A Venetian in Buda

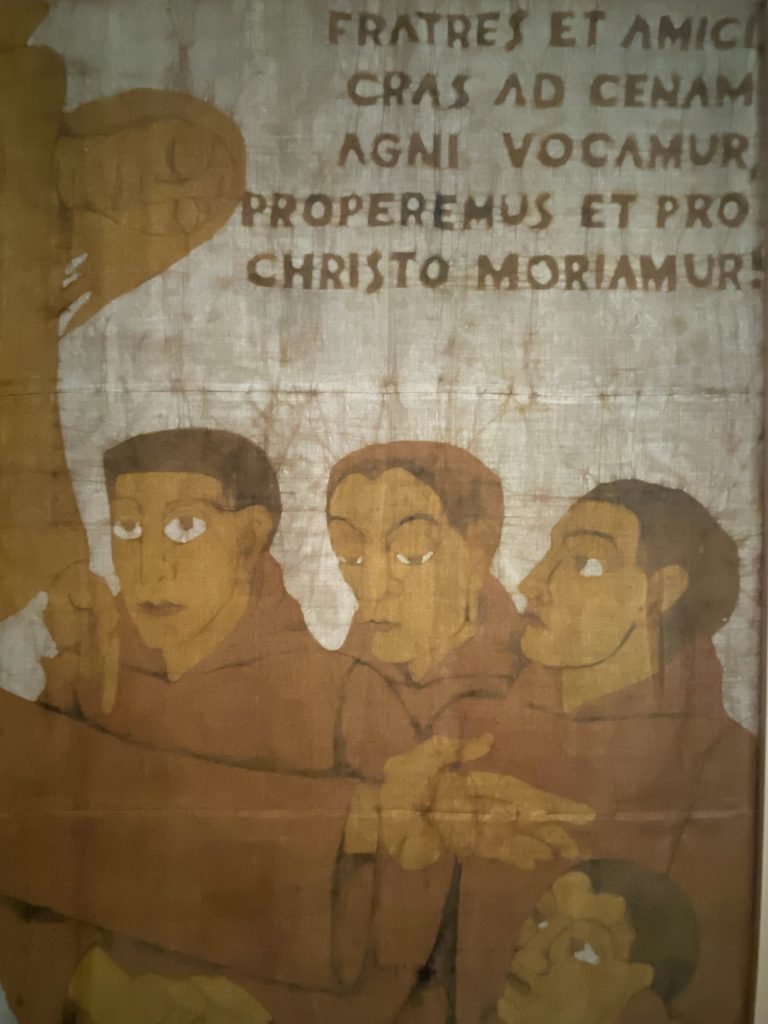

Walking into the refectory of the Benedictine community of Saint Sabina in Budapest this afternoon, I was struck by the large mural on the wall that shows St Gerard Sagredo, the Venetian monk who became the first bishop of Csanád, addressing his brethren on the eve of his death: ‘Brothers and friends! Tomorrow we shall be called to the supper of the Lamb. Let us make haste and die for Christ!’ The story of Gerard is gripping for several reasons. It shows the European network that underpinned medieval Catholicism, at once enabling and relativising nationhood; it shows the role monasticism played in evangelisation; and it gives credible, amiable human features to an age often presented as lost in mythic mists. Gerard was consecrated a bishop the year St Olav died at Stiklestad, in 1030. He died on 24 September (so his feast is today) in 1046. The sanctoral constantly helps us to place ourselves within a long historical continuity. The way the world is developing at the moment, that is a gift to cherish, and to share.

Sammenheng

I dag morges fikk jeg feire messe i Trondenes kirke. I sin nåværende form ble den påbegynt omtrent da Saint Louis var konge i Frankrike. Kirken ble bygd nær Laugen, innsjøen hvor de første kristne her i Harstadtraktene sies å være blitt døpt i 999 av den engelske Biskop Sigurd, som fulgte Olav Tryggvasson.

