Arkiv, Samtaler

Samtale med Luke Coppen

Da jeg samtalte med Luke Coppen om fastetiden i fjor, nevnte jeg Johannes Klimakos traktat Himmelstigen. I år ville han fordype emnet. Nedenfor finner du en utveksling offentliggjort på The Pillar. Du finner flere samtaler med Luke Coppen her (oktober 2023), her (Den stille Uke 2023), her (julen 2022), og her (sommeren 2022).

* * *

In your garage, you may have an object that has been used by human beings for more than 10,000 years. Yours is likely made of aluminum or fiberglass, rather than rope or wood as in the distant past. When you take out your ladder, what do you see? A tool for changing light bulbs, perhaps, or cleaning out your gutter. More than 1,400 years ago, a monk named John looked at a ladder and saw in it an image of the spiritual life. He was so taken by the similarities that he wrote a treatise for his fellow monks known today as “The Ladder of Divine Ascent.” The spiritual ladder he envisioned had 30 rungs. He called the first step “renunciation of the world” and the second “detachment.” He described how each step up took you closer to union with God. Christians have been reading this work ever since it was completed, in around 600 A.D. It has been described as one of the most influential Christian texts after the Bible. In the monastic tradition, it’s common to read “The Ladder” during Lent. But the book is not exclusively for monks. As Bishop Erik Varden, a Trappist monk who leads Norway’s Territorial Prelature of Trondheim, explained in an email interview with The Pillar, it contains something for everyone.

– In the 21st century, there seems to be an entire sector of the publishing industry devoted to ladders. There are titles like “How to get onto the property ladder,” “Climbing the corporate ladder with speed,” and “The magic ladder to success.” This is nothing new: around 600 A.D., a monk called John Climacus wrote a treatise using the image of ascending a ladder. Why is the ladder a good image for spiritual life?

Because it’s got its feet on the ground. A ladder not well grounded is of no use. It slides when you start to ascend. In Christian vocabulary, the image of the ladder has Biblical roots. Climacus presupposes the ladder Jacob saw in a dream when he set out from his father’s house after buying his brother’s birthright for a mess of lentils. You remember the story: Jacob spent the night at Bethel and dreamt ‘that there was a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven; and behold, the angels of God were ascending and descending on it!’ (Genesis 28.12). The ladder speaks of the possibility that human endeavour might ascend heavenward; that grace might descend to earth. Christ refers to this passage when he calls Nathanael (John 1.51). What to Jacob was aspiration has, in Christ, become personal truth. In him, heaven and earth are one. We, being incorporated into his mystical Body, the Church, partake of this truth. Basically, the ladder tells the story of our call to become, dust as we are, ‘partakers of divine nature’ (2 Peter 1.4).

– Kallistos Ware once wrote: “With the exception of the Bible and the service books, there is no work in Eastern Christendom that has been studied, copied and translated more than The Ladder of Divine Ascent by St. John Climacus.”

Why has the treatise had such a profound impact on Eastern Christianity?

It is at once a work of profound theology and an extremely practical manual. It tells us what to do to start climbing. Its pedagogy works. It is a reliable guide. Generation upon generation testifies to the Ladder’s practicability and efficacy. I’d add that this is true not only for the East. The Ladder has had a profound impact on Western Christianity, too. Abbot de Rancé, the seventeenth-century reformer of La Trappe (from which Trappist monks and monasteries derive their name) translated this work into French — for when he was not busy writing pamphlets against the intellectual work of monks, he was a formidable Greek scholar — and when in 1686 he extended the abbey church at La Trappe he dedicated a chapel to St John Climacus. That says a lot about his debt of gratitude; and about the imprint left by this work on the Trappist Cistercian heritage to this day.

– The Ladder has also shaped Western Christian spirituality. You pointed out last year that in the monastic tradition, Lent is the traditional time to reread the treatise.

Why is it good Lenten reading?

If you permit me to answer monastically, I’d refer to the Rule of St Benedict. Lent, says St Benedict, is a time to repair shortcoming of other times. It’s a time to remind ourselves where we are, where we are going, to pull our sock up. It is also a time during which we are reminded, through the liturgy, of the need to pass through the desert in order to reach the promised land. Israel’s Exodus provides the paradigm for our Lenten journey. The Ladder gives us, if you like, a road map by which to direct our steps.

– The Ladder is very methodical. It describes a ladder with 30 rungs, each of which marks a progression in the spiritual life. Each “step” up the ladder is discussed in short, numbered paragraphs. The style is quite pithy.

What advice would you give to a lay person reading it for the first time? After all, it was written for monks — not, say, for a mother with three children under the age of five.

