Arkiv, Høytlesning

Ørkenfedrene 7

Below is the text of the seventh episode in the series Desert Fathers in a Year. You can find it in video format here – a dedicated page – and pick it up in audio wherever you listen to podcasts.

A brother asked Abba Isaiah for a word. In answer, the elder said: If you wish to follow our Lord Jesus Christ, keep his word. And if you wish your part in the old Adam to be suspended with him, you must cut yourself off, until death, from those who would have you descend from the cross; and you must prepare yourself to bear contempt; and to appease the hearts of those who do you evil; and to humble yourself before those who seek to disenfranchise you; and to keep your mouth silent; and to judge no one in your heart.

As Christians we like to show to the world a cheerful face. We do not, after all, wish to put people off. We speak of joy, peace, and love, of kind, happy communities. We are right to do so. Our aspirations are true; so are the realities to which they refer. Virtues do not, though, simply fall from heaven. They are the fruit of labour, long and arduous work. The Kingdom’s new wine presupposes pressed grapes. From the twelfth century, we find in Christian art the motif of Christ treading the wine press. It is drawn from a synthesis of Biblical texts that speak of the vindication of God’s cause, of the harvest of righteousness, and of the promised land’s rich fruits. This image is an explicit type of Christ’s crucifixion. We may think of Jesus’s words to his disciples at the Last Supper: ‘I shall not drink again of this fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father’s kingdom.’ Having said this, he ‘went out to the Mount of Olives’, where Judas came in search of him to betray him.

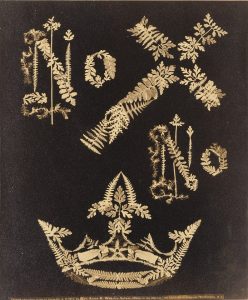

Few themes are as emphatically stated in the Gospel as this: ‘If any one would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me’. Even as Jesus stressed the need for his passion (‘The Son of man must suffer many things’) he stresses the need for ours. It was common once to find in devout people’s homes the saying, ‘No Cross, no Crown’, embroidered and framed on the mantle piece. There is truth in it. The so-called ‘prosperity gospel’ is make-believe, no basis for an integral Christian existence. Whoever wishes to belong to Christ, to abide in him, says St John, must ‘walk as he did’ through the passion and cross to the resurrection.

This is not to suggest that Christian life, to be genuine, must be miserable. It is to be realistic. Who knows a life unmarked by pain? Faith does not magic pain away; it lets us live painful things fruitfully, to make sense of them. To see sense is to soar out from from the snare of thinking ourselves hapless victims, so to become free.

Abba Isaiah exemplifies Christian realism. He does not beat about the bush. To a brother asking for a word to live by, he says first: Keep Christ’s word! We look to the Gospels for inspiration, comfort, and light; but do we consider them a task? Do we believe Christ’s commandments can in fact be kept? Or do we look on them with mental reserve, thinking: ‘Lovely ideas! But no one can be expected to accomplish them.’ Well, that is a mistake. We are expected to realise them, by determination and grace. Mary Ward, that visionary woman, used to say to her sisters: ‘Do your best, and God will help.’ Her words are a firm foundation from which to set out.

Note that Isaiah, like our Lord, appeals to the questioner’s desire. Twice he states, ‘If you wish’. Only then does he volunteer counsel. How solid is my Christian commitment? Do I wish to cast off the old Adam and put on the new? Perseverance in discipleship presupposes a sound motivation, to be revisited regularly in order that embers may be fanned into flames. There will be people around, those we love and those whose judgement we dread, who think what we are up to is folly. Isaiah advises us to cut ourselves off from them. His statement is fierce. The verb used is the same Jesus employs when he says, ‘If your foot causes you to stumble, cut it off’. We should not interpret this to mean that we must abandon our social circle when we start to live a focused Christian life. If relationships are toxic, distance may be called for for a while, that is true; still, Christians are called to draw others into discipleship by the witness of their lives, not to leave them in a ditch. The ‘cutting off’ applies first and foremost to dependencies. A Christian must be ready to swim against currents.

The cultivation of inner liberty is a life-long task. Isaiah makes that explicit. He goes on to specify what a share in Christ’s cross amounts to. He speaks of patience in adversity: learn to live by your own lights, not by others’ expectations, even when they ridicule your faithfulness. He speaks of silence: learn to process challenging things inwardly, with prayer, instead of spouting them in search of sympathy or admiration. Then he teaches us how to relate to others. This is the crux. The test of Christian authenticity is always relational. Rid yourself of the habit of judging others, therefore, for who are you to know what moves them or the change of which they are capable? Use humiliations as opportunities to grow in humility. Do not yield to bitterness. Then, spectacularly: seek peace for your adversaries. If we try to live on these terms, we shall know the cross’s rigour, which is love’s cost. We shall also catch glimpses of its glory, for our mortification is an engine of vitality, life in fullness.

Anna K. Weaver, No Cross, No Crown, 1874.

Albumen silver print of a photogram, now in the Smithsonian American Art Museum.