Det utsøkte alterskapet over høyalteret ble til i Lübeck på 1400-tallet. Det viser Guds Mor flankert av kvinnelige slektninger, understøttet av mannlige. Ikke bare fikk dette kunstverket stå uforstyrret gjennom reformasjonen i det sekstende århundre; det er forblitt det naturlige midtpunkt i et kirkerom som siden 1530-tallet formelt har vært luthersk.

Iblant må men en tur ut i periferien for å se store linjer som lett blir uklare i kontroversenes episentre. Derved får man hjelp til å sette mangt, også seg selv, i sammenheng.

No Soppy Thinking

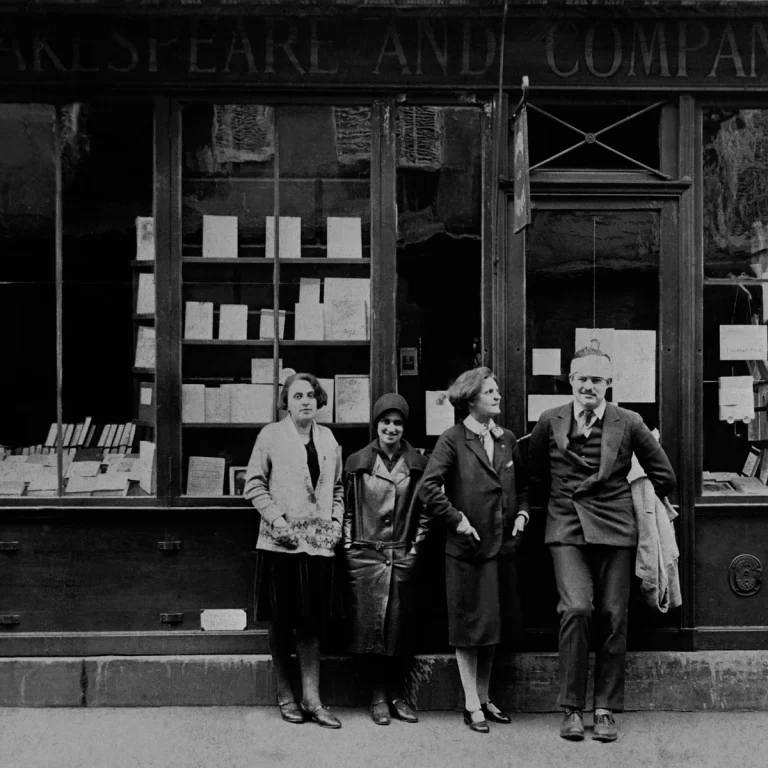

Hemingway and AI

Hemingway on the creative process: ‘I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, «Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.» So finally I would write the one true sentence, and then go on from there. It was easy then because there was always one true sentence that I knew or had seen or had heard someone say. If I started to write elaborately, or like someone introducing or presenting something, I found that I could cut that scrollwork or ornament out and throw it away and start with the first true simple declarative sentence I had written. Up in that room I decided that I would write one story about each thing that I knew about. I was trying to do this all the time I was writing, and it was good and severe discipline.’ An exercise AI could never accomplish. It matters to have ears attuned to the true.

Nativity of Mary

Today’s feast invites us to consider that God, who entered history as male, with a gendered specificity that cannot be abstracted; that this God who became man and a man, in whose image and glory we are called to have a share, began his existence in a woman’s womb. The biological process remains a paradigm for ecclesial life. Christ’s birth is both an historical datum and a continuous mystery of transformation. It was not by coincidence that Christians of antiquity adorned the apses of their churches, just above the altar, with wondrous representations of the Theotokos. The Church, Lumen Gentium teaches us, is Marian in essence. This, too, points to a gendered specificity that seeks coherent expression. Only therein will we as believers and members of the Church, whether we are women or men, find our true, essential form. In this symbolic, sacramental interaction of masculinity and femininity, fundamental to Catholic life, we shall find, of this I am convinced, the true response to painful perplexities present in our time. This response is already formulated, thank God; it needn’t be invented anew. From a homily for 8 September.

