Ord Om ordet

1. Påskedag

Acts 10:34, 37-43: God was with him.

1 Corinthians 5:6-8: Christ, our paschal lamb, has been sacrificed.

John 20:1-9: Till this moment they had failed to understand the teaching of Scripture.

How can we conceive of the resurrection from the dead? Christians have struggled with that challenge for centuries, notably since the Renaissance, when a taste for realism was established in the West and we began to develop the scientific mindset that wants to grasp how things work. Fifteenth-century painters show Christ literally rising out of death, standing up from a stone coffin, one foot within, one foot outside, his hand holding a banner of victory. A century or two later, naturalistic settings with elaborate tombs are in vogue, with the Lord coming forth robed in white, all gleaming and unworldly. In modern painting, the resurrection is sometimes portrayed by means of allusion: we are shown the rolled-away stone, the scattered linen cloths, the guard soundly asleep; but the protagonist, Christ, is paradoxically absent. We must draw the inference ourselves: he is not there, so must be risen. Films have shown Jesus’s rising by explosions of light, though his cosmic victory is muffled, rather, by its too close resemblance to the happy end of countless other movies. The trouble is: since resurrection, as of yet, is an event that lies beyond the realm of experience, we can’t know what it is like. Neither science nor imagination is of much help.

It may be wiser, then, to do what the early Church did, and think of Christ’s Pasch in terms of symbols drawn from Scripture. We have just heard what happened to John when, on Easter Day, he saw and believed: he began to make connections. ‘Till this moment’, he says, he and his friends ‘had failed to understand the teaching of Scripture.’ The resurrection opened their eyes. Their meeting with the risen Christ made them embark on a re-reading of the entire wide sweep of God’s dealings with mankind. They found it wholly geared towards the Easter events they had witnessed. They were sure they had found the key to history. And so they set about seeking ways to make explicit this coherence of God’s plan for our salvation, to be seen in terms of promise and fulfilment. One way of doing this was by developing two biblical images: that of the shepherd and that of the lamb. Both are present in today’s solemn Mass.

‘Christ our paschal lamb has been sacrificed.’ St Paul’s assertion constructs a carrying arch from Pharaoh’s Egypt to Roman Palestine. The paschal lamb was slaughtered on the eve of Israel’s exodus. Its blood, smeared on door-posts, saved Israel’s sons from the Lord’s scourge of wrath. The lamb’s meat gave them strength to set out for home. Reenacted as ritual, the paschal meal came to express God’s covenant with Israel. It stood for election. It stood, too, for vicarious sacrifice: a dumb beast offered in atonement for the faithlessness of men. The public life of Jesus began with John’s cry, ‘Behold the Lamb of God!’ What the evangelists suggest, St Paul makes explicit: the first lamb was a type, meant to foreshadow a definitive salvation, brought by Christ. As a lamb Christ bore the burden of our sin. As a lamb he was offered in covenantal sacrifice. As a lamb he shed his blood for us and gave us his flesh to eat.

If the lamb could assume such significance to Israel, it was because they were a nation of shepherds. The patriarchs are inconceivable without their flocks. Their ecstasies and epiphanies were all accompanied by bleating. It was natural to them to think of God, too, as a Shepherd, and of themselves as his flock. The image occurs in the five books of Moses. It is later developed by the Prophets. In the Psalms, we find it constantly. ‘The Lord is my Shepherd, there is nothing I shall want.’ No passage of the Bible is better loved, more fondly sung. In John’s Gospel, Christ claims for himself the shepherd’s title. His last recorded words are a committal of his flock.

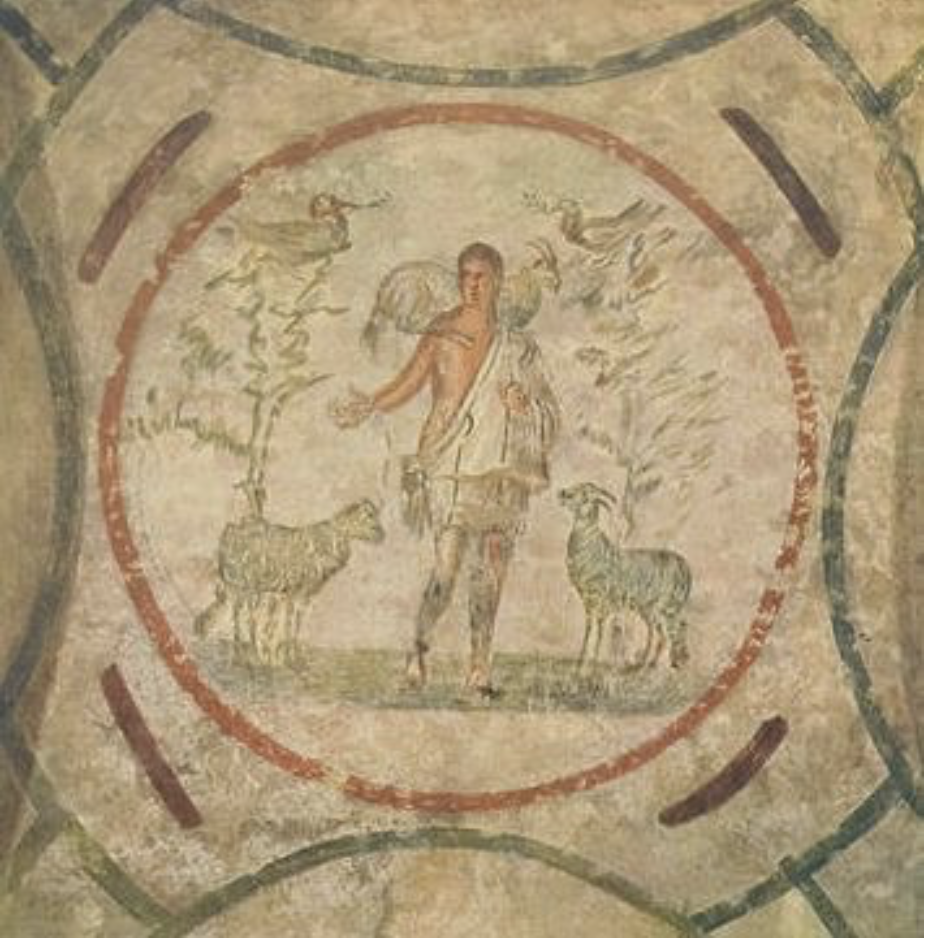

And so the Church’s mind could proceed with its wonderful synthetic flair. It is expressed in our Easter Sequence, which tells us, first, that ’the sheep are ransomed by the Lamb’; then, that Christ, like a good Biblical herdsman (who does not follow but precedes his flock), ‘goes before you into Galilee’. Our Saviour is a Lamb who is a Shepherd! Such is our Easter proclamation. This liturgical audacity is reflected in early Christian art. It is as Shepherd we find our saving Lamb depicted on the walls of Roman catacombs. In those monuments to resurrection hope, he is there, at once vulnerable and strong, guiding his own, one by one, through the bitterest valley of all, that of death, having given himself as pasture for his flock. ‘The Living Lamb’, sings St Ephrem, ‘has trodden out the path from the grave for those who lie buried.’ The victim is in fact victorious. The one who was slain stands before us as slayer, the slayer of death, his and ours.

How the resurrection took place we shall know only in the life to come. We must be patient. What we know now is that it happened. Death has lost its sting, sin its power. We are surrounded by a cloud of witnesses. Indeed, we are part of that cloud, for we, too, have eaten and drunk with him after his rising from the dead. That should be a cause for exultant joy this day and every day. Alleluia!