Life Illumined

Synodality and Holiness

The essay below corresponds to a conference given this spring. It was published on 21 October on the website of First Things.

The text in PDF can be found here. A French version is available here. The text is also available in Italian and Polish.

In April this year I was privileged to address the General Chapter of the Benedictine Congregation of Solesmes. The assembly had asked me to reflect on the theme of ‘Synodality and Holiness’. I was perplexed at first. I had not thought of synodality in terms of holiness. True, we have recently heard the word used such a lot that we have come to think it has a bearing on everything; though in terms of an essential bond it is usually associated, not with an eschatological ideal but with a process of government linked to the motions of an ecclesiastical body, Vatican II.

Observers have argued that the now ongoing synod’s vision is like the overflowing of the Council’s cup. Cardinal Grech, the synod’s secretary general, has been more cautious, conceding that the word ‘synodality’ is absent from the Council’s documents but submitting it arises therefrom in the manner of a dream. If we struggle to configure the dream, it may be because ‘synodality’ is protean, prone, as another authority has pointed out, to be ‘dynamic, not static’, like the sea.

Observers have argued that the now ongoing synod’s vision is like the overflowing of the Council’s cup. Cardinal Grech, the synod’s secretary general, has been more cautious, conceding that the word ‘synodality’ is absent from the Council’s documents but submitting it arises therefrom in the manner of a dream. If we struggle to configure the dream, it may be because ‘synodality’ is protean, prone, as another authority has pointed out, to be ‘dynamic, not static’, like the sea.

Not all are born sailors. Some face the waves anxiously, seeking a fixed point, a constellation in the sky to steer by. For such, the category of holiness is helpful. The commission I received this spring taught me that. It led me to adjust my perspective and perceive the sought-for bridge uniting the synod’s work now to the Council’s vision and teaching. For as far as holiness is concerned, the Council was wonderfully explicit. The fifth chapter of the great constitution on the Church, Lumen Gentium, set holiness as the note by which all the Church’s instruments must ever be tuned. Christ, we are reminded, ‘loved the Church as His bride, delivering Himself up for her. He did this that He might sanctify her’ (n. 39). Only in so far as we consent to be sanctified in Christ will we correspond to our Christian purpose and foster ‘a more human manner of living’ in this world (n. 40), whose descent into inhumanity terrifies. The Council insists that each state of life has a holiness proper to it. Pursuit of it will call for sacrifice. The witness of the martyrs is evoked. The summing-up is almost incredibly bold: ‘All the faithful of Christ are invited to strive for the holiness and perfection of their own proper state. Indeed they have an obligation to so strive.’ From this obligation a practical consequence is drawn: ‘Let all then have care that they guide aright their own deepest sentiments of soul’ (n. 42).

Deep sentiments of soul are now at stake. It seems timely to weigh them against this summons. We might do so by reviewing the motif of synodality first in the Old Testament, then in the New in order to ask how best we might apply it to our lives — how it might lead us together to the goal we seek: holiness.

Synodality in the Old Testament

Let us first clarify terminology. The etymology of ‘synodos’ has been rehearsed ad nauseam: ‘hodos’ is Greek for ‘a way’; ‘syn’ means ‘with’. A ‘synodos’ is a way pursued in fellowship, a journey shared. A journey presupposes a goal. The ascetic tradition is scathing about pilgrims who walk round and round. St Benedict regards the type of such circularity, the gyrovague, as the ultimate loser. For Biblically minded people, the notion of the ‘way’ evokes strong associations. We know from St Luke that the Church in apostolic times was called ‘The Way’ (Acts 9.2). Christ declared himself to be ‘the Way’ (John 14.6). That is the Way to follow. Its goal is clear. In the high-priestly prayer Christ prayed: ‘Father, I desire that those also, whom you have given me, may be with me where I am, to see my glory’ (John 17.24). To be with the Father’s beloved Son, the Image of God (Col 1.15) in whom we were created (cf. Genesis 1.27) now and for ever has been the human race’s call since the beginning.