Orin O’Brien

Molly O’Brien’s film about her aunt Orin, the first woman member of the New York Philharmonic, produced when the legendary double bassist was 88 (though she comes across, quite naturally, as been fifty-something) is a marvel — don’t mind its being on Netflix and sponsored by The Secular Society. It gives you a compelling account of a life convincingly lived with passion, vulnerability, and disarming self-irony. Orin would tell her students to treasure the sound of their instruments, ‘but if there’s anything else you enjoy as much as playing the bass, by all means, do it’. That’s good vocational discernment. Looking back, she offers her ‘theory of how to enjoy your life incredibly’: the secret is not to ‘mind playing second fiddle’, loving what you do so much that you do it for its own sake, never mind whether or not you get rapturous applause.

En Fanfare

On a long flight this summer, I breathed a sigh of resignation after scanning the list of 154 films on offer, ascertaining there wasn’t a single one I’d prefer to the imperceptible movement of the mini aeroplane on the virtual map. Then I looked again, and found a jewel. I’d read a review of Emmanuel Courcol’s En Fanfare, but hadn’t associated it with ‘The Marching Band’, the English title. The press has described it as ‘an archetypal feel-good story’, but that does not do it justice. The film offers an exploration at once fond and searing of identity and belonging. It is immediately accessible, yet profound. It made me laugh and cry to the extent I thought I was disturbing fellow passengers – which I might have done, had they not been asleep. The Times called it an ‘almost Rousseauesque examination of nature versus nurture’. Where Rousseau proceeded by categories, though, Courcol, developing his theme musically, brings forth harmony and counterpoint where you might not expect it.

Prodromos

Given the importance of the event we commemorate, we cannot fail to be struck by the squalor of its circumstances. We know King Herod from several passages in the Gospel, also from Josephus and other historians. We know him to be a weak ruler, conceited and unprincipled. How gladly he listened to John! How cavalierly he ignored what he heard! Over and beyond such spinelessness, today’s account presents him in a light that is positively lurid. Reclining at an executive luncheon, he is so enthralled by the suggestive charms of his stepdaughter that he promises to give her anything —well, almost anything—to show his appreciation. The gruesome request that followed shook him, yet Herod was bound by his word, his vain and presumptuous word. John was executed forthwith, with the guests still at table. A lecherous king, a jealous queen, a fickle child: should these bring the Old Testament to a close?

From a sermon for the feast of the Beheading of John the Baptist.

Single-Mindedness

We remember St Monica, the mother of Augustine, for her tenacity — and she certainly had character. More essential still, though, was her perseverance in prayer. Powerful are the words she spoke to her son the day before she died, recorded in Augustine’s Confessions: ‘What I am doing here still, or why I am still here, I do not know, for worldly hope has withered away for me. One thing only there was for which I desired to linger in this life: to see you a Catholic Christian before I died.’ Our prayer should be universal, cosmic; it should embrace the whole world. At the same it is good to adopt a personal intention as ours particularly, keeping it ever aflame before the Lord, like a sanctuary lamp carefully tended. If we did, who knows what blessed transformations might take place.

