

‘Behold the man!’, said Pilate, the politician. True enough, the crucified shows us what we, you and I, are capable of doing to each other: ‘The evil tidings of what man’s presumption made of man’, wrote Primo Levi. He had been a prisoner in Auschwitz. He knew what he was talking about. This is a perspective we must not lose out of sight, for it is repeated incessantly; it is unfolding now. The cross confronts us with our penchant for cruelty, indifference, hatred. It invites us to weep over our hardened hearts, to cry Kyrie eleison!

Though we choke on our exclamation when we realise: he, our Kyrios, is nailed before our eyes. Our misdeed is not perpetrated against man alone; it is God we have sought to tear ‘away from the land of the living’. We have wanted to finish him off. The cry we just heard in the Passion — ‘Away with him! Away with him! Crucify him!’ — stirs our conscience. For have I not, albeit more subtly, in secret, thought likewise? Have I not sometimes wished to cancel God in order, at least for a while, to be free of his demands and my betrayals? When I hear him say, ‘what I have done for you, you must do for one another’, do I not often wilfully turn a deaf ear?

To fix our gaze on the crucified is to recognise these three contrasting, apparently contradictory facts: my weakness, my rebellion, and God’s patience. It is good for a person, and for a people, to be measured against such a standard. Considered responsibly it can lead us to humility, penitence, and loving fear of God.

If we look back over a thousand years of Christian civilisation here in our country, and in Europe, we see it has flourished best, and brought forth its finest fruits, when the cross has been kept in attention thus. We ascertain from the accomplishments of Christians — Fra Angelico and Dante, Undset and Bruckner, Mother Teresa and Gaudí — that the cross is, as the liturgy acclaims by way of imagery, the Tree of Life. ‘For behold’, we sing on this day, in what may be the Church year’s boldest assertion, ‘by the cross joy entered the world.’ We do not glorify the cross’s pain and humiliation. No, we shed tears over them. But we ascertain that God can effect consolation through pain, life through death. Even sin itself, our absurd mutiny against beatitude, can be yoked into service for the sake of the good.

The cross displays compassion as a carrying force in relations both human and divine. God bears our burden on our behalf. That way he annihilates death. He short-circuits the current of violence by freely letting himself become ‘a pure victim, a holy victim, a spotless victim’, as we pray in the Roman Canon. He bids us live and die likewise. This commandment is explicit in the teaching Jesus proclaimed while he walked about doing good: ‘Whoever would be my disciple must take up his cross and follow me’ (Mt 16.24). It is symbolically manifest on Calvary when Mary, the Mother of the Lord, in whom the Church recognises an image of herself, stands at the foot of the cross. What she must have suffered there only mothers among us can know, humanly speaking. What her compassion meant in principle we learn from theology. It is underneath the cross, in wholehearted incorporation into Christ’s saving work, that the mission of the Church is enacted. When the Church blesses and consecrates, it is with the sign of the cross. Should she try to work otherwise, she would cut herself off from the tree of life and wither.

This is a message the world has always struggled to understand. The cross, as a pledge of transformative compassion, was scandalous already in apostolic times: that much is clear from St Paul’s letters. Nietzsche despised the cross as a denial of his notion of the Übermensch: we know what that led to. Recently a tradesman who these days has much to say about a lot, and has sophisticated broadcasting equipment, declared that empathy is the West’s Achilles heel which ought to be replaced by a digitally engendered prosthesis in steel. It cannot be stated too clearly that Christians must distance themselves from such drivel.

The world rejoiced by the cross is not a world of deals in which people, and peoples, are tradable; it is a world that inaugurates a new earth where a wounded God shall be all in all, and our nature will be renewed by grace. Sing, then, tongues of Christians of the triumph of the cross and of its price! Do not be brought off course by siren songs. Christ, our high priest, offers us the bread of life and the wine of gladness at the altar of the cross. Shall we then instead opt for a nourishment of trollish pebbles? No way. Amen.

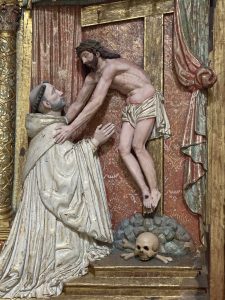

Relief from the Cistercian abbey of Cardeña, showing St Bernard’s vision of the crucifixion.