Summer Break

Coram Fratribus will take a holiday for a couple of weeks. Thank you for visiting the site. I hope you get something from it.

With best wishes,

+fr Erik Varden

***

I remember one day in June.

The height of summer and the sun

still rising on one of those days

that calls all nature into song.

R.S Thomas

La Traviata

Works of art affect us in different ways at different stages of our lives. Seeing La Traviata this evening I was moved, of course, by the drama of Violetta, a character showing that it is possible for the leopard to change its spots and for a life to begin again on fresh terms; but I was especially struck by the late insight of Germont, Alfredo’s father, who for the sake of social ambition forced apart two people who loved one another and were able to make each other happy. Owning his mistake he exclaims: Oh, malcauto vegliardo! Il mal ch’io feci ora sol vedo! — ‘Oh, rash old man! Only now do I see the harm I have done.’ It’s way too late, though.

Oh, to weigh the consequence of one’s words and actions in due time.

Chastity in French

My book Chastity was recently launched in a fine French translation published by Artège.

On that occasion I was invited to present it in a number of media, in conversation with Vincent Roux of Le Figaro, with Aymerick Pourbaix in En quête d’Esprit, with Cyriac Zeller of Famille Chrétienne, a magazine that also dedicated an article to the subject in its print edition.

‘We progress with patience from what is partial to what is whole, ordering and making chaste our bodies, souls and minds in the obedience of charity. The eyes of our love are opened thereby. We pass from blindness to sight. The journey is laborious at times, but leads through lovely landscapes. The further we travel, the more keenly we are conscious that we do not walk alone.’

You may be interested in this thoughtful review of the English volume by Harry Redhead.

Corpus Christi in Toledo

I have had the privilege of celebrating Corpus Christi in Toledo. It is like nothing else, not only on account of the splendid pageantry, of the streets strewn with scented herbs, of the famous monstrance that holds an ostensorium Isabelle of Castille had made with the first gold brought back from America, of the tapestries adorning houses in which locals stand on balconies throwing handfuls of rose petals; all this is beautiful and impressive. What pierces one’s heart, though, is the corporate, tangible focus on the spectacle’s Protagonist – the Lord of the world sacramentally present in the Sacred Host, greeted at each turning of the winding, narrow streets with applause while people kneel in reverence. None of the mighty of this world would be greeted thus. Never before have I seen so clearly that the Corpus Christi procession manifests the mystery we celebrate on the final day of the liturgical year, when we venerate Christ as Universal King. I shall never forget this day. Edgar Beltrán from The Pillar was in Toledo, too. You can read his account here.

Accepting Mercy

How striking is this panel from a door in the Jesuit church in Büren, artwork from the mid-eighteenth century. The parable of the Prodigal Son is presented, quite as in the sermons of St Bernard, as a universal parable of redemption. The palace is an image of eternity. The father steps across its threshold to call and embrace his long-lost child, freed now of illusions of self-sufficiency. The prodigal’s ragged clothes suggest his inward poverty in spirit, making him apt for the kingdom of heaven. The elder son, meanwhile, by his outfit attuned to his environment, stands ready with hat and coat to leave desertwards. He remonstrates with the servant bringing a ring for the prodigal’s finger, unable to endure an environment founded on mercy, not computation.

Setting out to Sea

I read Adam Nicholson’s wonderful book on Homer years ago, in Cameroon. Recently I came upon this essay, ‘Sailing with the Greeks’, in The Plough. He remarks how Western thought has long unfolded in a terranian framework. It has been on ‘a long campaign to establish “foundations” for what it does. No thought can be valid without some meaty “groundwork” having been laid. “Grounds” are where truth is thought to begin.’ What if, instead, we attuned our thinking to the sea? ‘When lying on a sofa or having lunch in a restaurant, nothing seems more obvious than our ability to choose. The menu of life encourages the illusion of potency and feeds the arrogance that comes in its wake. The boat is the opposite of that. It imposes a necessary modesty, a submission to the all too obvious reality of the defining situation around you. You can only do what the boat requires you to do. And in that compulsion, mysteriously, a sense of freedom flowers, one in which your life is momentarily liberated from the need to choose’.