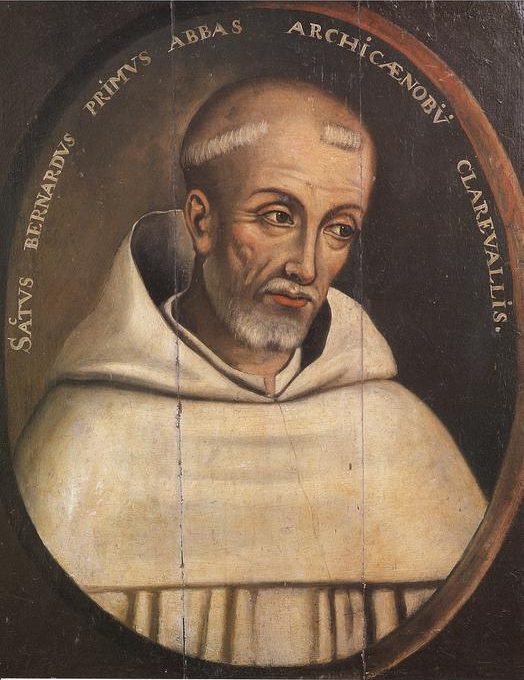

St Bernard

As a young abbot, Bernard was aflame with ‘a maternal love for all mankind’. He saw what urgent work there was to do in the Church. He eagerly wanted to perform great things. Thereby ‘desire and humility were at odds’. Not only did he overestimate his own strength; he asked too much of his brethren. Such was his aura that ‘he frightened away almost all those among whom he was coming to live as abbot’. Instead of feeling drawn to him as to a source of life, they felt repulsed. Bernard, whom grace had preserved from some of the heart’s most devious temptations, was horrified to learn of the squalid inner battles many monks had to fight. He spoke to them harshly, to the point of ‘[seeming] to sow seeds of despair in men already weak’. Like Adam in Eden, he presumed that a graced state of pure divine gift was somehow his by right, entitling him to judge less favoured men. With time, though, transformation came upon him. It was wrought by his brethren’s fidelity.

More

Paul Cavill writes: ‘If everyone has one book inside them, then perhaps inside every scholar of the Tudor period is a biography of Thomas More. The temptation is great, so perfectly does his trajectory encapsulate the reception of the Renaissance and the early Reformation in England. More’s death is irresistibly moving, even if we have run out of original ways to recount a Tudor beheading.’ Cavill, who teaches modern history at Cambridge, evokes More’s ‘combination of ribaldry and erudition, his way with dialogue, his pointed jests and merry tales, his sardonic wit, his loathing of pride, his touchiness, his flintiness, his capacity to harden his heart, his adamantine conviction. The chronicler Edward Hall captured a trait when he observed disapprovingly that More “thought nothing to be well spoken except he had ministered some mock in the communication”. But he paid an unintended compliment by dismissing More as either “a foolish wise man or a wise foolish man”, for More was convinced that the difference between wisdom and folly was merely a matter of worldly convention that would ultimately be inverted in heaven.’ A man for all seasons.

Where the Wind is Blowing

I am grateful for Massimo Faggioli’s thoughtful critique of a recent paper I gave. I invite you to read it. Were I to offer a brief antiphonal response, it would be by way of three remarks. First, a bishop belongs by definition to everyone, not to an elite of whatever colour: his task is to seek the truth and to speak it in charity wherever he is called, in season and out of season. Secondly, my contribution was principally about the Nicene creed, not about Vatican II. A couple of statements about the council did need development. It is great that Dr Faggioli picks them up, notably the complex, important question of hermeneutics. Thirdly, my reference to tediousness concerned not sometimes fraught, earnest processes of dialectic enquiry, but the mud-slinging of which we have seen rather too much.

Regarding the liberal-conservative dichotomy, I love the statement made by Fr Elmar Salmann in his marvellous discourse of farewell to Sant’Anselmo, where for 30 years he taught students to think, and to delight in thinking: ‘Perhaps we might say […] that my way of proceeding has been neither conservative nor liberal but rather classical and liberating [classico e liberante].’ Now that’s a statement apt to air out a stuffy room — and an aspiration I share.

