Arkiv, Høytlesning

Desert Fathers 26

You can find this episode in video format here – a dedicated page – and pick it up in audio wherever you listen to podcasts. On YouTube, the full range of episodes can be found here.

Two brothers went off to the market to sell their wares. Having parted company, one of them fell into lust. When the other brother returned, that one said to him: ‘Brother, let’s go back to our cell!’ But he said: ‘I’m not coming’. The other besought him saying, ‘Why, brother?’ He said: ‘When you left me, I fell into lust.’ His brother, wanting to gain him, said: ‘The same thing happened to me, too, when I left you. But let us go! Let us forcefully repent, and God will forgive us.’ They went and told the elders what had happened. The elders prescribed how they should do penance. And the one did penance for the other, as if he himself has sinned. When God, after a few days, saw what pains he took for love’s sake, he revealed to one of the elders that he who had sinned had been forgiven on account of the great love of him who had not sinned. This is what it is to give one’s life for one’s brother.

The fathers ate their bread in the sweat of their brow. To live, they had largely to be self-sufficient. They made saleable stuff, the production of which was compatible with their contemplative purpose: mats or ropes. Having built up a stock, they sold it. Trips into the city were called for. In this way the interface between desert and ‘world’ remained vibrant. It could lead to salutary encounters. At the same time it posed challenges. Alexandria did not provide the ascetic safeguards of Scetis. A monk out of his cell had to rely on his virtue being interiorised. It was not always.

This situation-bound story provides a parable into which we can easily read ourselves. Most of us conduct our daily lives within predictable parameters. We learn to negotiate these. Familiar boundaries steer our behaviour and choices. We know where temptations are, and occasions of sin, so take prudent precautions. Life seems safe enough. But what happens when we find ourselves in unfamiliar, unbounded places: alone on a trip, say, away from our community or family; sauntering unrecognised through a metropolitan red-light district; or just finding ourselves before an unguarded, unobserved computer? Is our virtue then reliable and firm?

We do not know exactly how the monk we read about ‘fell into lust’. Did he have an illicit encounter? If so, was he the seducer or did he succumb to seduction? Did he pursue porneia through some kind of pornography? Or was the sin of ‘lust’ a sudden conflagration in his mind that led to impure thoughts, and possibly deeds?

By not being specific, the apophthegmata exercise their pedagogy. These stories are not just historical exemplars; they are intended as mirrors of conscience. To work as such their applicability must be at once pointed and broad. The key thing to note is diabolical hopelessness induced in the brother. Looking at himself through the prism of what just happened, he thinks: ‘Good God! There is no way back!’ He is convinced that all his devout endeavours have been futile and insincere — else, how could he so easily have fallen? The thought of going back to the setting of his consecration, where once he pronounced a Yes! he had wished to be final, is unbearable. Not only does he feel, now, unworthy of his cell and the companionship of his faithful brother; the cell and the brother would be for him a reproach he reckons he could not endure. His mind is made up. He thinks: ‘I have rolled in mud: the mud is now where I belong’. Believing himself defined by his sin, he is sure he is beyond redemption’s reach.

This is where his companion comes to the rescue. This other fellow, returning from errands cheerfully and innocently run, sees his brother downcast. He instantly knows: something serious has happened. He owns at least to a degree a charism prized by the fathers: cardiognosis, the ability to read another’s heart in charity. He sees a humiliated man hurt in his convictions who thinks himself beyond repair, bound to remain an object of disdain. He knows: the only ointment that will work in this case is compassion — compassion not just by way of saying, ‘My poor friend, what an awful thing; still, pull yourself together’; no, compassion in the sense of taking on himself what the other carries, much as it was said about Antony: ‘He did suffer with the suffering’.

The enlightened monk knows it could be fatal, now, to look down on his brother. So he places himself at his level. Saying, ‘I did the same!’, he relieves him of thinking himself an outcast. Thus he inflames courage to repent, to start again. He assures his brother of God’s power and will to save. We may object: But did he not thereby tell a lie? Not if we adopt the fathers’ mindset. Antony said: ‘Our life and our death is with our neighbour.’ My brother’s burden is mine to help bear and repair. That is what life in the mystical body is like. In the intimate reality of monastic fellowship, or that of a married couple, this dynamic truly takes on flesh. Combined with the guilty brother’s confession and repentance, the pure monk’s vicarious penance was effective. ‘This is what it is to give one’s life for one’s brother’, a universal command. We read in Scripture that God ‘for our sake made him to be sin who knew no sin, that in him we might become the righteousness of God.’ That work carries on in the Church. It does not cancel justice, but infuses it with charity, letting the sweet aroma of Christ ascend as from a censer from the burnt coals of our life.

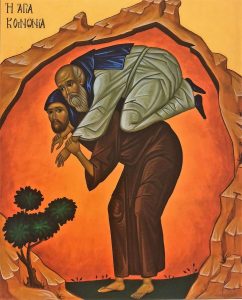

Koinonia – fraternal communion. An icon from the monastery of Bose.