Speech

One doesn’t expect an essay on Pentecost in a secular broadsheet, but that is what Carsten Knop, an editor of the FAZ, provided yesterday in a beautiful, wistful piece: ‘[Those present at Pentecost] recognise the power of human words. They notice that a divine origin shimmers behind words not destructively used: we are intended for relation with each other. The purpose of words is to live out relationship. To be endowed with language is not just about emitting grunts. We are able to confide in one another; we can establish connections and networks; we can enthuse each other, create shared knowledge and elevate ourselves in its light. That is the effect of the Power that, in the story which provides us with an extra holiday, is called Holy Spirit. Don’t laugh: anyone who has known what happens when people leave an auditorium amicably together in order, afterwards, to speak about what they have experienced, has had a sense of what it is about, not just at Pentecost. We must simply try to understand each other.’

Mary McCarthy

I recently picked up a copy of Memoirs of a Catholic Girlhood re-edited by Fitzcarraldo. I didn’t want it to finish. Gloriously written, each sentence of chiselled perfection, it displays McCarthy’s signature cynicism; yet at the same time it is tender. Often scathing of her childhood’s religion (‘In the Catholic Church, even the most remote eventualities are discussed with pedantic literalness’), she yet recalls exalted moments when ‘the soul was fired with reverence’. There is wonderful comedy in accounts of absurdities, pathos in the retelling of grief. She sums up the persona of an émigrée teacher remarking, ‘she took being Scottish personally‘. The self-irony is delicious: ‘My nose was my chief worry; it was too snub, and I had been sleeping with a clothespeg on it to give it a more aristocratic shape.’ The final essay, on McCarthy’s grandmother, lends this book greatness. I shall not forget the description of an intimate bereavement: ‘A terrible scream – an unearthly scream – came from behind the closed door of her bedroom; I have never heard such a sound, neither animal nor human, and it did not stop. It went on and on, like a fire siren on the moon.’

Where’s the Bar?

Listening to Fr Michael Suarez’s keynote address at UVA’s Final Exercises a couple of weeks ago, a clarion call for academic freedom and a reflection on the university’s role in society, I was struck by his reference to one of his teachers, Dorothy Bednarowska. He refers (at about ’16) to a run-in he had with her while still a research student. Critical of his priorities, she told him squarely: ‘You are wasting your time! You think the bar is here right in front of you, but excellence lies much higher, and you should be chasing it!’ Where, these days, are the voices, in society, in the Church, that urge us to pursue excellence? Does anyone still believe in it? Bednarowska, a founding fellow (alongside Iris Murdoch) of St Anne’s College in Oxford, taught generations of young people to read responsibly and intelligently. Content to let her students be her legacy, she never published. What is more, as an obituarist pointed out, ‘she actively enjoyed teaching’. Clearly formidable, she was unconcerned to leave a monument to herself. Hers is, in the best sense, a provocative legacy. I am glad to be confronted with it.

Reading Görres

In a post about Görres you wrote, “Hers is a crucial voice for the present moment.” What do you find “crucial” about Görres’ voice for Catholics today?

I like the fact that she is analytical, utterly unsentimental, yet acutely sensitive. A learned, intelligent woman, she was conscious of the riches of Catholic tradition, delighting in them; and she sought ways of making these known to her own times, proposing thoughtful answers to contemporary queries. She was lucid about the reforms of the 1960s, wary of facile optimism. Her notes from those years are a help to a serious, uncynical, hopeful rereading of history now.

From a recent conversation with Jennifer Bryson. See also previous entries here and here and here and here and here.