A degree of synodality is implicit in God’s act of creation: ‘Let us make man in our image, according to our likeness’ (Genesis 1.26). To realise our iconic potential, becoming like God is the purpose of our being. Such movement is not accomplished in isolation. After the creation of Eve, man and woman were to be, in consecrated union, ‘one flesh’ (Genesis 2.24), oriented towards one another in complementarity. The dynamic is applicable more broadly. It is meeting the gaze of another that reveals me to myself, enabling me to understand and develop myself in communion.

The account of original communion is followed by the story of the fall. It reveals a darker side of synodality:

When the woman saw that the tree was good for food, that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate; and she also gave some to her husband, and he ate. Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked (Genesis 3.6-7).

Collusion resulted in the death of innocence. The other, familiarly reassuring just a moment ago, was reduced to a stranger, at once attractive and fearful.

Scripture qualifies the action provoking the fall as ‘sin’, a death-dealing loss of direction. One result of sin is the more or less deliberate will to entice others into my forlornness, which seems to me now, owing to a numbing of consciousness, as reality itself, my milieu vital. The thought of remaining alone in it is unbearable. A call to walk synodally away from a freely owned dependence on God is made explicit in the project of Babel. People said to each other: ‘Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth’ (Genesis 11.3-4). Their desire was to maintain a coherent assembly, to create a societal model attractive enough to unite all humankind. Their criteria were self-destructive, although they did not see it. The project was sabotaged by the Lord himself.

The vocation of Abraham, our father in faith, was synodal. Having heard God’s call, he took his wife Sarai, his brother’s son Lot […], the persons whom they had acquired in Haran’, and set forth to go to the land of Canaan (Genesis 12.5). At first it went well enough. As long as the journey’s destination is remote, susceptible of idealisation, synodality does not pose major challenges; travellers envisage the nature of the trip as they please. When the journey’s end approaches, when questions arise of dividing territory, tensions arise. The possessions of Abram and Lot were such that ‘the land could not support both of them living together’ (Genesis 13.5f.). They split. ‘Separate yourself from me’, said Abraham, ‘if you take the left hand, then I will take the right’ (Genesis 13.9). This story helps us relinquish simplistic notions of synodality. If one does not have the same finality in mind, the same image of a paradise to restore, a centrifugal force will make itself felt. Unity, ever vulnerable, will then be liable to break.

This tendency is at work in the story of Israel’s exodus from Egypt, which structures our preparation for Easter each year. Moses, Aaron, Miriam, and a handful of initiates, prepared by providence, had a lucid view of the reasons why they must get out of Egypt and find the promised land. The synodal assembly at large was more pragmatically minded. These folks desired a better quality of life, diversion, recognition. Such aspirations are legitimate, but insufficient to preserve unity in forward movement for a variegated crowd, a ‘vulgus promiscuum innumerabile’, to cite Jerome’s memorable rendering of Exodus 12.38, spelling the beginning of an account of multiple conflicts, dissensions, and break-aways.

Anyone with the time and inclination might pursue this reading of the synodal motif through the historical and prophetic writings. What we are left with is an Old Testament perspective on synodality which cannot be called cynical, for each page of Scripture is redolent with hope; it is simply realistic. This is useful. To proceed together towards holiness, towards an encounter with the Holy One, we must follow a royal road that is sometimes narrow.

Synodality in the New Testament

The Gospel passage most commonly referred to in synodal texts is the story of the wanderers to Emmaus. It is sublime, offering ever new layers of meaning. We might equally well perform a reading in a synodal key of the call to Mary or the Apostles, to Mary Magdalene or Paul. Thereby we could learn much about what it means to walk in companionship with the Son of God. It is his presence, after all, that makes up the criterion for synodal authenticity.

I am drawn to a more discreet synodal narrative in the New Testament, the testimony of a man who came to faith almost despite himself, who followed Jesus at a distance, though without losing sight of him; who stayed faithful to the end, though remaining in the shadow. I speak of Nicodemus. Nicodemus, ‘a ruler of the Jews’, turns up in the third chapter of the Fourth Gospel. ‘He came to Jesus by night’ (3.2), an approach emblematic of our times, whose faith often has a nocturnal character. Nicodemus poses pondered questions. He is reflective, serious, seeking real answers to real problems. In this respect, too, he represents the present mood.

