Arkiv, Høytlesning

Desert Fathers 24

Abba Antony said: I think the body possesses a physical movement that is mixed up with it, though it does not work except with the consent of the soul. There is another [kind of] movement which comes from nurturing and heating up the body with food and drink, on account of which hot-bloodedness moves the body to act. That is why the apostle said: ‘Do not get drunk with wine, for that is debauchery’. And the Lord in the Gospel gives the disciples this commandment: ‘Be on guard so that your hearts are not weighed down with dissipation and drunkenness’. There is, though, yet another movement affecting those who fight [the ascetic battle]. It is born of the wiles and envy of the demons. You need to know, then, that there are three kinds of bodily movement: one physical; one sprung from indiscriminate eating and drinking; and one worked by the demons.

It was customary for a long time to consider St Antony an unlettered bumpkin. This was partly because he was known for his extravagant temptations. Scholars who were sons of the Enlightenment took it for granted that, had Antony read more books and been smarter, he would have been armed against trials of this kind — a position that betrays, really, great (and potentially culpable) naivety on their part.

A detail in Athanasius’s life nurtured this misconception. We read that as a child Antony ‘was raised by his parents, knowing nothing besides them and life at home’; then that, growing older, ‘he did not continue learning his letters, wishing to stand apart from the normal activities of children.’ What the text says is that Antony did not wish to be conditioned by prevailing pagan culture. He chose to develop an independently Christian mind. Early modern readers, however, assumed he had simply dropped out of school. Great was the perplexity, then, when a cache of letters attributed to Antony was unearthed. These texts betrayed a high degree of intellectual culture. A number of people assumed they were spurious; others more creatively asked if it might not be the case instead that the prevailing image of Antony was false? This last lot was proven right. Hardly anyone now doubts the authenticity of the letters.

The saying before us corroborates the account of Antony as a man of subtle thought. Introducing the section of the Apothegmata devoted to lust, it sets the scene, as it were, for disquisitions to follow. The distinctions Antony draws are extremely helpful. Had they been better known, better taught in seminaries, noviciates and marriage preparation courses, much perplexity and pain might have been avoided.

For is it not often the case that when things go awry in people’s sexual and affective lives, nature is blamed? One hears people say, ‘My body’s natural urge was too strong!’ or ‘This is just who I am!’ Sometimes this may be so; but not always.

Antony sets out from a clear affirmation: the body’s ‘movement’, its erotic impulse, is fundamentally neutral, untouched by stains of immorality. To be human, a man or woman, is to have physical urges. In themselves they are good. They can become a source of happiness, expressions of love, if directed well by the discerning reason of our intellectual soul. According to our true nature, made in the image of God to be like him, body and soul are not at odds. The pursuit of chastity is about reconquering their fruitful complementarity. Pressed for definitions, the Fathers are unlikely to have called this first kind of urge porneia. It is just physical eros.

The second kind is more ambiguous. The body, no longer working ‘naturally’, is in imbalance on account of overindulgence. Rich food and immoderate drinking stimulate physical passion. Anyone who over time has fasted or practised abstinence will know this interconnectedness from experience as appeasement. There is a chance, therefore, that the body’s lustful urges are not merely ‘natural’ but fuelled by gluttony, acquiring that vice’s characteristics, no longer seeking communion in love but rather private satisfaction, stimuli to feed on. To start combating impure lust, I must begin by examining what, and how, I eat and drink, to equilibrate appetite.

The third kind of lust is demonic. The sayings abound in accounts of devils assailing sorely-tried ascetics like swarming flies. Let us not too quickly dismiss these tableaux as superstition. They do presuppose the reality of the ‘hater of good’. At the same time they are instances of imaged speech that convey realities hard to fathom in words. What they boil down to is this: a realisation that we human beings are, in the realm of our sexuality wounded by sin, prone to impulses that may be irrational, perverse, and destructive. With these there can be no dialogue. They must be driven out by prayer, compunction, and the revelation of the heart. How to recognise them? They induce deep sadness, even despair.

The Fathers do not say that that all lust fits under this heading; but neither do they call all desire pure. At once dispassionately lucid and shrewd, they teach us to discern. That is why they could give counsels both sublime and practical. They would elevate the tempted person’s mind towards God’s love. At the same time they would say things like these: ‘Never take more than three cups; and do not hang around in places where you have sinned against God.’

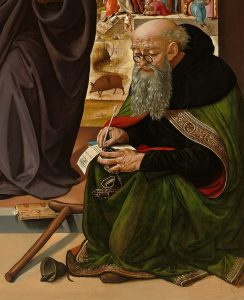

St Antony will not have looked anything like this, but it’s an engaging motif all the same, displaying him as a writer, smart spectacles and all. Piero di Cosimo, Visitazione con Sant’Antonio abate (1490), now in the National Gallery of Arts in Washington.