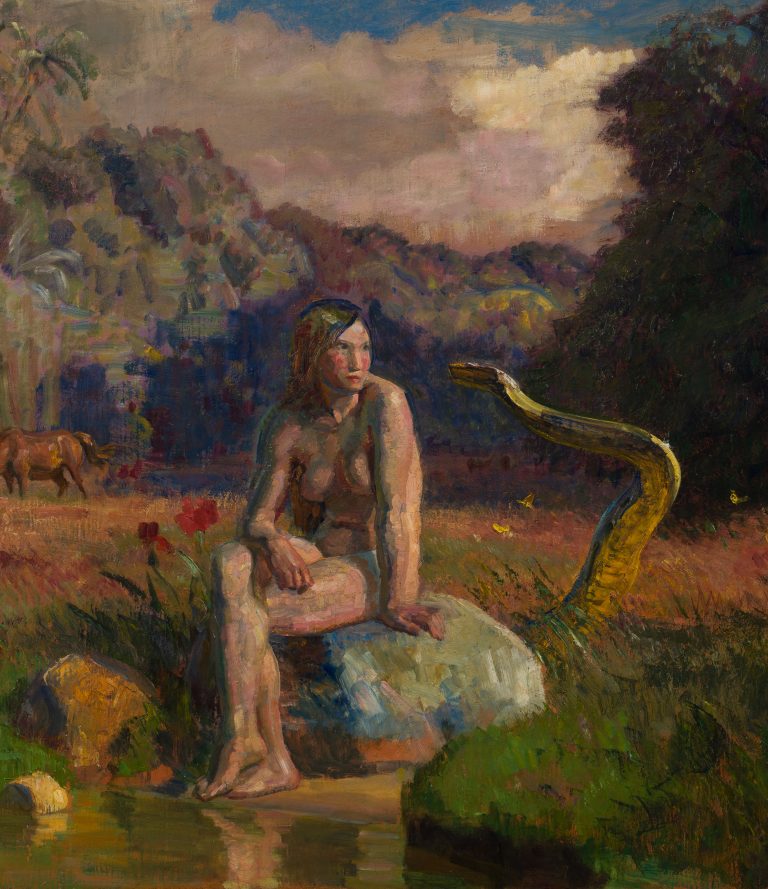

Eve

A generous art historian has introduced me to a painting by Joakim Skovgaard (1856-1933) of which you can here see a detail. It is at once faithfully Biblical and timelessly existential. It is Biblical in so far as it portrays the almost amicable conversation between Eve and the serpent as we find it related in Genesis 3. The tempter, in this account, gives no brusque commands to the woman. Instead he delicately subverts her perception, and so her judgement. He does this by gaining her attention and trust, speaking soft, flattering words. Often enough this is how temptation insinuates itself. It seems so innocuous, even somehow kind, surrounded (as the serpent in this canvas) by peacefully fluttering butterflies. So seductive can temptation’s voice be that we forget to look it in the face. Had Eve looked into her interlocutor’s eyes, would she have believed that his intention coincided with her flourishing?

Shoddy History

We tend to assume it is AI that will corrupt our sense of historical processes and contingencies. The fear is not unfounded. But shoddy, biased scholarship also has much to answer for. I am shaken to read, in a single issue of the TLS, the accounts of two serious historians (Robert Tombs and Felipe Fernández-Armesto) denouncing the work of their colleagues as well below par, ‘so self-indulgent, so partisan, so ignorant, so poorly written and so carelessly checked’. Tombs analyses what he presents as a rough-shod ride over historical truths determinedly pursued by the Fitzwilliam Museum and the Church Commission; Fernández-Armesto reviews with exasperation (‘I opened the book expecting instruction and entertainment, I closed it in despair’) ‘A New History of the New World’. The latter remarks: ‘We should be wary of wallowing in self-righteous judgements of the past: they will be visited on us in return.’

A Single Melody

On a journey this afternoon, I found myself in an airport lounge listening with tears in my eyes to the pope’s homily from this morning’s Mass of Inauguration: ‘In this spirit of faith, the College of Cardinals came together for the Conclave; assembling from a variety of background stories, from different itineraries, we placed in God’s hands our desire to elect a new successor to Peter, a bishop of Rome, a pastor able to safeguard the rich patrimony of Christian faith while at the same time looking far ahead, so to go out and encounter the questions, anxieties, and challenges of today. Accompanied by your prayers we were sensitive to the work of the Holy Spirit, who managed to tune the diverse instruments of music so that the chords of our hearts vibrated with a single melody.’ He went on to summon us all from discord to concord. May we heed that call.

