Words on the Word

Palm Sunday

Luke 19:28-40: If these were silent, the very stones would cry out.

Isaiah 50:4-7: The Lord has opened my ear.

Philippians 2:6-11: Christ Jesus emptied himself.

Holy Week is underpinned by Jesus’s assurance that everything that happens has to happen. He has predicted it in detail: ‘everything that is written of the Son of man by the prophets will be accomplished. For he will be delivered to the Gentiles, and will be mocked and shamefully treated and spat upon; they will scourge him and kill him’ (Lk 18:31-2). This is the purpose for which Christ enters Jerusalem.

The imperative that governs the life and death of Jesus is no secret. It is revealed from the time of his birth, when Mary is told that a sword will pierce her heart. The Gospel of Luke, from which are readings are taken this year, shows us Jesus’s life as a clearly defined, linear, free ascent towards the Cross. The Son of God becomes man in order to be sacrificed. The sacrifice must be brought in Jerusalem.

Jerusalem is not reducible to a theological metaphor, an image of definitive oblation; first and foremost, it’s a spot on the map. When a group of well-intentioned Pharisees (there were, let’s not forget, some of those as well) warned Jesus against his enemies and advised he go underground, he says with paradoxical enthusiasm, even a kind of joy: ‘I must go on my way today and tomorrow and the day following; for it cannot be that a prophet should perish away from Jerusalem’ (Lk 13:33). He is like an athlete facing the final lap, his sight set on the crown of victory.

Only his crown is made of thorns. The victory is won by his destruction.

How are we to understand this? And how are we to imitate Jesus’s example. After all, he has said: ‘If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow me’ (Lk 9:23). It’s a commandment sharply defined. It’s impossible to wrap it up in cotton wool.

In the Bible, Jerusalem stands for the fulfilment of God’s promise. In Jerusalem the covenant is given its most sublime expression. The city is, biblically speaking, inseparable from the temple in which God’s grace is efficaciously at work. The Psalms are full of the praise of Jerusalem. Some of them were sung by pilgrims making their way up to Zion for the feasts. Some are laments from exile: ‘If I forget you, Jerusalem, let my right hand wither!’ (Ps 137:5). We grasp the city’s importance and Israel’s passion for it.

Ezekiel calls Jerusalem ‘the navel of the earth’ (38:12), the focus of creation. On Palm Sunday something phenomenal takes place: The Word made flesh, by which all things were made, steps into this magnetic field. He, the eternal high priest, approaches the Ark of the Covenant, the altar of propitiation. Hardly anyone in the palm-waving crowd will have been conscious, there and then, of all the factors that were playing in symphony — it took the Church decades to work them out; yet we sense an intuitive understanding that something momentous was about to take place. The Lord who, till now, has preferred to work in secret, speaks clearly. When someone asks him to get his disciples to shut up, he retorts: ‘If these were silent, the very stones would cry out’. It is the universe as such that is vibrating. Not for nothing do we hear that Jerusalem shook (Mt 21:10). Creation’s deep groan, mostly uttered in silence, in the hope of freedom from transience’s enthralment (Rm 8:22) was shouted out aloud by the Hebrews’ children.

Jesus strides peacefully forth through this air of ecstatic expectation. His eyes are fixed, not on the signs of honour he receives, but on the cross that rises on Mount Calvary, just outside the city. An accomplishment takes place, by all means; but he also signals the upbeat to something quite new. The new presupposes the coming to an end of what is old. Between the two Gospels the Church gives us today (first the account of the entry into the city, then the passion narrative), Luke reports a confidential discussion that takes place between the Lord and his nearest disciples. The disciples are enchanted by Jerusalem: by everything that city has stood for in the past, by its promises now, by its solidity and glory. All these things together add up to, surely, a pledge of the Lord’s special favour and protection? Jesus answers: ‘As for these things which you see, the days will come when there shall not be left here one stone upon another that will not be thrown down’ (21:6). Again this mysterious necessity, pointing towards destruction.

Is Christianity, then, a kind of destructive fatalism? No! The Lord just reminds us that death (our own, but also the death of cultures and of civilisations) is intrinsic to life and that we, to see the sense of it all, must look beyond death. He reminds us that history progresses towards a goal which is of eternity. Ever again we must lift up our hearts in order to be able to raise our eyes.

We are in this world, called to make it lovely and fruitful, but we are not of the world. To see this is comfort, but costly comfort. We are bidden to let go of all that, now, gives us security. We must learn to seek our security in God. Only with him is it lasting. He will lead us towards the fullness of the promise by which, and for which, the world was made.

Freedom from the slavery of transience is won when that which is transient falls. Jesus speaks of violent, frightening ‘signs’: ‘Nation will rise against nation, kingdom against kingdom; there will be great earthquakes, and in various places famines and pestilences; and there will be terrors’ (Lk 21:10-11). There is no shortage of such signs in our world. We often read them as meaningless, and are thus tempted to despair. Jesus meanwhile exhorts us: ‘look up and raise your heads’. Our redemption, he says, is at hand.

Today, in Jerusalem, Christ enters this world’s this-worldly hope. He confirms that hope — what has to happen happens — then raises it to a new level, where it loses its earthly foothold and must learn to soar. This detachment is one we must all live through. We must learn that life reaches fullness through death; that death at every level has lost its sting and is no longer something to be feared. The process will be configured uniquely and personally for each of us. Its structure, however, remains the same. It is displayed before our eyes this week, in the Pasch of Jesus, ‘the pioneer and perfecter of our faith’ (Heb 12:2). He shows us how we are to believe. Let us follow him faithfully, then, and attentively, that thus we may learn anew, in trust, how truly to live.

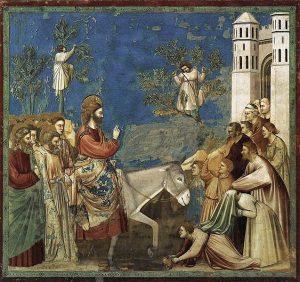

Giotto’s account of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem, from the Scrovegni chapel.