Arkiv, Samtaler

Samtale med Luke Coppen

The online version of this interview is here.

What does the Church expect of us in Holy Week? One thing is clear: it wants us to take part in the great services of the Easter Triduum, the three days of Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday. But what about the times in between?

Although the Triduum can feel like a frantic rush between church and home, and back again, sometimes there are quiet moments. What’s the best way to fill them? One possible answer is the rosary: the ancient and ingenious Marian prayer using 59 stringed beads. As you pray, you meditate on events in the life of Christ, including those commemorated in the Holy Triduum.

How can the rosary lead us deeper into the events of Holy Week? The Pillar asked Bishop Erik Varden, a spiritual writer, Trappist monk, and Prelate of Trondheim in Norway.

The mysteries of the rosary cover many of the events commemorated in Holy Week. Does that make it a particularly apt prayer for this week?

The rosary is an apt prayer for every day. It lets us interiorise the mystery of faith while lodging it in the historical account of the Gospels. Personally, I have always been partial to the custom — of German origin, I think — of articulating the series of specific mysteries within the Hail Mary: ‘…and blessed is the fruit of thy womb Jesus, who sweated blood…’, et cetera. Such litanic repetition lets the sequence of Christ’s life and saving work penetrate our consciousness peacefully and powerfully.

In what ways might praying the rosary during Holy Week serve as a bridge between personal devotion and the communal liturgies of the Triduum?

Ideally the twain should overlap in any case. What the liturgy does with singular force during Holy Week is to integrate us personally into the celebration. It engages our sensibility and agency by means, for example, of the procession with branches on Palm Sunday, the washing of feet on Maundy Thursday, the individual veneration of the cross on Good Friday, the lighting of tapers during the Easter Vigil.

By these simple but efficacious means the Church, a sterling pedagogue, lets personal and communal spheres overlap; indeed she allows us to express in public intensely intimate realities, as when each of us, in full public view, kneels to kiss the wood of the cross without in any way feeling we are victims of a violation of privacy; on the contrary, it is strangely consoling to find fellowship in vulnerability. The rite’s predictability provides the right balance of palpable communion and respectful distance.

By these simple but efficacious means the Church, a sterling pedagogue, lets personal and communal spheres overlap; indeed she allows us to express in public intensely intimate realities, as when each of us, in full public view, kneels to kiss the wood of the cross without in any way feeling we are victims of a violation of privacy; on the contrary, it is strangely consoling to find fellowship in vulnerability. The rite’s predictability provides the right balance of palpable communion and respectful distance.

This is a dimension of society that otherwise has been entirely lost to us. But are we not hungry for it? The rosary wonderfully infuses these Paschal encounters with unsentimental, maternal sweetness.

The rosary is, of course, a Marian prayer. Why is it helpful to meditate on Mary’s role in the events of Holy Week through the rosary’s mysteries?

Is the rosary in fact a ‘Marian prayer’? I’d say yes and no. Yes, in the sense that the Blessed Virgin is the person to whom our entreaty is addressed; no, insofar as the thrust of Christian prayer is always christocentric. The first part of the Hail Mary is itself a mosaic of scriptural passages. It draws us into the annunciation of Christ’s incarnation, the enthralling meeting of the ambassador of Transcendence with the young woman who represents the hurting density of ‘all flesh’.

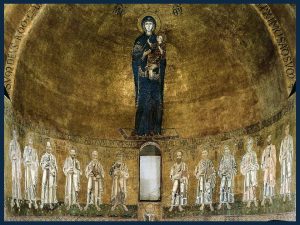

Speaking of mosaics — think of the wonderful representations of the Virgin in the apse of many ancient basilicas, most famously in Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia. Are these works manifestations of ‘Marian devotion’? No, we couldn’t really say that. The terms would have seemed meaningless, I expect, to believers of the ninth century. The Virgin is given pride of place in the sanctuary, above the altar on which the Sacred Mysteries are enacted, not as an added extra to enliven piety, but as the Guarantor of the Mysteries’ embodied realism. Even as Christ our Lord was incarnate in the Virgin’s flesh at a given, datable moment of history, so he is really present in the Eucharistic sacrifice.

Wherever, whenever the Virgin is present in Scripture, art, and devotion, it is as Hodegetria, that is, as one who ‘shows the way’, who points towards Christ and indicates where we can find him, saying, ‘Do whatever he tells you’. This dynamic strikes us when we pray the rosary during Holy Week. It enables us to consider the passion through the prism of the incarnation, drawing the whole of Christ’s life into unified perception. Our ancestors in the faith had a keener sense of this connectedness than we today, who for all sorts of cultural and digital reasons are much better at categorisation than at synthesis. I am sure you will have seen medieval statues or paintings of the Pietà, Mary holding Jesus after the deposition from the cross, in which there is explicit reference to the nativity motif of Mother-and-Child. I am always lost for words before such images. They express a truth, an internal coherence, that is vital but exceeds the expressive potential of mere words. The rosary can help us make, and make sense of, such connections.

points towards Christ and indicates where we can find him, saying, ‘Do whatever he tells you’. This dynamic strikes us when we pray the rosary during Holy Week. It enables us to consider the passion through the prism of the incarnation, drawing the whole of Christ’s life into unified perception. Our ancestors in the faith had a keener sense of this connectedness than we today, who for all sorts of cultural and digital reasons are much better at categorisation than at synthesis. I am sure you will have seen medieval statues or paintings of the Pietà, Mary holding Jesus after the deposition from the cross, in which there is explicit reference to the nativity motif of Mother-and-Child. I am always lost for words before such images. They express a truth, an internal coherence, that is vital but exceeds the expressive potential of mere words. The rosary can help us make, and make sense of, such connections.

Would you recommend combining praying the rosary with other personal devotions in Holy Week, for example, the recitation of the seven penitential psalms?

By all means. Above all, though, I would counsel people to focus on the missal and breviary, letting themselves be drawn into the mighty current of the Church’s prayer, oriented through centuries to irrigate the earth and our dried-up hearts. In the Holy Week Masses, in the offices of Tenebrae, in the Commemoration of the Passion and the Paschal Vigil, we have at our disposal a magnificent mystagogy, a careful introduction into the saving mystery that is at once sublime and wholly accessible. Why not let ourselves be taken by the hand by the Church, our Mother? That way we shall appreciate the Marian dimension of our faith, not just as ‘devotion’, but as the atmosphere within which, as a Christians, we live and move and have our being, where, with Mary, Christ’s Mother and ours, we learn to own and express our deepest grief and our most exultant joy, carried by a well-founded hope that is at once intelligent and visceral.