The full text of the Holy Father’s homily is here.

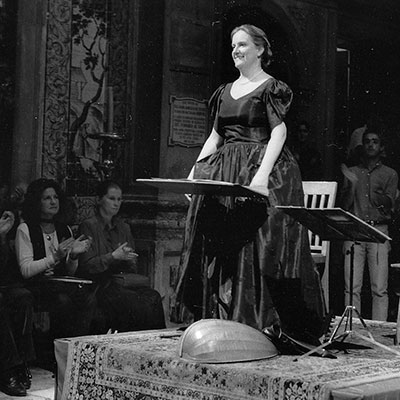

La Resurrezione

One of the joys of Eastertide is to listen to Handel’s oratorio La Resurrezione. It is a youthful work: the composer was 23 when it was first performed in Rome on Easter Sunday 1708, with an elite orchestra led by Corelli. As Graham Abbott has written, ‘It is in fact an unstaged opera on a religious subject, with a text by Carlo Sigismondo Capece, secretary to the Queen of Poland, who was exiled in Rome.’ Capece strikingly set the Christian drama with reference to both apocryphal and pagan traditions, showing forth Christ’s Easter victory as the culmination of even implicit hopes. This is a lovely recording. My favourite, though, is this, conducted by Minkowski, with Jennifer Smith singing gloriously in the role of Maria Maddalena.

Catholic

During the past eight days, attempts to predict what will be Pope Leo XIV’s priorities, method of government, and style have been legion. The lucidest, most helpful statement I have read so far appeared yesterday in an essay published by Daniel Capó in The Objective:

‘His own biography speaks to us, moreover, of a man who is truly Catholic in the sense of universal: North American and Peruvian, a scholar and a missionary, a mathematician and a canonist, a past superior of the Augustinian Order and a Vatican Prefect, a polyglot and a diplomat. Someone with this curriculum is unlikely to yield to the temptation of engaging in a culture war that is as divisive as it is, often enough, histrionic.’

Leo XIV

‘I am’, said our Holy Father this evening, addressing us for the first time as pope, ‘a son of St Augustine’ — of Augustine, that supremely intelligent, compassionate, yet uncompromising prober of the human condition, who knew how to orient hearts and minds towards God in such a way that his words resound still with undiminished power. Prosper of Aquitaine held Augustine forth, too, as an example of those ‘strong figures who could tame the unjust powers of the world and protect otherwise helpless communities from the ravages of war’. As another such instance he cited Leo the Great, who turned Attila away from northern Italy in 452 relying ‘on the help of God, who one should know is never missing from the labours of the pious.’ Augustine and Leo, consummate theologians, men of prayer and courage, orderers of chaos, keen readers of the signs of the times: these are the patrons of a new papacy. Long life to Pope Leo XIV!

Interessant rapport

A Review of evidence and best practice in the field of paediatric gender dysphoria published today chimes with a growing global consensus. It concludes: ‘A central theme of this Review is that many U.S. medical professionals and associations have fallen short of their duty to prioritize the health interests of young patients. First, there was a rapid expansion and implementation of a clinical protocol that lacked sufficient scientific and ethical justification. Second, when confronted with compelling evidence that this protocol did not deliver the health benefits it promised, and that other countries were changing their policies appropriately, U.S. medical professionals and associations failed to reconsider the “gender-affirming” approach. Third, conflicting evidence—evidence that challenged the foundational assumptions of the protocol and the professional standing of its advocates—was mischaracterized or insufficiently acknowledged. Finally, dissenting perspectives were marginalized, and those who voiced them were disparaged. While no clinician or medical association intends to fail their patients—particularly those who are most vulnerable—the preceding chapters demonstrate that this is precisely what has occurred.’ Cf. this statement from the Norwegian Council of Catholic Bishops produced in 2022.

Ut i været

‘Vinden blåser dit den vil, du hører den suser, men du vet ikke hvor den kommer fra, og hvor den farer hen.’ (Jn 3.8).