Sixtus

Pope Sixtus II is mentioned in the Roman Canon. I used to find the lists of saints in the Canon dull. Others must have felt the same, else the Missal would not have given the option of cutting them. As the years passed, though, the names came alive, each redolent with a personal story, a presence. The lists are now very dear to me. I feel a stab of pain when they are shorn. Pope Sixtus II was pope for less than a year in 257-8, a generation after the death of St Cecilia. He was St Lawrence’s bishop. Both were killed on the orders of Valerian, the emperor, four days apart. Sixtus was preaching to the people when soldiers came and dragged him away to be beheaded. A century later Pope Damasus placed an epitaph on his tomb. It begins: Tempore quo gladius secuit pia viscera Matris hic positus Rector caelestia iussa docebam, ‘At the time when the sword pierced the Mother’s pious bowels I, the [people’s] guide, lying here, was expounding the divine commandments.’ His feast invites us to remember thankfully all those bishops of Rome who have stood firm when impious arms have sought to molest Mother Church. They instantiate Christ’s promise to Peter, showing that the Church is built on Rock and that ‘the gates of the netherworld shall not prevail against it.’

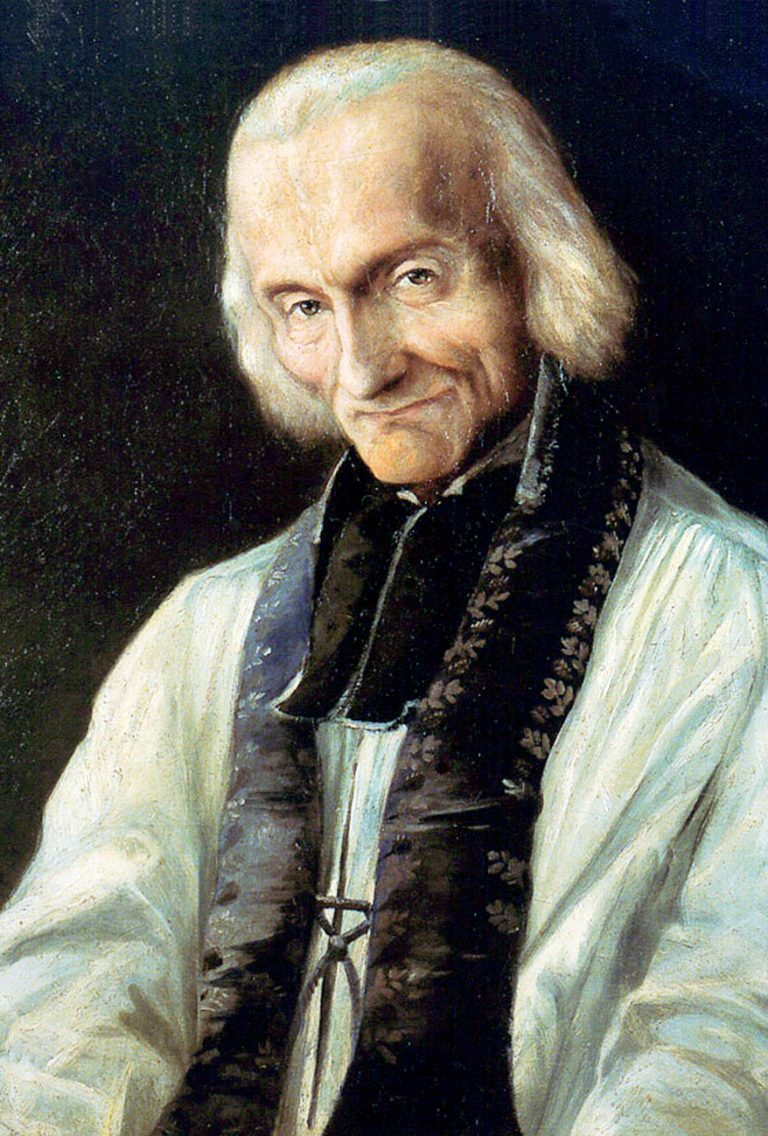

Curé d’Ars

Den hellige Jean-Marie Vianney var enestående pastoralt begavet. Hans store budskap gjaldt det kristne kall til hellighet, ja, til guddommeliggjørelse. Det var grunnleggende for Vianney (som for Det nye testamente) at den kristne kalles til deltagelse i Guds eget liv. Syndens tragedie bestod for ham i dét, at den hindrer det guddommelige liv i mennesket og slik fremmedgjør det fra målet det er skapt for, fra å kjenne salig glede. Tenk på et utsagn som følgende, fra en av Vianneys prekener: ‘Lik en vakker hvit due som flyr ut fra vannene for å riste sine vinger over jorden, utgår Den hellige Ånd fra den guddommelige fullkommenhets uendelige hav for å slå med vingene over rene sjeler, for å inngi dem kjærlighetens balsam.’ Det kaller jeg forkynnelse! Kunne vi ikke trenge å få et slikt budskap oftere lagt på minnet?

Temptation

How can we face serious temptations?

First of all by learning what it is to live on trust: when a temptation comes, to recognise it honestly and to evaluate it—see what sort of response is needed—then, even if it makes me frightened or even terrified, to remember that it doesn’t have the last word. Also, that this particular temptation, even if it may haunt me, doesn’t define me, and that I’m called and enabled by nature and grace to pass beyond it. Because temptations only become really mortiferous when I fall for the illusion to think that, «Gosh, this is it; this is reality now—this temptation.» That’s where despair raises its ugly head. One of the things the Fathers do is to help us recognise temptations, and they do that forensically with great specificity. At the same time, they help us to despise them, and sometimes they will laugh at temptations. They will say, «Ha ha, you think I’m going to fall into that trap again?» And often enough, at that, the devilish plot just dissolves into thin air or the demons take flight.

From the Desert Fathers Q&A session of 7 July, now available as a transcript here.