Said mother may well live more ascetically than your average monk, so would have a good head-start. My first advice is this: don’t get too hung up on tiny details, but get a sense of the general movement proposed in each step. Take Step Two, on detachment, for example. A mother with children may not get too excited by cited minutiae of monastic observance, but would, like any Christian, be given food for thought by the counsel: ‘Let us pay close attention to ourselves so that we are not deceived into thinking that we are following the strait and narrow way when in actual fact we are keeping to the wide and broad way.’ It’s a perspective that invites us to look at ourselves and aks: What are the lights I’m steering by? Which path am I on? Is the motor that drives me self-satisfaction, or am I driven by the love of God and a disinterested love of others? In this instance: Do I see my children as means to my fulfilment or do I pour myself out that they might live and become what God calls them to be, a call that necessarily exceeds my prognosis? I’m rhapsodising, but you get my point. There is something here for everyone.

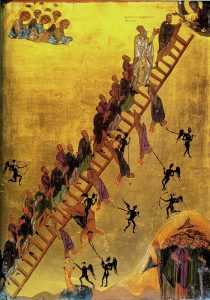

– There is a celebrated icon inspired by The Ladder at St. Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt. It shows monks clambering up a ladder while silhouetted demons yank some poor souls off the rungs.

Do you think the icon captures what John Climacus was getting at?

It certainly renders the fact much distracts us from the pursuit of a radically Christian purpose. Single-mindedness and concentration are called for. This image can create the impression that Climacus, and the tradition he represents, was obsessed with demons. That is not the case. The monastic tradition is unanimous in stressing that the demons are powerless before the grace conferred by Christ’s cross. St Anthony the Great said to his disciples: The devil is like a caged bird. He only has destructive, distracting potential if we lend him our attention and heed his suggestions. That’s the message of the icon. If I determinedly shake off the temptation that weighs me down, it falls away: it has no wings with which to fly. But if I grant it a grip, it will let me feel the weight of its own heaviness. That accumulated weight might be sufficient to pull me away from the ladder altogether, to cause me to crash-land back on the ground from which I set out. Further, let’s not forget Climacus’s point: ‘A proud monk [or man, or woman] needs no demon. He has turned into one, an enemy to himself’ (Step 23).

– The treatise begins with a definition of Christian life: “The Christian is the one who imitates Christ in thought, word and deed, as far as is possible for human beings, believing rightly and blamelessly in the Holy Trinity” (Step 1, 4).

What do you think is notable about that definition?

Not least the connection between right belief and fruitful conduct. It matters to have a true conception of the faith. Faith is not a matter for improvisation or subjective preference. There is a tendency in our time to think that it doesn’t so much matter what I believe about God as long as I aspire to be decent, neighbourly and kind, as if that were all Christianity amounted to in the final analysis. By all means, it is fine to be decent, neighbourly and kind. But most of us find that there are limits to our decency, neighbourliness and kindness. Once sacrifices are called for, we invoke principles of reason and proportion. We say, ‘Now, really, I can’t go any further; it would be irresponsible’. Only a clear notion of a God who is communion, an eternal movement of fullness and self-emptying; who for the sake of despairing mankind left divine prerogatives behind, stooping to a level of contingency; who on the cross assumed all darkness, carrying it bodily — only such a notion gives the measure of the Christian. And so, in order to imitate Christ, we need, first, to know and understand who Christ is. To put it differently: moral integrity presupposes intellectual integrity. Which isn’t to say we’ve all to be great scholars. But we need to know what we’re about as Christians, and why.

– A lot of us begin climbing ladders tentatively, worrying that we might fall off. John recommends the opposite approach: he says we should start out energetically (Step 1, 11).

Why is it important to really throw ourselves into the spiritual life, especially at the start?

I’d be cautious about advising people to throw themselves into the climbing of a ladder. More important than enthusiasm is clear resolve. Resolve may take a while to form. Think of the parable in the Gospel of the man who set out to build a tower. Before I start climbing the ladder, I need to sit down and consider it for a while. I need to gauge the relative distance of the rungs and exercise my joints, to make sure my knees are up to it. I can benefit from seeing others climb, to learn from both their expertise and their mistakes. I need to test myself and ask: Do I really want this? Am I drawn to reach the top? It is good to make an energetic start in the spiritual life, but my beginning has to be sustained by perseverance. Perseverance concerns the configuration of the will. Once my will is mobilised and my desire is well ordered, energy will ensue. Then I’m ready to start climbing.

– Step 1 in The Ladder is renunciation. Step 2 is detachment. Step 3 is the less familiar concept of “exile.”

What might “exile” mean for, say, someone who has just retired and wants to deepen their spiritual life?