Hører du vinden suse uten å vite hvor den kommer fra eller hvor den farer hen, er det fordi du sitter innendørs, bak doble vinduer, med saueskinnstøfler og en god kopp te. Vil vi leve et åndelig liv, er det første som skal til at vi går ut i været.

Disiplene gjenkjente Jesus først som Guds Sønn midt i en storm so voldsom at de var skrekkslagne (Mt 14.22-33). Det er verd å tenke på ofte.

Klegg

“Todos, todos, todos” tilsvarer nok Guds hensikt. Velger vi oss så helheten på hans premisser, etter Kristi bud, for å være der hvor han, altets og alles Opphav, er? Dét er spørsmålet.

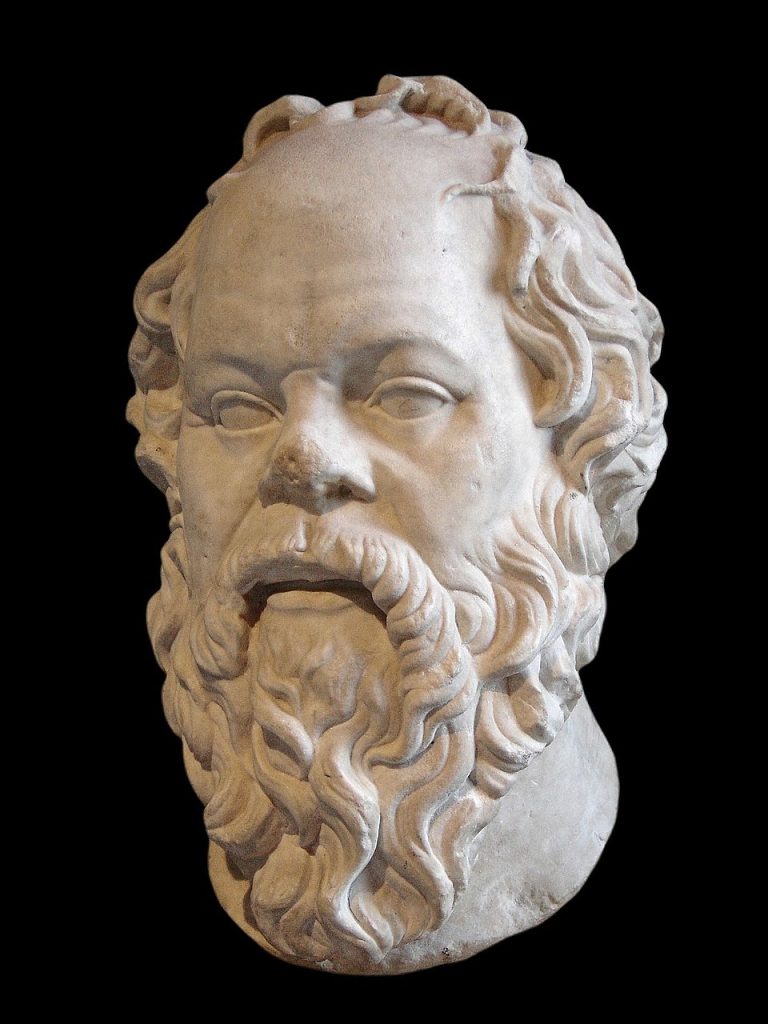

Filosofen Sokrates kalte seg selv en klegg hvis oppgave gikk ut på å drive samtidens athenere ut av uforstyrret selvgodhet. Pave Frans har hatt noe klegg-aktig ved seg. Det har ikke alltid vært bekvemt å ha med ham å gjøre. Han har utfordret oss, presset oss til å søke klarhet, i ulike sammenhenger, om hva ting handler om, for så å ta ansvarlige valg, for å leve troverdig som kristne. Nå har denne Herrens tjener fullført sitt jordeliv. For en bør han har båret!

