Words on the Word

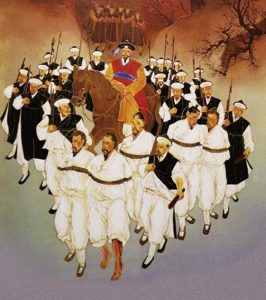

The Korean Martyrs

Ezra 1:1-6: The lord roused the spirit of Cyrus, king of Persia.

Luke 8:16-18: No one lights a lamp to put it under a bed.

To be a martyr is to be a witness. That presupposes something, someone, we’re witnessing to. The Korean martyrs—women and men, clergy and laypeople, young and old—give a luminous example in this regard. They held on to their Christian faith with astonishing clarity. What prepares one for such heroic steadfastness?

The birth of the Korean Church is fascinating. It was born without missionaries, through an existential thirst from within, a thirst for something more than existing structures, institutions, customs could provide. The first believers were young people concerned to understand what life is about. A few Christian books smuggled into Korea from China presented a staggering possibility: a God who loved all people equally, whose gift of grace is boundless.

The encounter with this proposition gave a thirst for more. Groups formed to study the faith; new literature was procured. In 1784 one young man, Yi Sünghun, was able to visit China where he encountered Catholic missionaries. He was baptised, then returned to Korea with Bibles, crucifixes and catechetical images. The foundation had been laid. On it grew a sturdy structure whose cement was the sheer otherness of Christ’s promise. To be a Christian, it was understood, was to be human differently.

This freeing difference, lived out in ordinary lives, proved irresistibly attractive to searching souls. It was hated by a state that depended on control. Thus was forged the fortitude expressed in St Andrew Kim’s final exhortation in 1846: ‘Follow the will of God, fight with all your heart for our divine leader Jesus […]. Do not forget fraternal love, help one another, persevere.’ Having spoken, he gave himself over, serenely, to his executor.

We worry a lot, these days, about the collapse of structures and falling numbers. We do well to worry. Let us not, though, yield to the temptation of just condemning the ‘world’ that ignores, even despises, us. Let us rather ask: does the Christian proclamation find credible expression in our lives? Does it stand for something else, something greater, more substantial, more beautiful than the world’s fragile promises? Does it transform us?

The thirst for meaning that awakened the early Christians of Korea and led them, over time, to the stature of martyrdom, is still abroad in our world: indeed it is an often almost desperate thirst. Let us listen out for its confused expressions; let us channel living water towards it. Let us never forget that, if the Lord has given us the light of faith, it is so that it, through us, may be carried into dark places, not just to cast a cosy, homely glow under our own bed.