I think someone like that is well equipped to see the sense of exile, having lost, perhaps, a sense of significance, finding him or herself with much leisure but little finality, feeling lonely and exposed at a time when the body shows signs of fatigue and one faces death’s inevitability. Though there’s another side to the coin. In Climacus’s Greek, the word for ‘exile’ is xeniteia. It can also sustain the translation ‘pilgrimage’. Bear that in mind. A pilgrimage goes somewhere. I’m invited, urged to ask, what is my goal, now? I’m challenged to follow that goal single-mindedly. Climacus says in this chapter, ‘It is impossible to look at the sky with one eye and at the earth with another’. That outlook can be applied to various circumstances. It’s of special pertinence for men and women on their way up a ladder.

– While The Ladder sounds very lofty, there is a striking realism throughout. For example, John writes: “To admire the labors of the saints is good; to emulate them wins salvation; but to wish suddenly to imitate their life in every point is unreasonable and impossible” (Step 4, 42).

Do you think John’s realism might be helpful for, say, a young man or woman today who is discerning their vocation?

It’s certainly a summons to self-knowledge, which St Teresa of Avila, almost a millennium after Climacus, insisted is ‘the bread to be eaten with every dish’. But let this not become a pretext for sitting on the fence. These days, a mystique of discernment is cultivated to such an extent that to ‘be in discernment’ has become a vocation in its own right. Such an attitude takes no one anywhere. Literally. Being a realist is no excuse for not making up one’s mind and for not constructing one’s Christian life and call in an optic of service and worship.

– John is big on perseverance. He writes: “Do not be surprised that you fall every day; do not give up, but stand your ground courageously” (Step 5, 30).

What might it mean to “stand our ground courageously” this Lent?

It brings us back to the very image of the ladder, I think. Where have I planted it? On good, solid terrain, perhaps with a rock to keep its base from moving? Or in a dungheap whose foundation is slippery? To stand one’s ground is also to have the courage to keep getting up — to resist the temptation to think, ‘Oh, since I have fallen already, I may as well just wallow in the mud for a bit.’ At a later point in the Ladder Climacus says: ‘Don’t dawdle!’ (Step 12). That’s good advice.

– John also wants readers to experience what he calls “angerlessness.” He writes: “If the Holy Spirit is peace of soul … and if anger is disturbance of heart … then nothing so prevents his presence within us as anger” (Step 8, 14).

Why does anger make ascending the ladder so treacherous?

The Fathers tend to regard anger as the mother of all passions. The point is astute. A lot of us, I’d say, carry loads of anger of which we are not aware. Why not? Because the sorts of things that inspire anger tend to be the sorts of things that humiliate and hurt us, so we suppress remembrance of them. As moderns we are alert to the reality of ‘passive aggression’. We see it in others. Do we look for it in ourselves? Are we prepared to own and clear out the angry spaces within us, the spaces where we count ourselves victims — consciously or unconsciously — and so feel ourselves absolved from standards of decency, entitled to get our own back? Anger is structurally self-centred. It imprisons me in myself. It blinds me to my neighbour. It inoculates me against the desire for God. It makes me disinclined to put even a single toe on the bottom rung of a heavenward ladder. A good resolution this Lent might be to examine ourselves honestly in search of traces of hidden anger, with the resolve to clear it out, the way Israel cleared out the least fragment of old leaven (Exodus 12.15), to let the new bread, the bread of life, rise fresh and unhindered for nourishment, a bread to be shared.

– Why do you think that “love” is the subject of the final, 30th step, rather than an earlier one?

Love is there at the beginning, too. ‘Christ’s love urges us’ (2 Cor 5.14) — thank God; otherwise we’d be stuck. But the love born in our own hearts, the love that casts out fear, takes time to grow and bear fruit; its growth is organic, like any growth. Not for nothing is the Gospel full of parables from agriculture. The love we’re talking about here is no sentiment. This love is participation in the life of Christ, an intimation of God’s own life. Many people get discouraged because they do not feel they have love for God. Discouragement leads them to dig holes instead of climbing ladders. So Climacus comes to our help. He shows us how to live in order that love may grow, on the principle that ‘the soul is moulded by the doings of the body’. Love represents Christian purpose. Determination sprung from freedom is the ladder’s foundation; love is its end — at once the fruit of patient effort and gracious gift. By climbing we learn, little by little, to pray. I love what Climacus says in Step 28: ‘Prayer is by nature a dialogue and a union of man with God. Its effect is to hold the world together.’ Given the state our world is in, nothing could be more important.

12th century icon of Ladder of Divine Ascent, now in Saint Catherine’s Monastery on Sinai, showing monks, led by John Climacus, in a movement of deliberate ascent. Wikimedia.