Seeking Truth

The coincidence of today’s Mass readings is revealing. The 600,000 men (not counting their families) who go up from Rameses to Succoth represent the truth-and-freedom-seekers of all times, vigorously on the march (Exodus 12.37ff.). What happens, though, when liberating Truth turns up in person? People plot against him, want him out of the way, ‘discussing how to destroy him’ (Matthew 12.14ff.).

It is an aspect of our fallen nature at once tragic and absurd: the tendency consistently to miss our goal and forfeit homecoming, opting instead for fruitless gyrovaguery. Great attention is needed in this area. Setting out from a given captivity is one thing; remembering what the journey’s destination is (and what freedom is like) is another.

In Memoriam

The latest issue of Pluscarden Benedictines, always readable, reprints Bishop Hugh‘s homily at the requiem for Fr Maurus twenty years ago, after he disappeared mysteriously. It is a beautiful, affectionate, shrewd re-reading of a remarkable life that blessed countless people. Who was Fr Maurus? An ‘energetic, self-possessed, single-minded, masterful man, sometimes severe, often hilarious, detached and so warm, rough and gruff but capable of heart-rending kindness, full of himself but never selfish, full of Christ, full of Mary, full of the Bible, full of stories, often frustrated, always content, silent and full of pithy, punchy words that went to your heart, sometimes uncannily perceptive, always with a mystery to him’ – above all one ‘visibly outstandingly faithful to prayer’. His disappearance after years of dementia, ‘already a form of disappearance’, was somehow characteristic: ‘He once said to me, I hate goodbyes’. ‘Fr Maurus, loyal as he was, was always bigger than what he did, more than what made him. He had prayed and built this community for 58 years, it was time to go to God.’ Requiescat!

The Region Where One Loves

In adolescent novels, no trespass is more dastardly than that of reading another’s intimate journal, all those entries beginning, ‘Dear Diary’, containing outpourings of contemplative hearts. There are diaries, though, written with a readership in mind, be it a future one. Such are those of A.C. Benson, son of E.W., archbishop of Canterbury, and brother of R.H., Catholic priest and apologist. A.C. decreed that his 180 personal notebooks should be locked away for fifty years post mortem. That term has long since passed: he died in 1925. D.J. Taylor recently wrote a splendid review of The Benson Diary just out, edited by Eamon Duffy and Ronald Hyam. I smiled at cited character studies like those of Talbot Peel ‘in whose veins runs the blood of generations of maiden aunts’ or of a noxious brandy-swilling woman met on a train to King’s Lynn in whom A.C., as the train advanced, discerned a vulnerable person ‘so anxious & sore stricken at the perils of the journey, & so resolved to safeguard her own health & comfort’ that she needed a tot now and again. Really striking is this confession in the first person: ‘The only fine things come out of the lonely part of the mind – out of the region where one loves and hopes – the stale things come out of the place where one jostles & scores off people.’