Nicodemus wants to be heard, yet is able to listen attentively. Here we touch a raw nerve. On the whole we are not very good, now, at listening. We are collectively afflicted with logorrhoea, prone to inattention and selective deafness, also within the Church, in synodal discourse. Everyone has something to say. Everyone expects to be heard. But are we willing to listen to what the Lord says, then to heed firm in faith, strong in resolve, freely and trustfully?

Jesus’s conversation with Nicodemus touches God’s self-revelation. It tells us that it is possible to live a life saturated by God’s Spirit. It speaks of God’s philanthropy, which leads him to empty himself that we might live, an example we are bidden to imitate; it posits eternal life as the one worthy goal of man’s pilgrimage on earth; it stresses the freedom we possess to choose between life and death, light and darkness, a freedom for which we must one day answer before God. On that day we must give an account in person for choices we have made, even though they may have been swayed by synodal energies.

Having heard and received Jesus’s teaching, Nicodemus recedes back into the night. He embodies a splendid text in Isaiah: ‘My soul yearns for you in the night; even by means of my spirit, in my innards, I seek you; for when your judgements are resplendent on earth, the dwellers in the world learn justice’ (26.9, following the New Vulgate). Nicodemus is one who truly waits for God’s judgement to shine on earth.

We encounter him again at a meeting of officials during which high priests and pharisees seek to eliminate Jesus. Nicodemus protests, ‘Does our law judge a man without first giving him a hearing and learning what he does?’ (7.51). To walk with Jesus and create about him synodal fellowship, we must weigh his words and deeds, seeking their significance and grounding ourselves in his salvific epiphany without giving in to passing views, prejudices, and expectations.

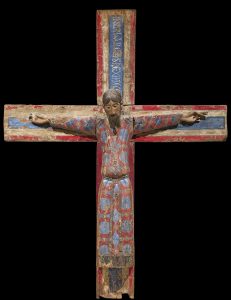

Nicodemus’s third appearance in the Gospel is by Jesus’s tomb. Clearly he has followed the crucifixion at a distance. Now, when the disciples grieve over their Friend, he draws close, bringing ‘a mixture of myrrh and aloes, weighing about a hundred pounds’ (19.39). The Christians of the Middle Ages meditated at length on this scene. They saw in Nicodemus one who had pierced the mystery of the Passion, who had embraced it, and could therefore communicate it to others. A tradition arose that attributed works of art, moving representations of the Crucified, to Nicodemus. He was considered the creator of both the Holy Face of Lucca and the Batlló Crucifix. It is significant, surely, that our medieval forbears found him apt to be a sculptor, master of a tactile art, forming what he had seen with his eyes, touched with his hands (cf. 1 John 1.1). Without needing to debate the veracity of such ascription, we can recognise in it perennial symbolic validity and value.

Nicodemus is, I submit, an example for us who strive synodally to be true disciples and seekers after holiness. Why? He stays away from facile polemics and theatrical gestures. Still he follows the Lord wherever he goes. When he is needed he offers his service and volunteers his friendship to the community. He shows us what it means to be faithful in the darkness of Good Friday. Contemplating the crucified, entombed Christ, he had wisdom to recognise in desolation something sublime, a glorious, divine revelation. Thus he became an authoritative witness to the Crucified’s victory. Truly, this is an attitude the Church needs now.

And We?

To be a Christian, a Catholic today is challenging. There’s no two ways about it. Looking around we can be tempted to exclaim with a Psalm: ‘O God, the heathen have come into your inheritance; they have defiled your holy temple; they have laid Jerusalem in ruins’ (Psalm 79.1). To be a heathen is to be one who does not truly believe, however much he may carry trappings of faith. We live with the wounds of abuse, regarding which we all hoped they would be a matter concerning just our neighbours, not us. Our communities are shrinking. The agonising question, ‘How long?’, presents itself in settings that within living memory seemed unshakable. Trust has been betrayed. Prophets of desolation abound. The spirit of division, rife in society, raises its ugly head in the Church, too. There is a peculiar sadness abroad.