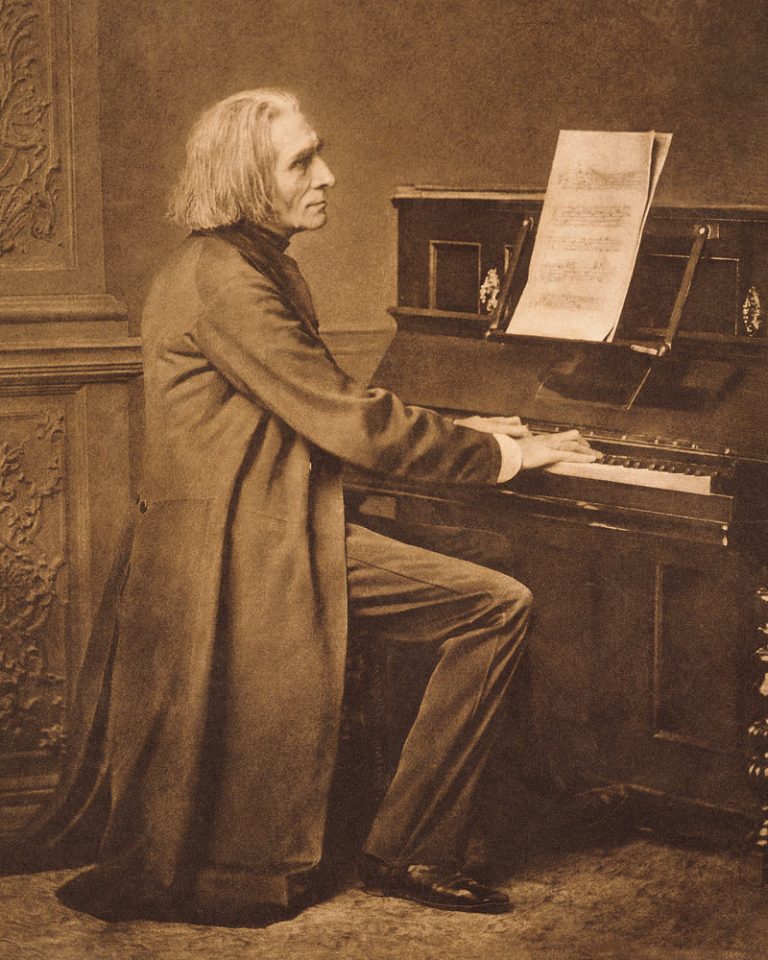

Via Crucis

Jeg husker hvordan jeg for drøyt tredve år siden stod i en platebutikk i Cambridge og høre et fabelaktig opptak av Liszts Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude fremført av Stephen Hough. Jeg kjøpte CD’en henført. Liszts sakrale, kontemplative stykker for klaver har altså geleidet meg gjennom mye av livet; men jeg hadde aldri hørt hans Via Crucis før jeg kom borti Leif Ove Andsnes’ nyslupne plate. Tolkningen er suveren. Musikken er essensiell, tilbakeholden. Ofte høres den ikke ut som Liszt, men autentisk er den, uttrykk for siste fase av komponistens liv – han var 68, og vigslet til kleriker, da verket ble fullført. Liszts Via Crucis ble uroppført i Budapest på Langfredag i 1929. Jeg lytter til den i dag etter å ha feiret Kirkens Pasjonsliturgi. Jeg lytter ærbødig, og finner trøst.

Martin Pollack

A note in the FAZ this week made me conscious of the legacy of the Austrian historian and Polonist Martin Pollack. I was struck by the way he predicted, a decade ago, much of today’s European political reality, an outcome almost bound to follow, he maintained, if we stayed hellbent on making decisions based on an ‘unhappy mixture of arrogance and ignorance’. I read Christoph Ransmayr’s noble obituary of Pollack from January this year. Then two long drives gave me time to listen to some of Pollack’s lectures and public conversations: a fascinating one on the ‘Myth of Galicia‘; another on living with ‘The Long Shadow of a Sinister Past‘; a lively interview with Markus Müller-Schinwald; and a podium discussion with Timothy Snyder on the ‘East-Europeanisation of politics‘ (the last two items are in German). Though my acquaintance is recent, this exposure to Pollacks’ learned, humane perspective makes me appreciate what Paul Ingendaay meant when he wrote: ‘We’d have a pressing need for courage like his here and now.’