Nightingale

The ancients had an affinity for birds. Unexposed to our modern registers of fancy which let us broadcast our own voice, which let us fly, they were sensitive to birds’ fragility and strength, enchanted by the strangeness they bring near human society. I marvel at this poem in which Alcuin of York (740-804) mourns the disappearance of a nightingale that used to cheer him at night. Alcuin knew the greatest, most influential people of his age, including Charlemagne. He is said to have been the learnedest man of his generation. Yet he took the trouble to write this epitaph to a vanished wild creature. Thanks to it, we can hear the echo of its singing yet.

From Mediaeval Latin Lyrics by Helen Waddell.

Christian Politics

What do Christian politics look like? The question concerns us all. I thought of it while watching this recent Q&A session in the German parliament. One question (at ’49) concerns the controversial nomination of Frauke Brosius-Gersdorf as judge in the Federal Constitutional Court, emblematic of confrontations taking place in many countries throughout the western world. Mrs Brosius-Gersdorf has a stated a priori position that human dignity does not apply wherever human life exists; on that basis she supports, for example, the provision of abortion until term. In the Q&A the chancellor, Friedrich Merz, who represents the Christian Democratic Union, is asked whether he can in conscience support the nomination to this critical position of an individual for whom a nine-month-old foetus two minutes before birth has no human dignity ascribable to it. The chancellor answers monosyllabically: ‘Yes’.

And I was led to reflect, with regard to the question with which I set out: Surely not like this.

Summer Break

Coram Fratribus will take a holiday for a couple of weeks. Thank you for visiting the site. I hope you get something from it.

With best wishes,

+fr Erik Varden

***

I remember one day in June.

The height of summer and the sun

still rising on one of those days

that calls all nature into song.

R.S Thomas

La Traviata

Works of art affect us in different ways at different stages of our lives. Seeing La Traviata this evening I was moved, of course, by the drama of Violetta, a character showing that it is possible for the leopard to change its spots and for a life to begin again on fresh terms; but I was especially struck by the late insight of Germont, Alfredo’s father, who for the sake of social ambition forced apart two people who loved one another and were able to make each other happy. Owning his mistake he exclaims: Oh, malcauto vegliardo! Il mal ch’io feci ora sol vedo! — ‘Oh, rash old man! Only now do I see the harm I have done.’ It’s way too late, though.

Oh, to weigh the consequence of one’s words and actions in due time.

