Arkiv, Høytlesning

Desert Fathers 32

You can find this episode in video format here – a dedicated page – and pick it up in audio wherever you listen to podcasts. On YouTube, the full range of episodes can be found here.

Saint Gregory said: If, when you proposed to give yourself up to philosophy, you thought you would encounter no hardship, your induction will have been unphilosophical. Blame attaches to your formators. If you are prepared for hardship but find you do not meet it, it is a grace; if you meet it, you must endure it patiently. Else you will not be true to your purpose.

To us, the word ‘philosophy’ designates an academic discipline often perceived as being so abstruse that it seems to have no bearing on practical life. The enclosure of philosophy within a narrow framework of technical terms and assumptions was a notable feature of intellectual life in the twentieth century. As a result many women and men take it for granted, now, that philosophy has nothing to say to them. ‘Philosophical’ has come to spell ‘useless’. A friend once told me of a conversation he had overheard on a British train. A lady relayed at length to a friend some business that had caused her great hardship. The friend, having taken all this in, replied: ‘My dear, you have to be philosophical: don’t think about it!’ It is a telling quip.

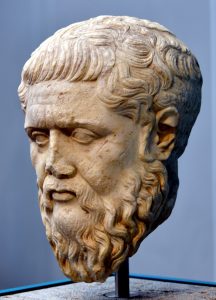

The ancients envisaged ‘philosophy’ differently. Plato introduces the term towards the end of the Phaedrus. Socrates and Phaedrus have spent an afternoon trying to find a term that may suitably apply to a variety of intellectual endeavours: one that describes what Lysias and the rhetoricians are up to while also defining the work of Homer and the poets, Solon and the makers of laws. How, asks Phaedrus, might one word describe these three exemplary professions? Socrates answers that to call each ‘wise’ [sofos] would be to go too far: ‘that epithet’, he says, ‘is proper only to a god. A name that would fit […] better, and have more seemliness, would be “lover of wisdom” [philosophos], or something similar.’ Phaedrus is satisfied. Socrates shows himself a worthy philosopher when, before the two friends take leave of one another, he makes this prayer to the gods: ‘Grant that I may become fair within, and that such outward things as I have may not war against the spirit within me.’

You and I may have trouble thinking of speech-makers or lawyers, or writers of poetry, who would merit the title ‘philosopher’. That is our loss. The search for wisdom ought to be the basis of public and cultural life, and no one will seek her with integrity and determination unless he loves her. By Plato’s lights, philosophy spells disinterested self-transcendence in articulate pursuit of an objective good.

It was with this definition in mind that monastic life came to be known, quite early on, as philosophy. True, few monks were producers of texts; but all sought to make of their lives a statement — a lovely statement — worthy of the gracious truth of God’s gift in Christ. They strove to live logically, one with the saving, divinising Logos.

Naturally, there is also a more specific aspect to the association of monks with philosophy. For readers of the Greek Old Testament, the Sophia of philosophia was a personal presence, none other than the figure of Wisdom that emerges, sublime and familiar, in the last books of the Jewish Scriptures as a divine agent ad extra, the means by which an eternal, limitless, immaterial God engages concretely with creation. In the eighth chapter of the book of Proverbs, Sophia speaks. Putting her nature into words, she explains the role attributed to her in the creation and sustenance of all that exists in the universe as we know it: ‘I was beside [God], like a master workman; and I was daily his delight, rejoicing before him always, rejoicing in his inhabited world and delighting in the sons of men’. For all their austerities, the Desert Fathers aspired to know this delightful Wisdom. They were no strangers to her joy although they contemplated it in through the prism of Christ’s Paschal sacrifice.

The early Church saw the Old Testament’s Wisdom as a type of the Word by which all things came to be, the Word made flesh in Mary’s womb. That connection finds mature expression in the first of the O Antiphons we sing during the last days of Advent, when, on 17 December, we invoke Christ as ‘Wisdom proceeding from the mouth of the Most High’, then ask him: ‘Come and teach us the way of prudence.’

For a Christian minded to live and think coherently, philosophy is structurally christocentric, for Christ is the measure of reality. In the light of what he did for us, philosophy is, too, what Edith Stein, a sophisticated intellect, called a ‘science of the cross’. Philosophy will yield its deepest secrets only when illumined by a self-sacrificing love at once notional and embodied. That is what Abba Gregory hints at. He traces a trajectory monks must follow if they are serious about reaching, through the folly of the cross, the wisdom from on high, ‘peaceable, gentle, open to reason, full of mercy and good fruits, without uncertainty or insincerity.’ A renewal of philosophy on these terms is overdue. We have a task before us.

Boethius wrote: ‘O strong of heart, go where the road/Of ancient honour climbs./Bow not your craven shoulders./Earth conquered gives the stars.’ Thus thought the humble desert dwellers, too, pressing on to enter where Jesus, our forerunner, has gone before.

Marble bust of Plato: a Roman copy (1st century AD) of an original (350-340 BC). Now in Altes Museum, Berlin. Wikimedia.