And yet, this is the day — and night — that the Lord has made and entrusted to us that it may be for us a time of salvation. How can we, in such a time, live out our vocation to holiness?

First by bearing, at one with the Lamb of God, our part of the weight of the sin of the world, a sin not reducible simply to ungodly acts. This sin stands no less for a worldly lostness chaotically voicing pain that tends towards despair, often lacking an object and for that reason being especially redoubtable. The Lamb of God ‘takes away the sins of the world’ not by snapping his fingers like a magician, but by bearing it. We are called to live as members of his Body.

The faithful who, with Nicodemus, are summoned to prefer light to darkness at all costs (cf. John 3.18-21) must be ready to bear synodally the weight of night which is the portion of many people now. This presupposes readiness to stay within that night, praying there, loving and serving there, slowly recognising there, be it at a distance, the light no darkness can overcome (John 1.5).

Reading and rereading the sources of monasticism, the great Lives (of Antony, Hypatios and others) that, before Rules were written, indicated the path to life, I am struck by the recurrence of the topos of compassion, understood concretely as willingness to ‘suffer with’. This is surely a key aspect of the synodal experience: participation, by means of patience, in the redemptive Passion of Christ. This is a time to reflect on what Paul speaks of in a hushed voice to the Colossians: ‘in my flesh I complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the Church’ (1.24). It is profoundly significant that the Second Vatican Council, expounding the universal call to holiness, referred explicitly to martyrdom:

Since Jesus, the Son of God, manifested His charity by laying down His life for us, so too no one has greater love than he who lays down his life for Christ and His brothers. From the earliest times, then, some Christians have been called upon — and some will always be called upon — to give the supreme testimony of this love to all men, but especially to persecutors. The Church, then, considers martyrdom as an exceptional gift and as the fullest proof of love. By martyrdom a disciple is transformed into an image of his Master by freely accepting death for the salvation of the world — as well as his conformity to Christ in the shedding of his blood. Though few are presented such an opportunity, nevertheless all must be prepared to confess Christ before men. They must be prepared to make this profession of faith even in the midst of persecutions, which will never be lacking to the Church, in following the way of the cross (Lumen Gentium, n. 42).

‘All must be prepared’. Without melodrama, with Christian sobriety charged with good sense, we must own that this call touches us. Likewise we must believe that the messy unpredictability marking any vulgus promiscuum making its way in synodal progress, following the path of the commandments (cf. the end of the Prologue to St Benedict’s Rule), secretly realises a divine melody. I take immense comfort in the confession of a Benedictine nun of the past century, Sister Elisabeth Paule Labat, who intimately knew the vicissitudes and traumas of life while remaining rooted in the freeing, transforming grace of the Cross. She articulated her mature insight thus:

[Growing in wisdom] man will perceive the history of this world in whose battle he is still engaged as an immense symphony resolving one dissonance by another until the intonation of the perfect major chord of the final cadence at the end of time. Every being, every thing contributes to the unity of that intelligible composition, which can only be heard from within: sin, death, sorrow, repentance, innocence, prayer, the most discreet and the most exalted joys of faith, hope, and love; an infinity of themes, human and divine, meet, flee, and are intertwined before finally melting into one according to a master plan which is nothing other than the will of the Father, pursuing through all things the infallible realisation of its designs.

Holiness is an essential category, not a label attached as a seal to impeccable conduct. Holiness is that which is essentially divine, categorically unlike any quality, even the loveliest, extant in creation. The way to holiness is illumined by uncreated light. We must be changed to perceive it. Our eyes, hearts, and senses must be opened; we must step outside our limitations, into a dimension of truth that is of God.

Synodality leading in this direction, configuring us to our crucified and risen Lord, is life-giving, redolent with the sweet perfume of Christ Jesus (2 Corinthians 2.15). Synodality, meanwhile, that encloses us in limited desires and predictions, reducing the purpose of God to our measure, must be treated with great caution.

The Batlló Crucifix or ‘Batlló Majesty’: Stat crux dum volvitur orbis.