Words on the Word

Vigil of St Olav

A German version of this text is available here.

Joshua 3:14-4:8: What stones are these?

Colossians 1:9-17: he si the image of the invisible God.

Matthew 5:13-20: When salt has lost its saltiness, it is good for nothing.

Our first reading tells of something strange that took place when Israel, after forty years in the desert, reached the promised land. Moses, who had led the people out of Egypt, was dead. He had stood solitary on Mount Nebo, on the peak of Pisgah, and looked into the land of which God swore to Abraham. The Lord said: ‘I will give it to your descendants, but you shall not cross over there.’ Moses’s commission reached to this point, no further. He died abroad, in Moab, and was buried there, no one knows where.

It pertained to another to lead Israel into the fulfilment of the promise.

Joshua had been Moses’s assistant for years. He was filled with the spirit of wisdom. ‘Moses had laid his hands on him’ and consecrated him for the task. The Lord said to Joshua: ‘Only be strong and very courageous, being careful to act in accordance with all the law that my servant Moses commanded you; do not turn from it to the right hand or the left, so that you may prosper wherever you go.’

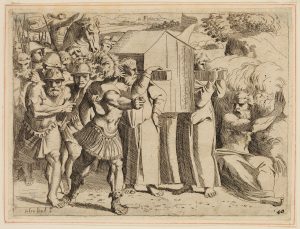

This exhortation is enacted in the text we’ve read. The Law, symbolised by the Ark, divides the Jordan. The frontier between exile and homecoming is opened. We see that the land and the Law belong together. It was God’s purpose that the people there should live after it. The history of Israel illustrates this connection again and again. Whenever Abraham’s children forget the call to live by God’s Law, whenever they fancy that the land is theirs and that they can live in it as they please, by their own lights, the Lord withdraws his benediction; indeed, he tears down what they have built up. Even in everyday, pragmatic matters there’s usually a payback if we mistake means for ends. Where a divine mission is at stake, the confusion is fatal.

The Israelites were no seafaring people. Unlike Norwegians or Greeks, they were not susceptible to the charm of salt-sea air. In the Bible water represents chaos. Water is the element of Leviathan.

Waters parted to let Israel our of Egypt. Waters parted again to admit Israel to the land that represented their freedom, freedom not just to survive but to know supernatural, eternal life, in pursuit of the Law. Joshua knew that a memorial was called for to keep the call alive in collective remembrance. That is why he prescribed the procedure we have read about. Twelve stones, one per tribe, were lifted out of the riverbed and rigged to form a cairn on the riverbank. Through the grace of the Law Israel had come home. This they had to remember. The Gilgal cairn was designed to provoke remembrance. It will hardly have looked pretty. It served no practical purpose. New generations were bound to ask, ‘What stones are these?’ In this way the account of redemption would be passed on. Stones would bear witness to life.

We find ourselves in a place that is a Norwegian Gilgal. Stiklestad stands for the Christianisation of our country. Naturally other factors, too, played a part then, in 1030. People’s intentions are complex; faith has a political dimension that constantly requires purification. Still, it is beyond doubt that Olav’s wish was to conquer the land, not for himself, but for Christ. His army proceeded under the banner of the cross. The cross indicated the New Law, just as the Ark had indicated the old. The old and the new forms a whole. In Hebrew, ‘Joshua’ and ‘Jesus’ are one and the same name: The new Jehoshua fulfils that which the old had begun. ‘I have not come’, we have heard Christ say, ‘to abolish, but to fulfil’. To belong to Christ is to follow his Law. It transcends historical conditioning and cannot be relativised. The Word who became flesh was from the beginning and embodies the finality of history. Christ is Alpha and Omega. In him and for him we were made. Human accomplishments, notions, and cultural norms come and go — they are like the flowers of the field. Christ’s word, meanwhile, the new Law, remains. It will never be obsolete.

A word like ‘law’ makes us cringe these days. We think of it in terms of rules and duties. We don’t like that kind of thing. We don’t want others to tell us how we are to live; we wish to create our own reality. But do we, in fact, know who we are, what we have the potential to become? Around us, and perhaps within us also, we see signs of confusion. Remember, then: the Law Christ gives is a dynamically orienting law. It shows us how we are to live in order to reach our full measure, in order to step into a landscape beyond our earthly horizon. When Joshua led Israel through Jordan, he ordered that the Ark, that is the Law, should go first. The people were to follow two thousand cubits behind. ‘Follow it’, said Joshua, ‘so that you may know the way you should go, for you have not passed this way before.’ To live by faith is to venture into newness. Do we wish to follow Jesus into a divine reality that necessarily transcends our expectation? Or do we stay stuck in time, within the limitation of what we think of as ours, to be buried in Moab?

The memory of Israel’s call and the gift it contained was kept alive in Gilgal for a while. Then it perished. Already under the early prophets, Gilgal became the centre of a decadent cult. ‘Come to Gilgal and multiply transgression’ cried Amos, full of disdain (4:4). How hard it is to live, over time, with hearts and minds raised heavenward when so much here on earth attracts and distracts us!

How can we ensure that the cause of Jesus Christ, the cause for which Olav died, remains alive here at Stiklestad? We must be conscious of what really happened here. What is this ‘really’ supposed to mean? That we believers must recall and recount Olav’s sacrifice in the light of faith; that we must remain conscious of it as something vibrant and life-giving without letting it be frittered away.

Is this to happen, we must each of us fight our daily Battle of Stiklestad within. It amounts to proceeding trustfully under the banner of the Cross, certain that, as Paul writes, love without deceit presupposes the word of truth — a truth, he stressed, that must be spoken in love; if it is uttered angrily, it almost invariably becomes counterproductive. Christ revealed himself as truth. We receive him, his words, his commandments, as truth, with thanksgiving. The truth sets us free.

To let history, our times, ourselves be illumined by Christ: this is the task to which Stiklestad summons us. Society’s tendency, it must be said, goes in the opposite direction: Christ is overshadowed by our view of ourselves, our times and history. A minimalistic, smartly fashionable bushel is placed over eternity’s light, which is gradually quenched, then eventually extinguished, letting out a sad little sigh no one notices. Only when darkness surrounds us do we realise what we have lost. Let us, then, brothers and sisters, be courageous and strong, not in our own strength, but in that of Christ Jesus. If we do not turn away from him, either to the right or to the left, we can tread wisely through the waters into the kingdom of his grace.

The sequence for the feast begins with the words, Lux illuxit laetabunda: In Christ, through Olav, a gladsome light spread over our land as a source of light. Let us nurture it faithfully in life and death. Amen.