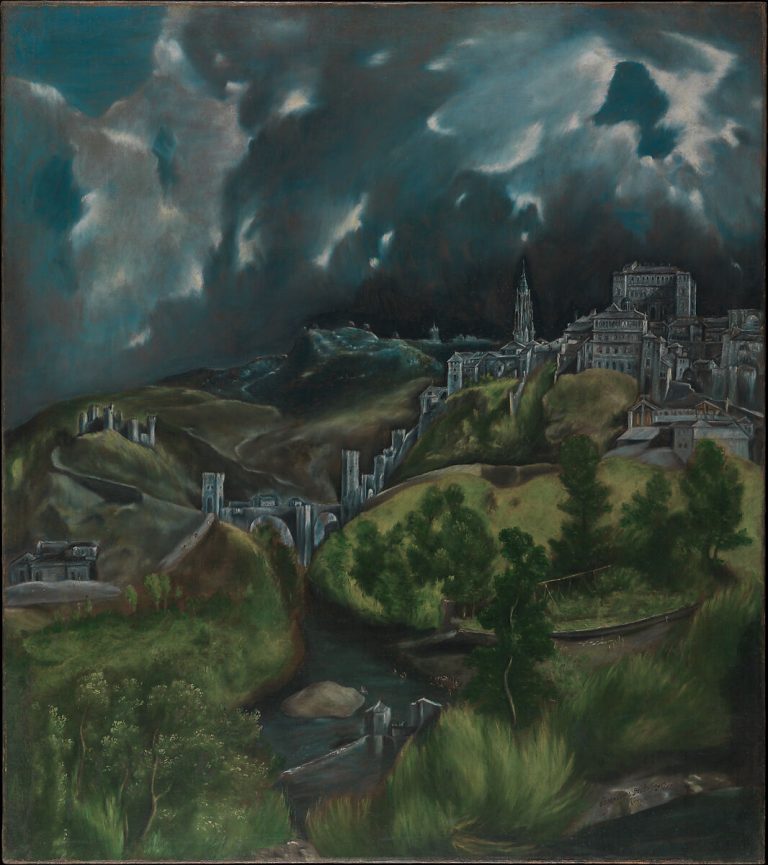

Light Tills the Ground

El Greco’s View of Toledo has occupied me for quite a while, but I had seen it only in reproductions and on the internet. When last week I found myself, amazed, in the Met’s Fifth Avenue gallery before the actual canvas, I was stirred by the sheer power of it. Rilke saw the painting in Paris in 1908, and wrote to Rodin, whose secretary he was, describing how ‘splintered light tills the ground, turning it over, tearing into it and bringing up here and there pale green meadows behind the trees standing like insomniacs.’ It is wonderful that a work of art can, in this way, enable a community of response, enabling a peal of thunder that resounded over a Spanish countryside well over 400 years ago to give us goosebumps still.

