Arkiv, Samtaler

Samtale med Luke Coppen

Du finner en nettversjon av intervjuet her.

Last year, around 19 million Americans — one in every 14 U.S. adults — were expected to spend Christmas alone. Do you have any advice for someone who has to spend Christmas by themselves this year?

A solitary Christmas can be a blessing. A lot of people feel distracted at Christmas, torn between appointments, shopping and chores, anxiously trying to generate a much mythicised Christmas ‘mood’. To embrace the prospect of Christmas alone offers a chance to celebrate the feast contemplatively. In the last days of Advent, the liturgy lets us pray, again and again, ‘Come, Lord Jesus!’ But who is there to really welcome him if all have their minds mainly on turkey stuffing? The solitary might, then, turn what seems like an indictment into a preferential option, offering their home and their heart as an attentive, well-prepared inn in  which the Word will be tenderly welcomed. That does not mean they can’t have a nice meal, listen to carols on the radio, and perhaps go for a walk around the block after Mass, praying for the neighbours, rejoicing with those who rejoice, calling mercy down upon those in distress — for there will be those, too. This last point makes me want to consider a wholly other perspective on your question. Do I, in fact, ‘have’ to spend Christmas on my own? Is there not somebody I could ask, or whom I could visit? It’s not set in stone that we have to celebrate Christmas with relatives. If we have none, or if we are estranged from those we have, that does not mean we are on our own in the world. Why not invite somebody else’s solitude into mine — and perhaps discover a communion of unexpected joy? The Word made flesh can be present in that scenario, too.

which the Word will be tenderly welcomed. That does not mean they can’t have a nice meal, listen to carols on the radio, and perhaps go for a walk around the block after Mass, praying for the neighbours, rejoicing with those who rejoice, calling mercy down upon those in distress — for there will be those, too. This last point makes me want to consider a wholly other perspective on your question. Do I, in fact, ‘have’ to spend Christmas on my own? Is there not somebody I could ask, or whom I could visit? It’s not set in stone that we have to celebrate Christmas with relatives. If we have none, or if we are estranged from those we have, that does not mean we are on our own in the world. Why not invite somebody else’s solitude into mine — and perhaps discover a communion of unexpected joy? The Word made flesh can be present in that scenario, too.

What about for someone who cannot even leave the house this Christmas?

I’d advise them to be monastic about it, which is to say: devise a timetable! If I go around telling myself, ‘I’ll be all alone for all of Christmas Eve and Christmas Day’, those 36 hours will seem interminable. If instead I say to myself: ‘Right! I’ll start with Carols from Kings at 4. I’ll get supper ready. I’ll ring Aunt Susan, then spend half an hour pondering the Christmas Gospel. I’ll read a Christmas story by Selma Lagerlöf; then watch Mass online.’ Et cetera. You get the idea. What matters is not to frame some dictatorial scheme, but to fill the day with purpose, all the while asking: is there perhaps something I can do for someone else? At Christmas we all tend to regress into childhood, expecting others to fill our stockings, to shower us with affection, to put a hand around our shoulder. There is something lovely in such aspirations; there can also be something pathetic. Do you remember the account of Christmas 1886 in Thérèse of Lisieux’s Story of a Soul? It describes the incident which she, that incomparable Doctor of the Church, would later refer to as her ‘conversion’. The family had just returned from Midnight Mass. It was time for presents, for rehearsed procedures of anticipated indulgence. Thérèse was thirteen. She was just popping upstairs when she overheard her father, by then a weary widower, say: ‘All this childish stuff! I hope it will be the last year we have to do it.’ She felt a pang of sadness, as if she, afflicted by nervousness, had brusquely been thrown out of her own childhood. Her sister Céline, aware of what was going on, expected a tearful scene. But the scene didn’t happen. Thérèse realised, with preternatural acuteness, that she was not at the centre of events; that the time had come for her, not to be indulged, but to comfort. She swallowed her sadness, not as if it were poison, but as if it were the last morsel of a dish she had really done digesting, then joined the family radiant, creating happiness for others, making her father laugh. She later wrote: ‘On this night of grace, the third period of my life began—the most beautiful of all, the one most filled with heavenly favours. […] Our Lord Himself took the net, cast it, and drew it out full of fishes. He made me a fisher of men. Love and a spirit of self-forgetfulness took possession of me, and from that time I was perfectly happy.’ The Lord might invite us into such a grace this Christmas, if we let him.

Is being alone bad for your spiritual health? After all, many saints seemed to prize solitude.

The English language makes the very useful semantic distinction between loneliness and solitude. Loneliness is a negative condition, one in which I feel deprived of company I want, perhaps ardently yearn for. Solitude meanwhile is a state of aloneness enabling me to touch the depths of who I am in order, potentially, there to discover a resonance of the Word in whose image I was made, who desires to become flesh in me, drawing me into the peaceful life of the blessed Trinity, which is communion. A degree of solitude is indispensable for spiritual life. It can be cultivated even in company. Even as it is possible to be in a crowd, at a loud party, and feel painfully lonely. To grow up as human beings and as Christians, whatever our state of life, we must cultivate a capacity for solitude. As we mature, we may find it has transformative potential. Can an apparently enforced loneliness become an elective solitude? Potentially, yes. If we let go of bitterness; if we refuse to imprison ourselves in self-pity; if we say ‘Yes!’ to what is and call out to God from there, rather than thinking we must attain some other place, or state of mind, first.

Is there anything the Church can do — at Christmas and other times — to reach the growing number of people who live alone?

Keep eyes and ears open; notice who is homebound, then ring them — or visit; organise gatherings and meals to which all are invited; develop good online offers of streamed services, nourishing reading material, and links to good, formative resources. It is basically a matter of turning round from asking, ‘What do I wish for and need this Christmas?’, to asking, ‘Where am I needed?’

There is no shortage of ascetic manuals offering precise instructions on how to pray and mortify our senses. When it comes to Christmas, the Church encourages us to feast for 12 days. What does it really mean to feast? And is it possible to do it alone?

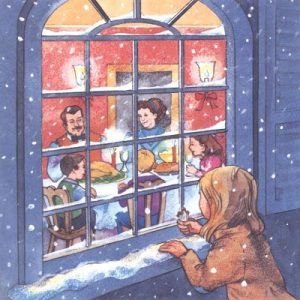

When the Church exhorts us to rejoice, she is not telling us just to pin on a smile and to have huge, indigestible meals. She affirms that the deepest truth of the human being is joy. At Christmas she proclaims that God entered our nature, took on our flesh, in order to clear the way for that joy, enabling it to circulate freely, removing obstacles. To learn to feast well is to ask, ‘What in my life stands in the way of joy?’ Then to see what can be done about it. Joy is of its nature ecstatic, which is to say, quite simply, that it brings us out of ourselves. That revolution can be accomplished in any circumstance. The Christmas Gospel is full of people who think they are alone, then realise they’re not, that Emmanuel, God-with-us, is there, with them: the shepherds in the field, Mary and Joseph, Anna in the Temple — all those dear people featured on our Christmas cards. What they stand for is no fairytale. They stand for the reliability of divine promises. If we abandon the expectation of predetermined sentiment and instead give ourselves up to those promises, the promises of a faithful God who by definition makes everything new, Christmas could be for us, as it once was for Thérèse, the beginning of a new era, an era of freedom, of love’s entry into our lives.