Words on the Word

Palm Sunday

Mt 21:1-11: You will find a donkey.

Is 51:4-7: The Lord opened my ear.

Phil 2:6-11: He emptied himself.

Pam Sunday is marked by strong sensual impressions. We read of people in a state of feverish expectation thronging the narrow alleys of Jerusalem. We can imagine the noise and commotion, the smells. The air must have vibrated with tension. The procession had a political dimension; at any rate it lent itself to being politically exploited. Anything could happen. For us, too, this is a day marked by confusion. We perform rites that recur only once a year. We fall over one another, unsure where to turn, what to do, what is expected of us. We step out into the late winter waving branches and singing, a public display of faith that makes us Norwegians blush, accustomed as we are to religion being a private matter.

There is a lot, then, to distract us. We must rise above it. In the middle of the chaos a calm figure advances, seated on a donkey. To him we must raise our gaze. He is, we have sung, the scion of David praised by angelic hosts, the fulfilment of Israel’s hope. He is our King and our Redeemer. But how do we see him in fact?

To let us contemplate the face of Jesus, the Church, our Mother, gives us a reading from the prophecy of Isaiah. It is a wonderful text. It describes how the Lord awakens his Chosen to his mission. He gives him the tongue of a disciple that he might ‘reply to the wearied’. He opens his ears that he might ‘listen like a disciple’. For years the Lord Jesus has walked among men in this way. He has heard, not only their cries, but their sighs and the secret longing of their hearts. Tirelessly he has comforted the weary, restored health to the sick, even raised the dead.

Has man let himself be comforted? For a while, yes. But not for long. There’s a hidden violence glowing within us. We feel humiliated by benevolence; we wish to strike off another’s extended hand. We have a weird urge to sabotage goodness, even if thereby we ruin our own happiness. The disciple of whom Isaiah sings knows what lies ahead. His strengthening words will be repaid to him with blows, insults, and spittle. He will be maltreated, but will not be put to shame.

Isaiah wrote up this text some 700 years before Palm Sunday. What does it mean that it is given us to read as an account of what Jesus goes through? Is it a case of fortuitous coincidence, the way we might find our experience expressed in texts that have nothing to do with ourselves, a poem by Dickinson or a short story by Chekhov? No, something more essential is at stake. The Man on the donkey is not a mere individual, a lone heroic figure. He is the Image of the invisible God (Col 1.15), the image in which we were made. He structures the universe and gives it meaning. He is the one, eternal Word which Scripture’s multiple words as a whole express. By his Spirit he has, as we say in the creed, ‘spoken through the prophets’. Mystically, it is Christ who speaks in Isaiah and through his experience. What we celebrate in Holy Week is more than grand historical drama. It is the distillation of the human condition. During these days we are handed the key to unlock the riddle of existence, including our own existence.

This is what I want you to take to heart. When we contemplate Christ in his Paschal mystery, we also see ourselves. Our humiliation and grief are contained in his oblation. Our sin is the burden he carries, unseen though symbolically present in the crown of thorns. Also the good that, by grace, lives in us, our hopes and best aspirations, are carried by him through annihilation into eternal life. Christ is the pattern by which we have come into being. He indicates the way we must follow. Today’s collect calls him an exemplar from whom we are to learn. What do we learn? That the distance from cries of Hosanna to ‘Crucify him!’ is short, a matter of a few days. We learn that goodness, here in our wounded world, is up against fierce resistance, but nonetheless conquers in the long term. The hymn to Christ, our King which we sang on entering the church concludes with the words: ‘Good King, clement King, all good things are pleasing to you.’ By committing ourselves to doing good despite all, by carrying out and sharing the good in Jesus’s name, we bring him joy in his humiliation for our sake.

Remember: when we see Jesus proceed firmly towards Calvary we find ourselves at once in the past and in the present. In this Mass, as in every Mass, we are gathered at the foot of the Cross. That is something we must take very seriously.

When Jesus strode forth into the holy city, the centre of the earth, where he knew he would be denied and tormented, the people spread their cloaks before him on the road. No doubt their action was sincere. There and then they meant what they said when they cried, ‘Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord’. We, who read each part of the story in the light of the whole, know how the climate will have changed by Good Friday. That insight lets us examine ourselves and our motivation. Are we prepared to remain by Jesus’s side even in his ignominy? In a moment we will sing, ‘Blessed is he who comes’ to prepare the presence of the Lord here, in our midst, on this alter. May that be our heartfelt, unshakeable confession in time and eternity. Let us spread before his feet not only our cloaks, but our lives. Amen.

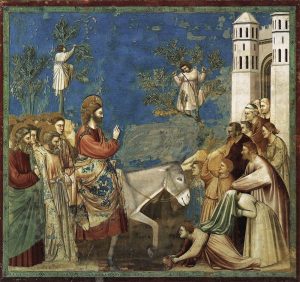

Giotto’s representation of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem. Wikimedia Commons.