Arkiv, Høytlesning

Desert Fathers 9

Below is the text of the eighth episode in the series Desert Fathers in a Year. You can find it in video format here – a dedicated page – and pick it up in audio wherever you listen to podcasts. On YouTube, the full range of episodes can be found here.

It was revealed to Abba Antony in his desert that there was one who was his equal in the city. He was a doctor by profession and whatever he had beyond his needs he gave to the poor, and every day he sang the Sanctus with the angels.

For most of us, the single most important impediment to progress in the spiritual and moral life is this: we cling to the conviction that any such progress is sabotaged by our circumstances. We tell ourselves: ‘I cannot pray on account of such and such inescapable commitments; I cannot find silence within because of such and such distractions beyond my control; I cannot give alms because of my limited means, not to mention all my existing obligations to such and such people and causes.’ Each of us has his or her customised version of this universal rite of self-absolution.

We may experience pain on account of the circumstances to which we appeal. We may also be secretly comforted by them. As long as I can point to apparently objective factors that make it, so it seems, impossible for me to change my life or to pull up my socks my conscience stays easy. What is more, I can bask in the satisfying thought that if only things were different, I would of course make heroic choices, live a life of austerity and self-denial, perhaps even become a great saint.

From the beginning of institutional monastic life in the fourth century, we see a tendency in texts, songs, and poems, even in pictures, to idealise monks. Many of the sources come down to us present monks as people utterly apart, as if they were a categorisable subset of humanity, desert-dwelling Martians. By all means, many of the early monks were extraordinary. The patrimony documents credible examples of shining virtue, marvellous perseverance, fervent charity, and mystical graces. In addition, some of these men made life choices so plainly weird that they were beyond the reach of ordinary men — even though, it must be said, it was hardly any easier then than now to define what is ‘ordinary’. Think of the dendrites, who lived in trees, or the stylites, who spent their lives on pillars; think of the great fasters who lived for years on a few dry crusts; or of the staunch watchers who almost never slept. It is tempting to regard the monastic state as the prerogative of the fakir and so to think that the teachings and precepts emerging from the desert tradition have no relevance for anyone else. This is a considerable mistake.

It is a mistake for two reasons. Were monks to entertain it, they would yield to pride, a Luciferian delusion that obscures the purpose of conversion. Christians living in the world, meanwhile, would miss, by excessively idealising monks, the point that the monk is their brother and exemplar whose basic options are those of any disciple, simply magnified and amplified, to make the stakes clearer.

For these reasons we find that the early sources often stress that monks have no monopoly on perfection. They are no better than anyone else, simply more privileged. Often enough they may have much to learn from Christians living in the midst of the bustle of the city yet managing to keep their minds fixed on God, their hearts aflame with charity. This brief story told about Antony is a case in point. We are told that something ‘was revealed’ to Antony ‘in his desert’. Providence enabled him to see this something whether in a dream, in an illumination of the mind or in an intuition of the heart. God’s gentle grace nudges him and says: ‘Do not be seduced by your own spiritual progress or ascetic prowess. You still have a long way to go.’

What Antony saw was a man ‘who was his equal in the city’. This is striking. Antony spent the first part of his life moving further and further away from the haunts of men, seeking solitude. This was his call. Here he is reminded that his is but one of many paths. The man revealed to him, a doctor, embodied the very type of a professional who, in Antiquity as now, is constantly badgered by people who come to him with urgent ailments, some real, some imaginary. A doctor’s attention is constantly pulled in all directions at once. Yet this doctor kept great clarity of Christian purpose. How?

The story singles out two factors. First, ‘whatever he had beyond his needs he gave to the poor’. He was a man who refused to be seduced by his own sense of need, not yielding, as we easily do, to the thought: ‘I need this and that; and of everything I need more’. Instead he kept resolutely fixed on the necessities of others, giving alms in the name of Christ, who emptied himself that we might be filled. Secondly, the doctor daily ‘sang the Sanctus with the angels’. He was conscious of living in the presence of God, whose glory secretly suffuses the world, even hurting bodies of patients assembled in a doctor’s surgery. The man Antony saw made this consciousness explicit in a song of adoration, mindful of his call to become, like the angels, praise. By living on these terms, each of us can by God’s grace reach the heights of a desert saint.

Let us beware of coveting our neighbour’s call. Let us instead wholeheartedly consider, embrace, and be faithful to our own.

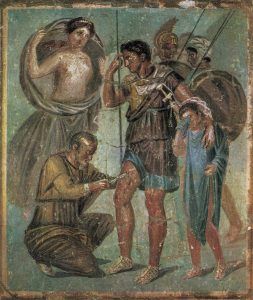

Fresco from a house in Pompeii showing Aeneas having a spear head removed from his thigh by the doctor Iapyx