Arkiv, Høytlesning

Desert Fathers 41

You can find this episode in video format here – a dedicated page – and pick it up in audio wherever you listen to podcasts. On YouTube, the full range of episodes can be found here.

Temptation came upon a brother in the monastery of Abba Elit. Having been driven away from there, he went up to the mountain, to Abba Antony. The brother spent a while with him there. [Antony] then sent him back to the monastery from which he had gone out. But when [the brothers there] saw him, they drove him away again. So he returned to Abba Antony saying: ‘Father, they did now want to receive me.’ The elder then sent this message to them: ‘A ship suffered shipwreck at sea. It lost its cargo. With great labour it managed to save itself and reach land. You however: that which has been saved on land you wish to throw into the sea.’ When [the community] heard that it was Abba Antony who sent [the brother], they received him at once.

The Gospel tells the story of Peter coming to ask Jesus: ‘Lord, how often shall my brother sin against me, and I forgive him? As many as seven times?’ Jesus said to him, ‘I do not say to you seven times, but seventy times seven.’ To be a Christian is to make up one’s mind, once for all, ‘never to despair of God’s mercy’. That succinct phrase makes up the seventy-second and last of the ‘tools for good works’ in St Benedict’s Rule, the tool that holds in itself the potency of all the rest. We readily count on God’s mercy for ourselves. When we fall, we trust we shall be forgiven. Do we likewise forgive others? The imperative of pardon is repeatedly rehearsed in Christ’s teaching and in that of the Apostles.

By it, we shall be judged.

We must hear these particular Gospel words in context, though. The injunction to forgive ad infinitum occurs just after the bestowal on the Church of the power of the keys. By it the Lord outlines a process of reconciliation fixing certain terms. The scenario is that of a brother who has sinned and whose sin has been noticed. The question is: how does the Church engage with him? First, we are told,

go and tell him his fault, between you and him alone. If he listens to you, you have gained your brother. But if he does not listen, take one or two others along with you, that every word may be confirmed by the evidence of two or three witnesses. If he refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church; and if he refuses to listen even to the church, let him be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector.

To be pardoned we must be well disposed. Mercy is infinite, but not cheap. Sin is not final, but serious. Sacramental confession calls for contrition. Forgiveness is not distributed like samples from a candy store. A confessor is to be gracious. He is also to love the truth. Only on the basis of truth can fractured communion be restored.

Where this condition is lacking, where there is recalcitrance and hardness of heart, barriers may need to be put. Even as Christ envisages excommunication, the monastic rules provide for situations that seem, after repeated attempts at reparation, insoluble. The Rule of St Benedict contains a judicious penitential code setting out the procedures to be followed. Its motivation is explicitly medicinal: it seeks to bring the errant sinner back by helping him to amend. St Benedict enjoins immense patience. He urges the abbot to use every pastoral means to gain his brother back; but he does recognise that there may be times when the abbot, to preserve the health of the body of the community, may have to use ‘the knife of amputation’ and send a brother packing, ‘lest one diseased sheep contaminate the whole flock’.

We should not be too quick, therefore, to accuse Abba Elit and his brethren of cruelty to the errant monk. There may have been due process. It may have been impossible to keep him in the house. It is useless to speculate. We do not have further details. What we do know, and the only thing we need to know, is that the monk remained disposed to change. He did not give up or run away, but sought out one who might be able to heal and help. It says much about Antony that he was widely perceived as a refugium peccatorum. For all his exaltedness of life, he remained understanding of and receptive to those who struggled. Athansius speaks of him as a ‘physician given by God to Egypt’. Here we get some sense of what that meant.

We do not know what counsels Antony gave his visitor, what mortifications he imposed, how he breathed on the flame of his zeal. We are merely told that being in Antony’s company wrought such a change in the monk that he could envisage a return to where he had set out from. The community, though, said no. They saw him still for what he had been, for what he had done, unable to consider the possibility that he might have changed.

There is sadness in the report given to Antony: ‘Father, they did not want to receive me’. The monk may have come to doubt his ability to start our afresh. ‘Perhaps I cannot change? Am I doomed to remain forever in settled patterns of dysfunction and sin.’ Some of us will know such thoughts from experience. They are diabolical, inducing despair and causing us to doubt God’s omnipotence. If such temptation is galvanised by the curt judgement of others, it may seem insuperable. Hence the importance of Antony’s message to Elit and his monks. He urges them to have faith in God’s power to save and so to develop an ability to regard other people, including those who have caused hurt, with hope.

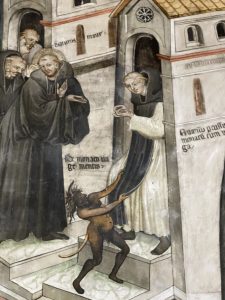

Mural from the church at Subiaco.