Words on the Word

Pentecost Vigil

Genesis 11.1-9: Let us build a town and a tower reaching heaven.

Romand 8:22-27: We groan inwardly.

John 7:37-39: If any man is thirsty, let him come to me and drink!

We stand on the threshold of Pentecost, the culmination of Eastertide. The Church expectantly robes herself in red, the colour of testimony. But what exactly are we waiting for? The word ‘Pentecost’ may carry a somewhat sour undertone for us Catholics of today, marked by a particular ecclesial context.

In the 60s and 70s it was all the rage, among prelates and people alike, to speak of a ‘new Pentecost’. It seemed natural in those days, when so many dreamt, at various levels, of a world working on new terms. Promises were given of a peerless effusion of Spirit, of charismatic renewal, of societal transformation. By all means: much that was good took place. But what fruits do we see now, half a century down the line?

Let’s beware of superficial judgements. We have every reason to admire God’s work. That said, expectations of renewed Christendom have not been met. Not only has dechristianisation proceeded at phenomenal speed; many ‘charismatic’ projects and persons have turned out untrustworthy, some downright destructive. Therefore we are sceptical, now, when people invoke the renewing power of the Spirit.

It is as if the very concept of renewal were in need of repristination.

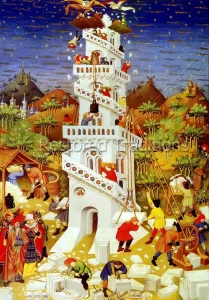

For this Vigil Mass the Church lets us read the story of the tower of Babel. We can see why. The confusion of languages and the fragmentation of humanity point forward towards what the Spirit wrought on the fiftieth day after the Resurrection, when all the peoples of the earth, gathered in Jerusalem, heard the Gospel proclaimed in their own tongue. The Church, born at Pentecost, made good that which was ruined at Babel.

For this Vigil Mass the Church lets us read the story of the tower of Babel. We can see why. The confusion of languages and the fragmentation of humanity point forward towards what the Spirit wrought on the fiftieth day after the Resurrection, when all the peoples of the earth, gathered in Jerusalem, heard the Gospel proclaimed in their own tongue. The Church, born at Pentecost, made good that which was ruined at Babel.

Let’s not, however, pass over this narrative too quickly.

What does Babel’s tower stand for? It was intended as the focal point of an all-embracing polity. The top of the tower would reach to the heavens and bring heaven, rethought in the image of man, down to earth. The architects usurped the prerogatives of God, intoxicated by their own ambition, by the thought of their omnipotence. The image speaks powerfully to, and about, our own times. God saw that such a project could not end well. ‘Nothing will now’, he said, ‘be too hard for them to do.’ So he sabotaged the project, for philanthropy’s sake.

For a paradise thought out by humans sooner or later turns out to be hell. We have seen that time and again.

Yet the mindset of Babel retains its charm. We justify it as well as we can. If our notions of Pentecost are superficial we may turn into tower-constructors ourselves. If we assume that the Spirit will manifest itself spectacularly, in earth-shattering events and powerful emotions, through towering, eloquent, charismatic agents; well, then we may come to think that the ‘age of the Spirit’ represents a new reality marked by ecstasy, fire, transformative energy. Such a maximalist reading of Pentecost flatters our Babelic penchant, our vanity. It lets us work out enterprises of self-glorification as if we possessed here and now, under our own steam, ability to create a new heaven, a new earth, as if the work of redemption were already past. We think: ‘We who have left sin behind and are free can abandon ourselves to the Spirit’s charisma!’ Nothing then stands in the way of sentimental despotism.

Paul ascertained this, not least in his work at Corinth; we ascertain it in our own settings.

If we consider the damage the Church has suffered and caused over the past decades, is it not often tied up with a perverted understanding of Pentecost, of the Spirit? Has not a caricatured ‘holy spirit’ at times become an idol? The question merits reflection.

The Church’s authentic teaching provides clear parameters, thank God. Today’s collect [the one set for Saturday in the seventh week of Easter] gives a good example:

Grant, almighty God, that we who have kept to the end the Paschal feasts may, by your gift, hold on to them by our life and manners.

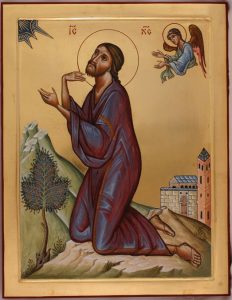

Paul had received the Holy Spirit: there’s no doubt about that. Still he exclaimed to the Corinthians: ‘I have not wanted to know anything among you except Jesus Christ and him crucified.’ To the Romans he wrote: ‘We who possess the first-fruits of the Spirit groan inwardly as we wait for the redemption of our bodies.’ Pentecost stands at once for an already and a not yet. The Holy Spirit is inseparable from the sacrifice of Christ on the Cross. The Cross continues its work until the end of time. Any so-called charisma that works on terms different from those Christ displayed in his self-outpouring, that do not resemble him who came not to be served but to serve, is not from the Holy Spirit.

inseparable from the sacrifice of Christ on the Cross. The Cross continues its work until the end of time. Any so-called charisma that works on terms different from those Christ displayed in his self-outpouring, that do not resemble him who came not to be served but to serve, is not from the Holy Spirit.

I say this not to give Pentecost a sorrowful or gloomy aspect. Not at all! I simply stress that we cannot pretend we have somehow passed beyond Christ’s Paschal oblation, which is still working itself out. We must be on our guard against illusions and against our personal pride, which inspires us to want to manage on our own; instead we are called to live by trust, on grace, which is an infinitely sweeter form of existence. Let him who thirsts come to Jesus to drink; let him drink of his chalice, no other’s. Wine from elsewhere may tickle our palate for a moment, but will intoxicate without bringing either freedom or power – or joy or beauty or purity.

May the Spirit grant us a thirst for truth and grant us ability to distinguish between what is true and what is fake, for our own good and for the world’s salvation.

Amen.