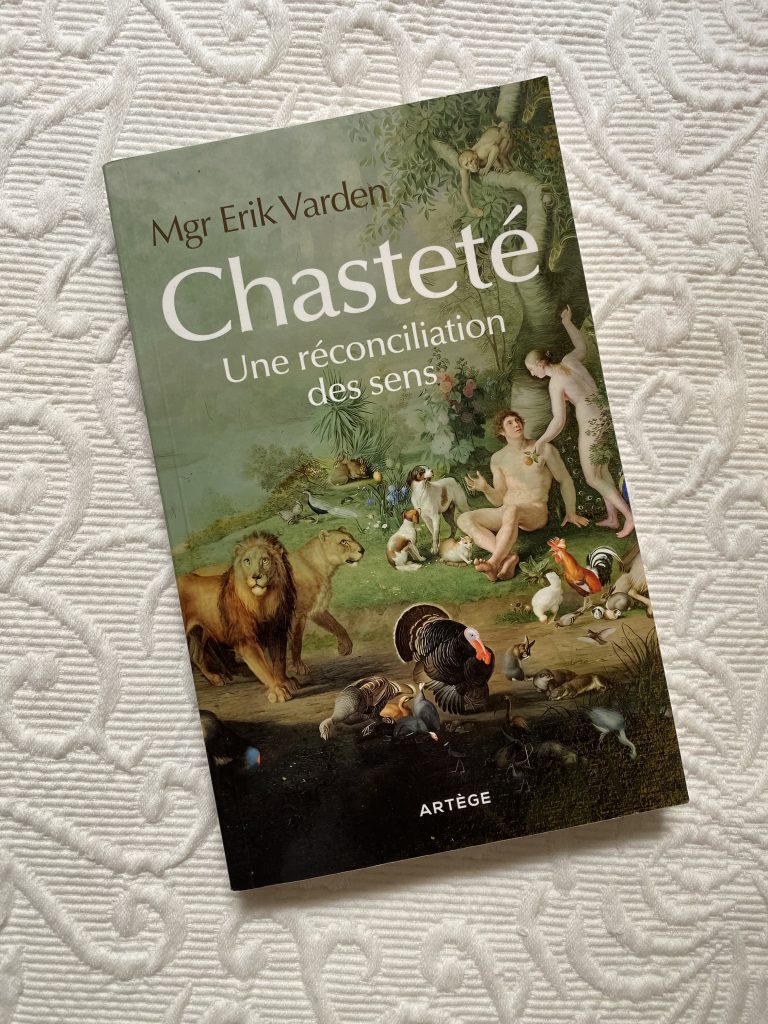

Chastity in French

My book Chastity was recently launched in a fine French translation published by Artège.

On that occasion I was invited to present it in a number of media, in conversation with Vincent Roux of Le Figaro, with Aymerick Pourbaix in En quête d’Esprit, with Cyriac Zeller of Famille Chrétienne, a magazine that also dedicated an article to the subject in its print edition.

‘We progress with patience from what is partial to what is whole, ordering and making chaste our bodies, souls and minds in the obedience of charity. The eyes of our love are opened thereby. We pass from blindness to sight. The journey is laborious at times, but leads through lovely landscapes. The further we travel, the more keenly we are conscious that we do not walk alone.’

You may be interested in this thoughtful review of the English volume by Harry Redhead.

Corpus Christi in Toledo

I have had the privilege of celebrating Corpus Christi in Toledo. It is like nothing else, not only on account of the splendid pageantry, of the streets strewn with scented herbs, of the famous monstrance that holds an ostensorium Isabelle of Castille had made with the first gold brought back from America, of the tapestries adorning houses in which locals stand on balconies throwing handfuls of rose petals; all this is beautiful and impressive. What pierces one’s heart, though, is the corporate, tangible focus on the spectacle’s Protagonist – the Lord of the world sacramentally present in the Sacred Host, greeted at each turning of the winding, narrow streets with applause while people kneel in reverence. None of the mighty of this world would be greeted thus. Never before have I seen so clearly that the Corpus Christi procession manifests the mystery we celebrate on the final day of the liturgical year, when we venerate Christ as Universal King. I shall never forget this day. Edgar Beltrán from The Pillar was in Toledo, too. You can read his account here.

Accepting Mercy

How striking is this panel from a door in the Jesuit church in Büren, artwork from the mid-eighteenth century. The parable of the Prodigal Son is presented, quite as in the sermons of St Bernard, as a universal parable of redemption. The palace is an image of eternity. The father steps across its threshold to call and embrace his long-lost child, freed now of illusions of self-sufficiency. The prodigal’s ragged clothes suggest his inward poverty in spirit, making him apt for the kingdom of heaven. The elder son, meanwhile, by his outfit attuned to his environment, stands ready with hat and coat to leave desertwards. He remonstrates with the servant bringing a ring for the prodigal’s finger, unable to endure an environment founded on mercy, not computation.