Nugax

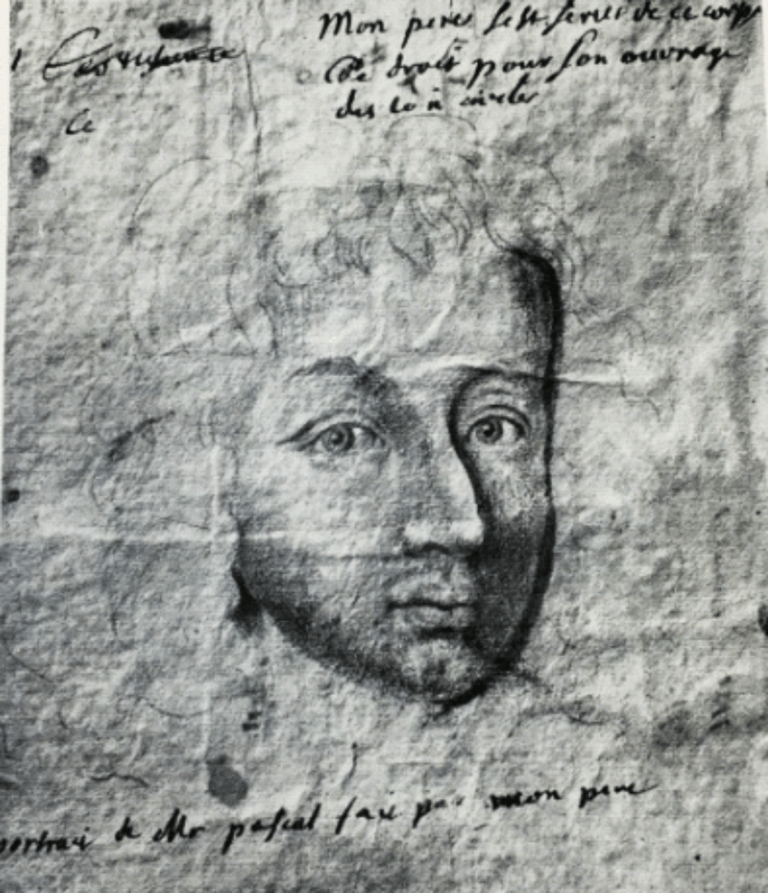

Til Laudes i dag gir Kirken oss følgende utrop blant forbønnene: ‘Libera nos a malo nosque a fascinatione nugacitatis, quae bona obscurat, defende’. Setningen lar seg ikke lett oversette i hele sin pregnante kraft. Uttrykket ‘fascinatio nugacitatis’ kommer fra Vulgata-oversettelsen av Visdommens Bok, vers 12, kapittel 4 og har satt dypt preg på kristen bevissthet. På latin henviser «nugax» til noe trivielt og frivolt, eller til en frivol, triviell person. «Nugacitas» står for overfladisk tidsfordriv, en tendens som trekker oss bort fra alvor og målrettet innsats; som distraherer oss og får oss til å tenke at, nå, ingenting er så viktig; som forfører oss med underholdning og mulighet for umiddelbar tilfredsstillelse. Tendensen synes uskyldig, men i virkeligheten tjener den til, slik bønnen uttrykker det å, «overskygge det gode». Den roter til selve kategoriene godt og ondt. Så er den til syvende og sist heller ingen kilde til egentlig glede. «Nugacitas» er vår tids popkultur i et nøtteskall. Det er modig motkulturelt å be om å «beskyttes» mot den. Vi kalles til å sette vesentlige grenser. I et Pascal-fragment står det: «Fascinatio nugacitatis. For at lidenskapen ikke skal skade oss, bør vi handle som om vi kun hadde åtte dager igjen å leve.»

Freedom & Constraint

Offering Mass this morning, I was struck by the offertory prayer: ‘Be pleased, O Lord, we pray, with these oblations you receive from our hands, and, even when our wills are defiant, constrain them mercifully to turn to you.’ We recoil at the notion of anything, even divine agency, constraining our will; yet at the same time we ascertain that our spontaneous will does not necessarily serve our thriving. It can even happen that our will is divided against itself: ‘For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do’ (Romans 7.19). To ask God, the supremely Beloved, freely to constrain my will is to step outside the constraints of subjective unfreedom manifest in dictates of unfree, perhaps disordered preference, thereby to learn to love.

Order

In an article in The New Statesman this week Bruno Maçães reflects on the tendency in global politics to break structures down for destruction’s sake or, at most, to engender a tabula rasa for an imagined brave new world. What has happened to the principle of order in public discourse? ‘The idea of order’, he writes, ‘is a valuable one because it expands the mind. It forces us to step outside our own perspective, to look for balance and impartiality in a broader horizon where others have their place too.’ The trouble is that now ‘there seems to be no order worth preserving’. The assumption is widespread. It accounts for much anxiety, much anger. Even the most casual grasp of history shows that such an assumption cannot sustain society. It fragments, disorders. Catholic theology has the valuable concept of tranquillitas ordinis enunciating an aspiration to concord, the communion of intelligent hearts. It’s time to blow the dust off it, not just to propound it but to demonstrate it in micro-societies. Deafened as we are by inflated rhetoric, stunned by virtual fantasy, the real renewal of the polis will, based on sound concepts, be experiential.