Arkiv

Desert Fathers 48

You can find this episode in video format here – a dedicated page – and pick it up in audio wherever you listen to podcasts. On YouTube, the full range of episodes can be found here.

Abba Ammoes asked [Abba Poemen] about certain impure thoughts that the human heart conceives and about fruitless desires. Abba Poemen said to him: ‘Shall the axe be vaunted over him who hews with it?’ You, likewise: do not give [your thoughts] a hand and take no pleasure in them, and they will be ineffectual. Abba Isaiah asked the same question. Abba Poemen said: ‘If somebody abandons a chest full of clothes, they will decay over time. When it comes to thoughts, the same process applies: as long as we do not put them into concrete action they will over time decay and be gone.

The battle of the heart of which we have heard Antony speak plays out to a large extent in the mind. It is unhelpful to envisage the two as categorically distinct. We are inclined nowadays to think that thinking goes on in our brain whereas our heart is the seat of feelings. At the same time, we recognise the truth of what Christ says: ‘out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaks’. The heart has, Biblically speaking, intellective faculties. Affectivity and intelligence are intertwined. It follows that if we are serious about desiring a pure heart, we must first of all labour to purify our minds. But what a cesspit our mind sometimes seems to be! We dream, then, of fumigating it, seeking an instant remedy that might eliminate all noxious content.

Poemen tells us that this is an illusory dream. Once we have allowed a thought or desire into our heart and mind, it settles and makes itself comfortable. We are not built as computers: there is no ‘delete’ function that will, when a button is pressed, get rid of undesirable content. Poemen’s message to both enquirers, Isaiah and Ammoes, is the same. He assures them impure thoughts can be excised, but only over time, through a process of slow starvation. Patience is called for, and endurance.

The saying about the axe, which Poemen cites, is from Isaiah, part of an oracle about causality. A tool is only effective when someone wields it. It is not an autonomous agent. Isaiah invokes a range of examples. His point is ethical, even political: human institutions may not glory in themselves when used as instruments for purposes intended by God. The Lord enables and moves them then, none other.

We are asked, similarly, to consider where our bad thoughts come from, then to cut them off at the source. If we do, they will sooner or later lose their power and leave us in peace. For a thought or desire has no more autonomy than any old tool we may have lying about in our garden shed. Thoughts can impersonate autonomy. The Enemy of good may manipulate them in such a way. But it is by callous deceit. As long as we do not nurture the poisoned content of our mind, it will wither. We shall need to build up sticking-power to sit tight while this process takes place.

To speak concretely, we may take as an example a battle many people fight: that of pornographic addiction. A cynical industry engenders this unfreedom by playing on registers that touch our deepest desires and darkest fears, all within a miasma of vulnerability. A person may be seduced by pornographic propositions for a while, thinking perhaps they are coming to terms with sexual frustration, telling themselves this is freeing. Then the moment comes when they see that content they have watched does not stay in the ether, but lodges itself in the mind, conditioning relationships, disabling innocence.

Such a person may wake up desperate one day and think, ‘For God’s sake, get this stuff out of my head!’, only to find that no such immediate option exists. The temptation will be great to burrow more deeply into the source of impurity, to give in to its proffered promise of comfort and satisfaction. One may see through the lie of it, perhaps, yet feel there is nowhere else to go, all the while being plagued by an ever more all-encompassing unhappiness and shame.

To such a one Poemen says: despair not!

He assures him or her there is a way out of captivity. He gives them a twofold piece of advice. First they must turn off the tap of unhealthy stimuli, seeking whatever help they need to do so. Then they must take responsibility for mental, affective baggage acquired. They must learn to say, in the first person: These impulses do live in me, for I have let them in, but now I stop; when a thought or image from my hoard comes to me, I will not pick up and fondle it, but give it to the Lord with a prayer for mercy: ‘Lord, this thought was mine, but now I offer it to you; it will no longer have power over me; create a new heart in me; teach me to love beautifully’. Over time this procedure can work transformation. Of course, it applies to other addictive thought-processes, too, like wounds to our pride.

The Fathers tell of an elder who lamented in his cell: ‘On account of a single word, all this gone!’ Asked to explain, he said: ‘I know 14 books of the Bible by heart, yet a single complaint against me obsessed me for the whole of today’s liturgy!’ It can be upsetting to realise what scorpions lurk in my heart. After all, I would like it to be a pure temple to the Lord. But once I know the blighters are there, I can take action, putting a tumbler over them to curtail their movement, making sure they are not fed.

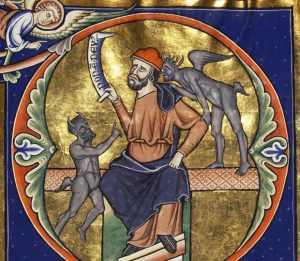

Initial D: The Fool with Two Demons (detail) in a psalter, illuminations by the Master of the Ingeborg Psalter, after 1205. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment bound between pasteboard covered with brown calf, each leaf 12 3/16 x 8 5/8 in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 66, fol. 56.